Kyriotissa Monastery

Unknown

1197-1204

Description

Kalenderhane Camii, the former katholikon of the Virgin Kyriotissa monastery, is located on the third hill of Byzantine Constantinople, in close distance to the Valens Aqueduct, in today’s Vezneciler neighborhood, overlooking the Propontis (Marmara) shore.

Kalenderhane Camii still remains as one of the best-studied and likewise best-published Byzantine monuments in Istanbul, largely owing to the large-scaled archaeological project conducted by Cecil Striker and Dogan Kuban in the period between 1966 and 1977, prior of its restoration by the Pious Foundations.

Although the Middle Byzantine history of the monastic complex has been largely understood, the intricate multi-phased character of the site – Cecil Striker has identified eight major archaeological layers- still poses various peculiarities (Striker 1997).

Based on the archaeological evidence, the earliest phase of the monastic complex dates back to the late Roman period, predominantly characterized by the remains of a medium-sized late antique bath complex (Müller-Wiener 1977: 153). Located on the northwestern end of the katholikon of the monastery, the circular bath provided water from the Valens aqueduct, and was later abandoned for an unclear reason, for the construction of a basilical single-apsed structure that leaned the aqueduct from its northern facade (Striker and Kuban 1975: 306-8). This previously unknown late sixth-century chapel that was uncovered for the first time by Striker was oriented slightly towards the southeastern direction. The only well-preserved feature of the structure, namely its apse is surrounded from the inner side with an one-stepped synthronon, and communicated with the katholikon’s prosthesis through an opening inserted to its southern wall in the following centuries.

A mosaic panel depicting the Presentation to the Temple, now kept in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, framed by a geometric opus-sectile band was excavated in the sixth-century church’s apse without any relation to the architectural body (Striker and Kuban 1975: 308).

The later architectural phases of the building complex relates to the construction of the katholikon. The architectural characteristics of the main church’s apse together with the archaeological context suggest that the construction of the church started sometime in the late seventh century, and continued through the tenth century when the two chapels were added to the south of the main apse, and the north area of the katholikon, had been started to be used for burials (Striker 1997: 8).

Prior to the Fourth Crusade, the monastery was largely destroyed by the conflagration in 1197, when the monument was possibly recorded in a poem of Constantine Stilbes as the monastery ta Kyrou, a name generating from the same root with Kyriotissa according to Paul Magdalino (Stiker 1997:8).

Following the destruction caused by the fire, the katholikon was reconstructed hastily, and continued to be remodeled under the Latin occupation of the city, as one of the chapels was decorated by the fresco cycle of St. Francis (Striker 1997). Although the historical witnesses of the Palaeologean period remains scarce, the architectural survey of the structure revealed various changes such as the Palaeologean wall that cut the diaconicon from the east blocking the Latin chapels.

In 1453, the monument was one of the few Byzantine churches that had been converted into a mosque. The Ottoman sultan Mehmed II bestowed the church to the Kalenderi dervishes who played an important role in the city’s conquest. The vakfiye (foundation) documents imply that the property of the new congregational mosque extended from the Thrace to the baths situated in Galata (Müller-Wiener 1977: 156).

In the sixteenth century, the monument had been visited, and documented by the French traveler, Pierre Gilles who without proposing any identification, ‘refers to its beautiful marble revetment – vestita crustis varii marmoris-’ (Van Millingen 1912:183).

In the eighteenth century, another prominent architectural benefactor of the Ottoman empire, Haci Besir Aga, who served as the chief black eunuch under the reigns of the Ahmed III and Mahmud I, has restored the building around the year 1747 by adding a new mihrab (qibla niche), minber (imam’s pulpit) and mahfil (sultan’s lodge) (Müller-Wiener 1977: 156).

Over the nineteenth century, the access to the monument has remained largely restricted to the Muslim community, as A.G. Paspates has been only able to document the monument from the exterior (Van Millingen 1912:184).

Architectural Features: Church's Plan and Decoration

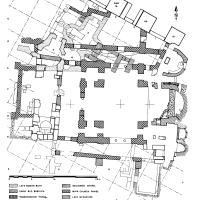

The monastery's katholikon was originally designed as a cross-dome type, with its central body (19x19 m. in longitude and 8 m. in diameter) surrounded by a number of additional side aisles, a narthex, an exonarthex, and two chapels, known as the ‘Melismos and Francis’ chapels in the literature.

As evidenced by the archaeological context, the two Latin-period chapels constructed in the diakonikon, were decorated by the frescoes commisioned by the Franciscan friars. The so-called St. Francis Fresco Cycle represents St. Francis, standing in frontal posture ‘supports an open book with his left hand, and with his right hand in the gesture of speaking’ (Striker and Kuban 1975: 313). The saint is flanked by ten scenes from his life, divided equally in each sides, which is commented to be ‘a Crusader adaptation of the standard Dugento Italo-Byzantine icon retable’ (Striker and Kuban 1975: 313).

Beside the church's marble revetments first mentioned by Pierre Gilles, the monastic complex yielded many marble elements such as fragments of architectural sculptures, inlaid icons (one identified as the annunciation icon) and one sarcophagus lid decorated by griffons, sphinxes, peacocks and a cross on the opposite side (Striker and Kuban 1975: Fig.12).

VR Tour

History of Archaeological Work

Prior to the restoration of Kalenderhane Camii by the Vakiflar General Directorate, Cecil L. Striker from the University of Pennsylvania was granted the permission to conduct an archaeological field project at Kalenderhane in collaboration with Dogan Kuban (Striker 1997: 1). The first archaeological campaign has started in 1966, and lasted approximately fifteen years, with the last season in 1980 when the restoration work of the frescoes had been completed with the collaboration of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums.

Map Location

Bibliography

- Ayvansarayi, Hüseyin bin Ismail, Hadikat-ül Cevami (Istanbul, 1894): I. 166, 16.

- Brill, Robert B., “Chemical Analyses of the Zeyrek Camii and Kariye Camii Glasses,” DOP 59 (2005): 213-30.

- Ebersolt, Jean. Les Églises de Constantinople (London, 1979): 91-111.

- Freshfield, Edwin, “Notes on the Church Now Called the Mosque of the Kalenders at Constantinople,” Archaeologia 55 (1897): 431-38.

- Janin, Raymond, La Géographie ecclésiastique de l'empire Byzantin, première partie: le siège de Constantinople et le patriarcat oecuménique, les églises et les monastères (Paris, 1969).

- Marinis, Vasilis, Architecture and Ritual in The Churches of Constantinople: Ninth to Fifteenth Centuries (New York, 2014): 163-67.

- Millingen, Alexander van, Byzantine Churches in Constantinople: Their History and Architecture (London, 1912): 183-190.

- Mordtmann, Andreas David, Esquisse topographique de Constantinople (Paris, 1892)

- Mühlmann, F., “Kalender-Khane-Dschamissi zu K'opel- Eine Byzantinische Kirche,” ZeitschrBildKunst 21 (1886): 49-51.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang, Bildlexikon zur Topograhie Istanbuls (Tübingen, 1977): 153-8.

- Striker, Cecil L. and Doğan Kuban, “Work at Kalenderhane Camii in Istanbul, First Preliminary Report,” DOP 21 (1967): 267-71.

- Striker, Cecil L. and Doğan Kuban, “Work at Kalenderhane Camii in Istanbul, Second Preliminary Report,” DOP 22 (1968): 185-93.

- Striker, Cecil L. and Doğan Kuban, “Work at Kalenderhane Camii in Istanbul, Third and Fourth Preliminary Report,” DOP 25 (1971): 251-58.

- Striker, Cecil L. and Doğan Kuban, ed. Kalenderhane in Istanbul: The Buildings, Their History, Architecture and Decoration : Final Reports on the Archaeological Exploration and Restoration at Kalenderhane Camii 1966-1978 (Mainz, 1997).

- Striker, Cecil L. and Doğan Kuban, ed. Kalenderhane in Istanbul: The Excavations: Final Reports on the Archaeological Exploration and Restoration at Kalenderhane Camii 1966-1978 (Mainz am Rhein, 2007).

- Talbot, Alice Mary, “The Restoration of Constantinople under Michael VIII,” DOP 47 (1993): 243-61.