Koca Mustafa Paşa Camii, Hazretı Cabır Camii

Koca Mustafa Paşa (died in 1512)

ca. 9th century

Description

Situated in the Ayvansaray quarter, on a hill descending to the southern shore of the Golden Horn, today’s Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii is largely identified as the former church of Sts. Peter and Mark or Sts. Cosman and Damian (Van Millingen 1912: 191; Aran, 1977: 247-53).

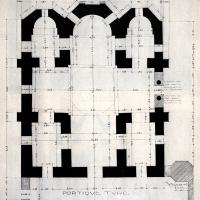

Based on the similarities in its cross-domed plan (15 m in width x 17.5 m in length) with Kalenderhane and Gul Camii, Van Millingen dated the structure back to the tenth century, as Jean Ebersolt (Van Millingen, 1912: 194, Ebersolt, 1920: 93-136). Nevertheless, two churches in question were later placed to the twelfth century through reliable archaeological evidence, which generated new discussions for redating Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii to the earlier periods (Müller-Wiener, 1977: 82; Mathews, 1995: 125). The eclectic nature of the church’s architecture with its three polygonal apses implies that the structure bears traces of the ninth and eleventh-centuries additions (Müller-Wiener, 1977: 83; Mathews, 1995: 128). Deprived of archaeological evidence, another possible dating goes as early as the mid-fifth century and associates the church with the shrine where the tunic of the Virgin was kept before it was restored in the Church of Theotokos of Blachernae (Mathews, 1995: 133; Müller-Wiener, 1977: 83).

Following the conversion of the church into a mosque around the year 1512, the mosque was named after the grand vizier of Beyazid II, Koca Mustafa Paşa (Müller-Wiener, 1977: 82). Necessary repairs for the church’s conversion included, the replacement of the cupola with a lower and windowless dome, the narthex with a porch, and certainly the addition of the sole minaret on the southwest corner (Mathews, 1995: 126).

VR Tour

Map Location

Bibliography

- Aran, Berge. “The Nunnery of the Anargyres and the Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque,” Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik 26 (1977): 247–53

- Ayvansarayi, Hüseyin bin Ismail. "Hadikat-Ül Cevami,” I 167 (Istanbul, 1894).

- Ebersolt, Jean. Mission archéologique de Constantinople (Paris, 1921): 22.

- Ebersolt, Jean. Les Églises de Constantinople (London, 1979):129-137.

- Janin, Raymond, La Géographie Ecclésiastique de L'empire Byzantin, Première Partie: Le siège de Constantinople et le patriarcat oecuménique, Les Églises et les monastères (Paris, 1969): 131-136: 402.

- Khatchatrian, Armen. Les Baptistères Paléochrétiens (Paris, 1962): 77.

- Mathews, Thomas.F.; E.J.W. Hawkins. “Notes on the Atik Mustafa Pasa Camii in Istanbul and Its Frescoes,” In Art and Architecture in Byzantium and Armenia: Liturgical and Exegetical Approaches, ed. by T.F. Mathews. (Brookfield: Variorum, 1995).

- Hawkins, E.J.W. 'Notes on the Atik Mustafa Pasa Camii in Istanbul and its frescoes', DOP 39 (1985): 125-34.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang. Bildlexikon zur Topograhie Istanbuls (Tübingen, 1977): 82-83.

- Papadopoulos, Jean.B. Le Palais et les églises des Blachernes (Athens, 1928): 162-165.

- Pulgher, David. Les Anciennes Églises Byzantines de Constantinople (Vienne, 1880): 28-29.

- Van Millingen, Alexander. Byzantine Churches in Constantinople (London: Variorum Reprints, 1974): 191-195.

- “Catalogue of Tiles from Sites in Constantinople and in Collections.” In A Lost Art Rediscovered: The Architectural Ceramics of Byzantium, edited by S.E.J.; Lauffenburger Gerstel, J.A. (Baltimore, 2001).