Çemberlitaş Sütunu, Porphyry Column

Emperor Constantine I (306-37)

ca. 328 CE

Description

History

Among Emperor Constantine’s most prominent projects in Constantinople was the construction of his Forum, a circular, colonnaded square that served the civic and ecclesiastical authorities of the new imperial capital.1 At the center of that monumental urban space stood a Porphyry Column that bore a colossal bronze statue of Constantine as Helios (Sun God) holding a spear in his right hand and a globe in the left and wearing a crown with seven rays.2 The Column that still survives today on Yeniçeriler Caddesi is called Çemberlitaş (the banded or girted stone), a word referring to the iron rings that were fitted to the entire shaft for stabilization purposes in the early fifth century.3 The statue of Constantine was set up in 328 but collapsed, as Anna Komnene relates, in 1105/6 during a violent storm.4 It was subsequently replaced with a cross by Manuel I Komnenos (1143-80). The only still-surviving inscription was set on the third band in the lower section of the cylindrical capital and recorded the Column’s renovation by Manuel Komnenos: Τὸ θεῖον ἔργον ἐνθάδε φθαρὲν χρόνῳ καινεῖ Μανουὴλ εὐσεβὴς αὐτοκράτωρ (The entire work which time had damaged was renewed by the pious emperor Manuel).5 Manuel’s work included the replacement of the original Corinthian capital that supported Constantine’s statue with the present cylindrical capital of Prokonnesian marble.6

The present-day stone base, which covers the lower part of the Column’s shaft, was added during repair works following a damage caused by fire in 1779.7

Though contemporary descriptions of the Column abound and tend to proliferate in the Middle and Late Byzantine periods, contemporary authors provide scanty, and often contradicting, information about the origins of Constantine’s statue or of the Column itself, while mentioning in passing the gradual accumulation of Christian relics underneath the Column’s base.8 In fact, Constantine of Rhodes (10th century) recounts that the 12 baskets of bread from Christ’s Multiplication of the Loaves were buried beneath the Column, as noted by George Harmatolos already in second half of the ninth century and by George Kedrenos in the eleventh.9 The only non-Christian relic is said to have been the Palladion from Rome, a wooden statue (xoanon) allegedly placed by Constantine in the foundations of the Column.10 Recent scholarship has noted that not long after its erection Constantine’s Column began to acquire a mythical meaning in collective memory and came to be regarded by the city’s inhabitants and foreign visitors as a wonder.11

It has been suggested that the bronze statue of Constantine, which was likely a re-used earlier statue adapted for him, would have resembled the lost Colossus of Sol Invictus in Rome, Constantine’s own acrolithic statue now surviving in fragmentary condition at the Capitoline Museum, and the legendary Colossus which stood at the entrance of the harbor of Rhodes.12 Writing in the tenth century, Leo Grammaticus reports that he read the following inscription on the statue’s radiant crown: “To Constantine who shines as equal to the sun.”13 However, the only still-surviving inscription is that of Manuel Komnenos. In fact, after a recent on-site study of the Column’s upper part, Robert Ousterhout has demonstrated that the heavy block that currently rests on top of the inscribed capital may belong to the Constantinian era.14

The grandeur of Constantine’s statue coupled with the lavish construction material and monumental scale of the Column augmented the visibility of the monument within the urban landscape of the newly-founded city. At the same time, however, the steady Christianization of the Byzantine Empire propelled a need for a fresh re-conceptualization of Constantine’s fundamentally pagan image atop his Column. The position of the Column in the Forum of Constantine along the main city road, the Mese, was far from accidental as, from the start, such imperial monuments constituted key locations in civic rituals and imperial processions.15 In the tenth century, the Book of Ceremonies reports that 46 of 68 ecclesiastical ceremonies stopped there, while on four of these occasions the patriarch entered a small chapel of St Constantine that was built at the foot of the Column possibly in the period of Iconoclasm.16 The Porphyry Column became a symbol of eternal victory and protection for the city and its inhabitants already by the fifth century, while Constantine came to be recognized and celebrated as saint.17 Due to its prominent height and meaning, the monument had a significant and long-lasting effect on the late antique and medieval cityscape that eventually reflected on the writings of several post-Constantinian authors.

History of Archaeological Work

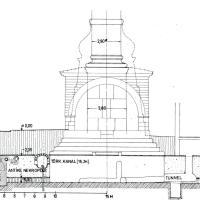

Limited archaeological work at the foot of the Column was carried out in 1929-30 by the Danish theosophist Carl Vett, whose efforts to discover the various relics allegedly buried there ended in failure. Vett’s endeavor, however, revealed the original fourth-century level at approximately 2.2 m below the present-day road but also established the width of the platform and that of the pedestal at 8.35 m and 3.80 m respectively.18 With a tall base and a shaft consisting of seven drums of porphyry, Constantine’s Column rose approximately 35.8 m. above the present-day pavement. Robert Ousterhout was able to examine the current form of the Column in 2002, when scaffolding was erected for preservation purposes.19

- 1. On the Forum of Constantine, see Müller-Wiener 1977: 255-57, with prior bibliography. Bauer 1996: 173-77; Bassett 2004: 192-204.

- 2. The Column’s architecture has been the subject of a rigorous scholarly discussion. See Mango 1965: 305-13; Mango 1981: 103-10; Mango 1993: 1-6; Bardill 2012: 28-63. See now Ousterhout 2014: 304-26; Yoncacı Arslan 2016: 121-45, both with previous bibliography.

- 3. Chronicon Paschale 573; translation in Whitby and Whitby 1989: 65. See also, Mango 1965: 307.

- 4. Alexiad 370: 55-7; translation in Dawes 1967: 309.

- 5. For the most recent reading of the inscription and detailed description, see Ousterhout 2014: 314-15, fig. 9-11.

- 6. Janin 1964: 83; Ousterhout 2014: 314-17.

- 7. Ousterhout 2014: 306; Yoncacı Arslan 2016: 125.

- 8. Bassett 2004: 192-204, includes most references. For a comprehensive review of the textual record, see also Ousterhout 2014: 308-10. On the statue’s Phrygian provenance, see John Malalas, Chronographia 246: 7; translation in Jeffreys, Jeffreys, and Scott 1986: 174. Cf. Chronicon Paschale 528: 328; translation in Whitby and Whitby 1989: 16. Cf. John Zonaras, Epitome historion III, 18: 9.

- 9. Constantine of Rhodes, On Constantinople and the Church of the Holy Apostles 24: 77-80; George Monachos Chronicon II, 500; George Kedrenos Synopsis historion I, 565.

- 10. John Malalas, Chronographia 246: 7; translation in Jeffreys, Jeffreys, and Scott 1986: 174. On the alleged relic content, see Wortley 2004: 487-96; Klein 2004: 31-59; Klein 2006: 79-100, at 81.

- 11. See Bassett 2004: 69-71; Yoncacı Arslan 2016: 127. See Ousterhout 2014: 310, who argues that the Column alongside the collection of relics engaged with Constantinople’s new position as an imperial Roman city. See James 2012: 171-2, for commentary on the poem by Constantine of Rhodes and his depiction of the Column.

- 12. For a discussion of the statue’s original form, see Ousterhout 2014: 312-14. See also, Bardill 2012: 84-104. See Yoncacı Arslan 2016: 128-31, who looked for the Column’s precedents.

- 13. Leo Grammaticus 87: 17.

- 14. Ousterhout 2014: 317.

- 15. Mango 2000: 173-88, esp. 176; Bauer 2001: 27-61; James 2012: 160-70.

- 16. De Ceremoniis 74, 164, 439, 502; translation in Moffatt and Tall 2012: 74, 164, 439, 502. It is noteworthy that sometime before the tenth century a new church dedicated to the Theotokos was built in the Forum of Constantine. On the chapel of St Constantine, see Mamboury 1955: 275-80; Mango 1981: 103-10.

- 17. Constantine of Rhodes, On Constantinople and the Church of the Holy Apostles 22-24: 71-82. See also, James 2012: 164. Ousterhout 2014: 320-26, attempts to explain the talismanic effect of the statue of Constantine and its visual connotations through time. On Constantine’s sainthood, see Dagron 2003: 143-48; Wortley 2006: 355-61.

- 18. See Mango 1981: 103-4, who records that the location and condition of Vett’s dossier remains unknown. See additionally, Dalleggio d'Alessio 1930: 339-41; Fıratlı 1964: 207-9.

- 19. Ousterhout 2014: 304-26, stems from that brief but rare study campaign.

Map Location

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Alexiad in Reinsch, D. and Kambylis A. (eds.) 2001. Annae Comnenae Alexias, Berlin-New York. Translation in Dawes, E. 1967. The Alexiad of the Princess Anna Comnena, London.

Chronicon Paschale in Dindorf, L. (ed.) 1832. Chronicon Paschale, Bonn. Translation in Whitby, M. and Whitby, M. 1989. Chronicon Paschale 284-628 AD, Liverpool.

Constantine of Rhodes, On Constantinople and the Church of the Holy Apostles in James, L. (ed.) 2012. Constantine of Rhodes, On Constantinople and the Church of the Holy Apostles: with a new edition of the Greek text by Ioannis Vassis, Ashgate.

De Ceremoniis in Reiske, J. (ed.) 1829. Constantini Porphyrogeniti imperatoris de cerimoniis aulae Byzantinae libri duo, Bonn. Translation in Moffatt, A. and Tall, M. 2012. Constantine Porphyrogennetos: The book of ceremonies with the Greek edition of the Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae (Bonn, 1829), Canberra.

George Kedrenos, Synopsis historion in Bekker, I. (ed.) 1838. Georgius Cedrenus, Ioannis Scylitzae Operae, Bonn.

George Monachos, Chronicon in de Boor, C. and Wirth, P. (eds.) 1978. Georgii Monachi Chronicon, Stuttgart.

John Malalas, Chronographia in Thurn, J. (ed.) 2000. Ioannis Malalae Chronographia, Berlin, New York. Translation in Jeffreys, E., Jeffreys, M., and Scott, R. 1986. The Chronicle of John Malalas: A Translation, Sydney.

John Zonaras, Epitome historion in Büttner-Wobst, T. (ed.) 1897. loannis Zonarae Epitomae Historiarum libri xviii, Bonn.

Leo Grammaticus in Bekker, I. (ed.) 1842. Leonis grammatici chronographia, Bonn.

Secondary Sources

Bardill, J. 2012. Constantine: Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge.

Bassett, S. 2004. The Urban Image of Late Antique Constantinople, Cambridge.

Bauer, A. 1996. Stadt, Platz und Denkmal in der Spätantike. Untersuchungen zur Ausstattung des öffentlichen Raums in den spätantiken Städten Rom, Konstantinopel und Ephesos, Mainz.

Bauer, A. 2001. “Urban Space and Ritual: Constantinople in Late Antiquity,” in Rasmus Brandt, J. and Steen, O. (eds.), Imperial Art as Christian Art - Christian Art as Imperial Art: Expression and Meaning in Art and Architecture from Constantine to Justinian, Rome, 27-61.

Dagron, G. 2003. Emperor and Priest, the Imperial Office in Byzantium, Cambridge.

Dalleggio d’Alessio, E. 1930. “Les fouilles archéologiques an pied de la colonne de Constantin à Constantinople,” Échos d’ Orient 159, 339-41.

Fıratlı, N. 1964. “Short Report on Finds and Archaeological Activities,” Istanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri Yıllıği 11-12, 207-9.

Janin, R. 1964. Constantinople byzantine: dévelopment urbain et répertoire topographique, Paris.

Klein, H.A. 2004. “Constantin, Helena, and the Cult of the True Cross in Constantinople,” in Durand, J. and Flusin, B. (eds.), Byzance et les reliques du Christ, Paris, 31-59.

Klein, H.A. 2006. “Sacred Relics and Imperial Ceremonies at the Great Palace of Constantinople,” in Bauer, A. (ed.), Visualisierungen von Herrschaft - frühmittelalterliche Residenzen Gestalt und Zeremoniell, Istanbul, 79-100.

Mamboury, E. 1955. “Le Forum de Constantin; la chapelle de St. Constantin et les mystères de la Colonne Brulée. Resultats des sondages opérés en 1929 et 1930,” in Πεπραγμένα του Θ’ Διεθνούς Βυζαντινολογικού Συνεδρίου: 12-19 Απριλίου 1953. Θεσσαλονίκη 1953, Athens, 275-80.

Mango, C. 1965. “Constantinopolitana,” Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 80, 305-36.

Mango, C. 1981. “Constantine’s Porphyry Column and the Chapel of St Constantine,” Δελτίον της Χριστιανικής Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας 10, 103-10.

Mango, C. 1993. “Constantine’s Column,” in eadem, Studies on Constantinople, Ashgate: Aldershot, 1-6.

Mango, C. 2000, “The Triumphal Way of Constantinople and the Golden Gate,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 54, 173-88.

Müller-Wiener, W. 1977. Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17. Jh., Tübingen.

Ousterhout, R. 2014. “The life and afterlife of Constantine's Column,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 27, 304-26.

Wortley, J. 2004. “The Legend of Constantine the relic-provider,’’ in Egan, R.B. and Joyal, M. (eds.). Daimonopylai: Essays presented to E.G. Berry, Winnipeg, 487-96.

Wortley, J. 2006. “The ‘Sacred Remains’ of Constantine and Helena,” in Burke, J. et al (eds.), Byzantine narrative: papers in honour of Roger Scott, Melbourne, 351-67.

Yoncacı Arslan, P. 2016. “Towards a New Honorrific Column: the Column of Constantine in Early Byzantine Urban Landscape,” METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture 33 (1), 121-45.