Myrelaion

Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos (920-44)

10th century

Description

Bodrum Camii, the former katholikon of the Myrelaion monastery is located in today’s Aksaray, on the steep slope leading down to the shore of the Sea of Marmara (Janin, 1969/GE: 351-54).

In so far as Byzantine chronicles are concerned, the earliest mention of the architectural remains located in Aksaray dates back to the eighth century, and is limited to the alternative names attributed to the monastic complex. Over years, the accounts of Theophanes the Confessor, George the Monk and John Scylitzes record that around the year 920, Romanus I Lecapenus has partly transformed his private residence that was constructed on a late antique rotunda into a monastery, and established the first burial chapel for the Lecapeni family (Naumann, 1966: 191-200; Striker, 1981: 3). His wife, Theodora who died in 922, before the completion of the complex is believed to be one of the first Lecapeni family members who was interred in the burial chapel (Striker 1981: 6). After the transfer of three sarcophagi that were brought from the Mamas monastery, Romanus was buried in the same chapel together with his two sons; Christophorus and Constantinus VII (Müller-Wiener, 1977: 103).

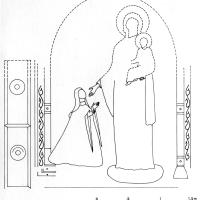

Over centuries, the monastic complex that functioned as a nunnery, has partly remained in ruins, especially after it has been seriously damaged following the devastating fire in 1203. In turn of the thirteenth century, the katholikon of the monastery was remodeled together with its substructure, which was transformed to a burial chapel for the Palaeologean family. As a part of the renovation project, the substructure has been partly filled with construction debris, and the entire floor was paved with large bricks, as revealed during the archaeological excavations (Striker, 1981: 11). In doing so, seven rectangular tombs, four on the south aisle, three in the bema on the eastern end were dug, and individually paved with stone slabs from all sides in order to imitate sarcophagi (Striker, 1981: 10). One of these three burials placed in the central east bay was singled out particularly by its spatial arrangement, as well as its fresco decoration of a female donor portrait in a trompe l’œil arcosolium, which has partly survived to us on the north wall of the bema (Brooks 2013: 323).

The church-burial complex has survived into the mid-fifteenth century until its conversion to a mosque, by the grand vizier Mesih Ali Pasha under the reign of Beyazıt II (Müller-Wiener, 1977: 103).

In his sixteenth-century visit to Constantinople, the French traveler Pierre Gilles writes the following lines about the church: ‘Myreleos inside of which was a cistern, the roof of which supported with sixty marble columns’ (Petrus Gyllius. Iii. VIII). The sixteenth-century traveler’s description of the structure refers to the cistern-palace complex that was first studied by K.Wulzinger (Striker 1981: 3). A team led by T. Macridy and D.T. Rice excavated the structure in 1931, and R. Naumann in the years 1965 and 1966.

Although the evidence about the architectural design of the tenth-century church, and how it relates architecturally to the Romanus' palace complex is scarce, Striker suggests that the first church was also a two-storied structure, constructed only by ashlar and brick, in dialogue with the late antique rotunda (of which diameter reaches 41.80 m) (Striker 1981: 11). Today Bodrum Camii still stands on the rectangular platform of which dimensions reaches up to 13.10 x 24.10 meters. Largely based on its masonry, Striker argued that the Palaeologan remodeling predominately consisted of the rebuilding of the central apse, the attic zone of the cross-arms, and possibly the closure of the large openings on the north and south facades, and creating today's cross in square plan (Striker, 1981: 10-11).

VR Tour

Map Location

Bibliography

- Brooks, S. “Women’s Authority in Death: The Patronage of Aristocratic Laywomen in Late Byzantium,” Female Founders in Byzantium and Beyond, ed. Galina Fingarova (2013): 317-32.

- Conat, Kenneth John, A Brief Commentary on the Early Medieval Church Architecture (Baltimore, 1942).

- Ebersolt, Jean. Les Églises de Constantinople (London, 1979): 137-47.

- Freshfield, E., 'Notes on the Church Now Called the Mosque of the Kalenders at Constantinople,' Archaeologia 55 (1897): 431-38.

- Hayes, J.W. “The Excavated Pottery from the Bodrum Camii,” in The Myrelaion (Bodrum Camii) in Istanbul. ed. Striker, C. (Princeton, 1981): 36-41.

- Gurlitt, C., Die Bauten Konstantinopels (Berlin, 1912).

- Mango, Cyril, Byzantine Architecture (New York, 1985).

- Mathews, Thomas. F. The Early Churches of Constantinople (Pennsylvania, 1971).

- Millingen, van. Alexander. Byzantine Churches in Constantinople (London, 1912): 196-200.

- Naumann, Rudolf, “Der antike Rundbau beim Myrelaion und der Palast Romanos I Lekapenos,” IstMitt 16 (1966): 199-216.

- Naumann, Rudolf, “Bodrum Camii (Myrelaion) Kazısı," İstanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Yıllığı 13-14 (1966).

- Niewöhner, Philipp, “The Rotunda at the Myrelaion in Constantinople: Pilaster Capitals, Mosaics, and Brick Stamps,” Papers Presented at the Second International Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Studies Conference: The Byzantine Court: Source of Power and Culture, (Istanbul, 2010): 41-53.

- Niewöhner, Philipp, “Der Frühbyzantinische Rundbau beim Myrelaion in Konstantinopel. Kapitelle, Mosaiken und Ziegelstempel,” IstMitt 60 (2010): 411-59.

- Ötüken, Yıldız, “İstanbul Kiliselerinin Fetihten Sonra Yeni Görevleri, Banileri ve Adları,” HSBBD, X/2 (1979): 71-85.

- Πασπάτης, Αλέξανδρος, Βυζαντιναί μελέται Τοπογραφικαί και ιστορικαί (Κωνσταντινούπολης, 1877): 334-36.

- Striker, L. Cecil, “Bodrum Camii'nde Yeni Bir Araştırma ve Myrelaion Problemi,” AAMusIst 13/14 (1966): 71-75, 210-15.

- Striker, L. Cecil, The Myrelaion (Bodrum Camii) in Istanbul (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1981).

- Striker, L. Cecil, “A New Investigation of the Bodrum Camii and the Problem of the Myrelaion,” Annual of the Archaeological Museums of Istanbul 13-14, 1966: 210-215.

- Talbot Rice, David, “Excavations at Bodrum Camii, 1930,” Byzantion 8 (1933): 151-74.

- Talbot Rice, David, “British Excavations at Constantinople,” Antiquity 4 (1930): 419-420.

- Van Millingen, Alexander. Byzantine Churches in Constantinople (London: Variorum Reprints, 1974): 196-201.

- Walter, Christopher, Art and Ritual of the Byzantine Church (London, 1982).

- Wulzinger, Kurt, Byzantinische Baudenkmäler zu Konstantinopel auf der Seraispitze, die Nea, das Tekfur-Serai und das Zisternenproblem (Hannover, 1925).