Ta Gastria Monastery

Theoktiste, mother of Empress Theodora (died after 842)

14th century

Description

Architecture

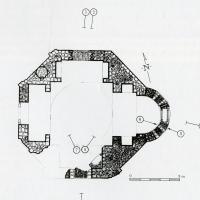

In 1877, Alexandros Paspates was the first to identify Sancaktar Hayrettin Mescidi as belonging to the Byzantine monastery of ta Gastria. In his description of the site in the nineteenth century, Paspates took notice of the extensive overgrown garden adjacent to the modest building, and hinted at the existence of a larger monastic complex.1 The building was converted into a mosque in the fifteenth century by Sancaktar Hayrettin Efendi, who might have been buried there.2 The Sancaktar Hayrettin follows the octagon design on the exterior and the fully articulated Greek cross plan on the interior. Writing in 1912, Alexander Van Millingen noted that the apse belonged to a different construction phase from the core structure for which he suggested a fourteenth-century date.3 Investigating the site shortly afterwards, Aristeides Pasadaios published a relatively accurate plan of the structure and, in emphasizing the lack of exact correspondence between apse and main part, proposed a fourth to sixth century date.4 These views were taken up by Thomas Mathews, who considered the possibility that the building at some point changed function, from secular to ecclesiastical.5 Most recently, Wolfang Müller-Wiener followed previous scholarship and provided a brief note on the architectural characteristics of the building, adding a re-constructed plan that shows it as a domed octagonal church. Marshalling all scholarship published earlier, Müller-Wiener was able to visit the ruinous building just before its major restoration (1973-75) and introduce a photograph of the apse as taken from the dilapidated interior. Following the subsequent renovation and alterations, it remains of significant documentary value.

History

The convent was most likely founded by Theoktiste, the mother of Empress Theodora (842-56), in the second quarter of the ninth century.6 Theoktiste is described as having acquired the property from a patrikios (high-ranking general or officer) called Niketas, in order to reside there.7 Apart from her mother, Theodora herself also received the monastic habit and retired at ta Gastria, certainly after 858 and before 867 (the year of her death).8 Not long after Theodora’s attempted attack against her brother, Bardas, her five daughters, Thekla, Anna, Anastasia, Pulcheria, and Maria were removed from the palace and sent to join her at ta Gastria.9 The Book of Ceremonies informs us that Theodora along with her daughters, Anastasia, Thekla, and Pulcheria and her brother, Petronas, were evidently buried in the naos of the church. In the same passage we also read that the tomb of Theodora’s mother, Theoktiste, was established on the left-hand side of the narthex, as one faced east.10 It was probably Emperor Basil I (867-886) the one who oversaw the establishment of Theodora’s and her children’s tombs in ta Gastria.11 It is worth mentioning the unique, yet anecdotal, interpretation of the name ta Gastria that attributes the foundation to an ideal Christian empress, Helena, mother of Constantine I.12 The myth is contained in the Patria, a collection of short notices and anecdotes compiled in the tenth century, and relates that upon her return from Jerusalem Helena disembarked at the Constantinopolitan gate of Psomatheas, and planted flowers, which originally adorned the True Cross, in pots (gastrai). In her final years, Helena is said to have retired at the monastic house, which received the dedication Gastria.13

- 1. Paspates 1877: 354-57. See also, Janin 1969: 73.

- 2. Paspates 1877: 357.

- 3. Van Millingen 1912: 268-71.

- 4. Pasadaios 1965: 1-55. For the re-drawn plan, see Mathews 1976: 232.

- 5. Mathews 1976: 231.

- 6. Theophanes Continuatus 130: 5.9-13; John Skylitzes, Synopsis historion 52: 73, mentions that Theoktiste possessed a house in the proximity of ta Gastria; translation in Wortley 2010: 54.

- 7. Theophanes Continuatus 130: 5. 9-13. An alternative scenario sees Euphrosyne, Emperor Theophilos’s stepmother and spouse of Michael II (r. 820-829), as the patron of the monastery; see Pseudo-Symeon, Chronographia 217: 5. 20-22; and Life of St Theodora in Vinson 1998: 366, which follows closely Pseudo-Symeon’s account. Treadgold 1988: 271, 310, n.427, accepts the story as told by Pseudo-Symeon and rejects Theophanes’s, but provides no evidence for the former’s validity. However, the problem with the Pseudo-Symeon’s version is that corroborating evidence, including Pseudo-Symeon himself, recorded that Empress Theodora retired in ta Gastria in her final years while her relatives maintained a personal bond with the monastery: Pseudo-Symeon, Chronographia 241: 21.187-191. The issue was first raised by Markopoulos 1983: 276, who cites Theophanes’s narrative that credits the patronage of the monastery to Theoktiste. Cf. John Zonaras, Epitome historion III, 394: 5 -15. See also Signes-Codoñer 2014: 108.

- 8. Joseph Genesios 64: 11.84-87; translation in Kaldellis 1998: 80.

- 9. Leo Grammaticus 237: 3-5; John Zonaras, Epitome historion III, 358: 6 -17, 394: 5 -15.

- 10. De Ceremoniis 647-48; translation in Moffatt and Tall 2012: 647-48.

- 11. Theophanes Continuatus 248: 22.9 -14. The possible function of the foundation as a mausoleum for Theodora’s family was noted in Janin 1969: 73. See Majeska 1984: 317, who indicates that the site visited by the Russian Anonymous traveler in the late fourteenth century should not be identified as the ta Gastria monastery.

- 12. For commentary on this story, see Berger 2013: 141, n. 5.

- 13. Patria 215: 4; translation in Berger 2013: 141-3.

VR Tour

Map Location

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- De Ceremoniis in Reiske, J. (ed.) 1829. Constantini Porphyrogeniti imperatoris de cerimoniis aulae Byzantinae libri duo, Bonn. Translation in Moffatt, A. and Tall, M. 2012. Constantine Porphyrogennetos: The book of ceremonies with the Greek edition of the Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae (Bonn, 1829), Canberra.

- John Skylitzes. Synopsis historion in Thurn, I. (ed.) 1973. Ioannis Scylitzae Synopsis historiarum, Berlin. Translation in Wortley, J 2010. A Synopsis of Byzantine history, 811-1057: John Skylitzes, Cambridge.

- John Zonaras. Epitome historion in Büttner-Wobst, T. (ed.) 1897. loannis Zonarae epitomae historiarum libri xviii, Bonn.

- Joseph Genesios. in Lesmüeller-Werner, A. and Thurn, I. (ed.) 1978. Iosephi Genesii regum libri quattuo, Berlin. Translation in Kaldellis, A. 1998. Genesios on the Reigns of the Emperors, Canberra.

- Leo Grammaticus. in Bekker, I. (ed.) 1842. Leonis grammatici chronographia, Bonn.

- Patria in Preger, T. (ed.) 1901-1907. Scriptores originum Constantinopolitanarum, Leipzig. Translation in Berger, A. 2013. Accounts of Medieval Constantinople, the Patria, Cambridge, MA.

- Pseudo-Symeon. in Wahlgren, S. (ed.) 2016. Symeonis Magistri et Logothetae Chronicon, Berlin.

- Theophanes Continuatus. in Featherstone, M. and Signes-Codoñer, J. (ed.) 2015. Chronographiae quae Theophanis Continuati nomine fertur libri I–IV. Recensuerunt, anglice verterunt, indicibus instruxerunt, Berlin.

- Vinson, M. Life of St Theodora the Empress in Talbot, A.-M. (ed.) 1998. Byzantine Defenders of Images: Eight Saints’ Lives in English Translation, Washington, DC.

Secondary Sources

- Janin, R. 1969. Géographie Ecclésiastique de L’empire Byzantin, Vol. 1, Le Siège de Constantinople et Le Patriarcat Oecuménique, Pt. 3, Les Églises et Les Monastères, Paris.

- Majeska, G. 1984. Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, Washington, DC.

- Markopoulos, A. 1983. Symmeikta 5,, 249-85.

- Mathews, T. 1976. The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: a Photographic Survey, University Park, PA.

- Müller-Wiener, W. 1977. Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls : Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17. Jh, Tübingen: Wasmuth.

- Pasadaios, A. 1965. Ἐπί δύο βυζαντινῶν μνημείων τῆς Κωνσταντινουπόλεως ἀγνώστου ὀνομασίας, Athens.

- Paspates, A.G. 1877. Βυζαντιναί μελέται: τοπογραφικαί καί ιστορικαί μετά πλείστων εικόνων, Constantinople.

- Signes-Codoñer, J. 2014. The Emperor Theophilos and the East, 829-842: Court and Frontier in Byzantium during the Last Phase of Iconoclasm, Farnham: Ashgate.

- Treadgold, W. 1988. The Byzantine revival, 780-842, Stanford, CA.

- Van Millingen, A. 1912. Byzantine Churches in Constantinople, Their History and Architecture, London.