St John Stoudios Monastery, Mone tou Prodromou en tois Stoudiou, Stoudion

Patrician Studius

ca. 450 CE

Description

Imrahor Camii, the former katholikon of the Stoudios Monastery, the oldest ecclesiastical building of Byzantine Contantinople is situated in today's Samatya neighborhood, in close distance to the remains of the Golden Gate, the monumental entrance to the Byzatine Constantinople. Samatya, the Psamathia region of the Byzantine Constantinople is renowned for the Greek orthodox monastic establishments, which would be later largely replaced by the Armenian Orthodox ecclesiastical buildings.

The history of the monastery of St. John the Forerunner Stoudios, which supposedly kept the reliquary for the skulls of Saint John, can be traced back to the fifth century (Typikon of the Stoudios, 68). The years 463 and 454 are proposed as the exact foundation date for the monastery based on two historical accounts, respectively the Chronicles of Theophanes and the Palatine Anthology, which was the date regarded as more reliable according to Cyril Mango (Mango 1978: 115; Müller-Wiener 1997: 147). The Palatine Anthology tells us that a certain Stoudios, who served as the eastern consul in the year 454 is believed to be the first founder of the monastic complex (Janin 1951, 444; Typikon of the Stoudios Monastery, tr. Miller 2000, 67). However, the later analysis of Urs Perschlow (1984) and Jonathan Bardill (2004) has pushed back the construction date of the monastery to 450, largely based on the production date of the stamped bricks used in the construction of the monastery church (Bardill 2004: 32, 60-61, 109).

Irrespective of its exact construction date, around the year 460, the founder Stoudios invited a group of monks allegedly called as akoimetoi, the ‘sleepless monks’ (Typikon of the Stoudios, 68). The akoimetoi supposedly remained in the monastic complex at least until the end of the eighteenth century, when they were expelled from the capital by the iconoclastic emperor Constantine V (Typikon of the Stoudios, 68).

In the year 787, the monastery has started to gain a leading role in Constantinople, as Sabbas, the higoumenos of the monastery was invited to the second council of Nicaea 9 (Janin 1951, 445). Following the restoration of icons, the Empress Irene summons the erudite Theodore from the Bithynian monastery at Sakkoudion, which he was in charge together with his uncle Plato (Typikon of the Stoudios, 68). In the time of Theodore, the monastic complex grew rapidly as it is attested that the number of monks reached 700 (Janin 1951, 445). In this flourishing period of the monastery, the complex incorporated a school that focused on the teaching of calligraphy, painting, hymnography, miniature, and became one of the most important intellectual centers of Constantinople (Janin 1951, 445).

Under Leo V, in the second wave of the iconoclasm, Theodore was exiled once more, and had to remain in a monastery near Smyrna, until he was called back to the capital by the Emperor Michael II in 821. Yet Theodore died in exile in the Prinkipo islands in 826, and his remains were transferred, and buried in the Stoudios monastery in 844 (Typikon of the Stoudios, 69).

In the Komnenian period, the monastery seems to remain silent, and was respectively stripped off its relics in the Fourth Crusade. Following the reconquest of the capital, the brother of Emperor Andronikos II, Constantine Palaiologos restored the monastery (Typikon of the Stoudios, 69). Under the reign of John VIII, a synod about the election of the metropolites was held in the church. Possibly being the last information on the Byzantine period of the structure, in 1432, John Bryennios retreat in a cell in the monastery. The name of the last higoumenos who was in charge of the monastery in December of 1452 is attested in the sources, few months before the conquest of the city by the Ottomans.

The monastery church was not converted until the reign of Sultan Beyazid I (1481-1512), who granted the monastic property to an Ottoman high officer, Ilyas Bey bin Abdullah, the stable-master or the shield-bearer (imrahor in Ottoman). (Typikon of the Stoudios, 69).

In 1403, the Spanish traveler de Clavijo writes about the church in detail, which is chronologically followed by Christoforo Buondelmonti’s representation of the church that was in ruined condition (Müller-Wiener 1997: 147). Over the following centuries, the monastery is mentioned in other travelers’ accounts, such as the sixteenth century account of Pierre Gilles. In the last decades, the monastery was completely rebuilt following the conflagration in 1782, supposedly in 1804-5, and later in 1908, following the earthquake that stroke the city in 1894 and devastated the entire neighborhood (TAY V.8 Stoudios Manastırı).

History of Archaeological Work

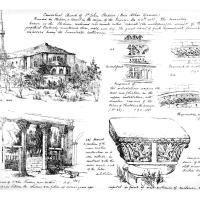

In the years 1907-9, a team from the Russian Archaeological Institute in Constantinople led by B.A. Panchenko undertook the first systematic archaeological survey of the site, through which they have been able to uncover the remains of a fifth-century cruciform crypt, and three tombs in the southern aisle (Guiglia et all: 2009: 312; Typikon of the Stoudios 70). In addition to the architectural discoveries, the Russian team presented the first documentation of the early Byzantine period’s marble decoration from the opus sectile floor to the architrave and column capitals.Following a devastating fire in 1920, Jean Ebersolt and Van Millingen published the first accurate architectural plan of the basilical structure. Based on the remains of a cistern situated on the southern part of the monastic complex, the two scholars argued that the monastic property extended towards the Propontis shore, and included the remains of another chapel dedicated to Theotokos (Typikon of the Stoudios 70).Over the last years, another research group directed by Alessandra Guiglia from Sapienza University in Rome, in collaboration with Claudia Barsanti has made the latest contribution to the documentation of the structure by a reconsideration of the rich marble architectural elements that decorated the basilica (Guiglia et all 2008). Ranging from Pavonazzetto to the Thessalian marble, the basilica was decorated with all kind of marbles, which also testifies the importance of the structure being parallel to the scale of the architectural patronage.Being one of the largest and prominent monastic complexes of Byzantine Constantinople, which played a leading role in the religious and political disputes of the Byzantine capital for centuries, the Monastery of Saint John Stoudios, now listed as the Pious Foundations property, has been left in ruin for decades for a potential conservation or restoration project.

Map Location

Bibliography

- Beck, Hans-Georg, Kirche und Theologische Literatur im Byzantinischen Reich (Munich, 1959): 491-95.

- Barsanti, Claudia, “The Marble Floor of St. John Studius in Constantinople: A Neglected Masterpiece,” in 11th International Colloquim on Ancient Mosaics October 16th-20th, 2009, Bursa, Turkey, Mosaics of Turkey and Parallel Developments in the Rest of the Ancient and Medieval World: Questions of Iconography, Style and Technique from the Beginnings of Mosaic until the Late Byzantine Era, Ed. Mustafa Sahin (Istanbul, 2010): 87-99.

- Barsanti, Claudia, ''Il San Giovanni'', in C. Barsanti, A. Paribeni, 'Broken Bits of Byzantium: frammenti di un puzzle archeologico nella Constantinopoli di fine Ottocento', Immagine e ideologia. Studi in onore di Arturo Carlo Quintavalle (Milano,2007): 550-565.

- Delehaye, Hippolythe, Stoudion-Stoudios, Analecta Bollandiana LII (1934): 64.

- Ebersolt, Jean. Les Églises de Constantinople (London, 1979): 1-19.

- Ettinghausen, Elisabeth S., “Saint John Studios (İmrahor Camii)”, A Lost Art Rediscovered. The Architectural Ceramics of Byzantium, ed. by S. E. J. Gerstel, J. A. Lauffenburger, (Baltimore, 2001): 203-207.

- Forschheimer, P.- J. Strzygowski, Die Byzantinischen Wasserbehalter von Konstantinopel (Wien, 1893).

- Hermann, Basilius, “Eucharistische Sitten im Leben des Hl. Theodor Studites,” Liturgie und Kunst 4 (1923): 76–80.

- Guiglia, Alessandra; Barsanti, Claudia; Pedone, S., “St. Sophia Museum Project 2007. The marble sculptures of St. John Studius (Imrahor Camii),” Araştırma Sonuçları Toplantısı 26-3 (2009): 311-328.

- Günözü, Hande, “Restorasyon-Konservasyon: Imrahor Ilyas Bey Cami (Stoudios Manastır Kilisesi) Dış Cephe Sıva-Harç Analiz Sonuçları,” Art-Sanat 2 (2014): 275-289.

- Janin, Raymond, La Géographie Ecclésiastique de L'empire Byzantin, Première Partie: Le siège de Constantinople et le patriarcat oecuménique, Les Églises et les monastères (Paris, 1969): 444-455.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, Talbot, Alice-Mary, and Cutler, Anthony, “Stoudios Monastery,” ODB: 1960–61.

- Küçükdogan, Bilge, “Seismic assessment of Monastery of Stoudios (Imrahor Mosque) in Istanbul,” Advanced Materials Research (2010): 721 - 726.

- Leroy, Julien, “L’influence de saint Basile sur la réforme studite d’après les Catéchèses,” Irénikon 52 (1979): 491–506.

- Mango, Cyril, “The Date of the Studius Basilica at Istanbul,” B&MGS 4 (1978): 115–22.

- Mathews, Thomas, The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey (University Park, Pa., 1976): 143–58.

- Mendel, Gustave, Musées Imperiaux Ottomans. Catalogue des sculptures grecques, romaines et byzantine II (Constantinople, 1914): 453.

- Miller, Timothy, “Theodore Studites: Testament of Theodore the Studite for the Monastery of St. John Stoudios in Constantinople,' in Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents, A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments. Ed. by John Thomas and Angela Constantinides Hero with the assistance of Giles Constable, Dumbarton Oaks (Washington, 2000): 67-83

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang, Bildlexikon Zur Topographie Istanbuls. (Tübingen, 1977): 147-152.

- Peschlow, Urs, “Die Johanneskirsche des Studios in Istanbul,” XVI. Internationaler Byzantinistenkongreß AKTEN II/4, Jahrbuch der Üsterreichischen Byzantinistik, 32- 4 (1984): 429-435.

- Thieme, T. “Metrology and Planning in the Basilica of Johannes Stoudios,” Le dessin d'architecture dans les sociétés antiques. Actes du Colloque de Strasbourg 26-28 janvier 1984: 291-308.

- Werner, E., “Die Krise im Verhältnis von Staat und Kirche in Byzanz: Theodor von Studion,” Berliner byzantinische Arbeiten 5 (1957): 113–33.

- Van Millingen, A., Byzantine Churches in Constantinople, Their History and Architecture (London, 1912): 35–61.

- For a recent initiative concerned with the preservation state of the structure: See the link below: http://www.stoudiosmonastery.com