Kilise Camii, Hagios Theodoros ta Karvounaria

Unknown

ca. 1100

Description

The Middle Byzantine Structure known as Vefa Kilise Camii or Molla Gürâni Camii is located in the Vefa neighborhood, on Tirendaz Caddesi, in close distance to the Divanyolu/Mese, the main arterial street of both the Byzantine and Ottoman Constantinople.

As opposed to the monument’s prominent location, imposing architectural and decorational features that give clear insights about the structure’s prominent status, Vefa Kilise Camii has a notoriously obscure history. The French traveller Pierre Gilles who visited Constantinople in the sixteenth century is the first who has argued that Kilise Camii had to be associated to Saint Theodore, as the neighborhood was crammed with churches dedicated to the military saint. Later scholarship proposed other possibilities for the identification of the church such as the churches of Saint Procopius τῆς Χελώνης, Saint Theodore ta Karvounaria or Saint Theodore πλησίον του χαλκού τετραπύλου, and lastly the katholikon of the Monastery of Gorgoepekoos (Salzenberg, 1855; Berger 1988, 460-1; Mango 1990, 421-9; Müller-Wiener 1997: 169). The scholarly confusion centered around the identification of Vefa Kilise Camii with a Byzantine foundation is also caused by the intriguing architectural nature of the structure. The extensive use of late antique stamped bricks was hastily considered as another evidence for an earlier structure, although the practice of spoliation from earlier monuments was widespread in the middle ages.

As it stands today, Kilise Camii is now considered to have been first commissioned sometime in the tenth century, with massive architectural alterations in the later periods, as can be observed in the katholika of the monasteries of Lips, Pammakaristos and Chora (Müller-Wiener 1997: 169). Thus Vefa Kilise Camii can be listed among the Palaeologean architectural projects that developed on an already existing Komnenian churches, which most of the time cleared away the earlier history of the structure.

Architectural Features

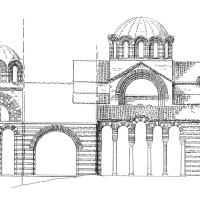

Representing the widespread ‘style of Comnene quincunx -or cross-in-square- churches constructed largely with recessed brick masonry’, the central fenestrated dome of the church rises on a dodecagonal drum carried by four columns – later replaced by rectangular pillars following the earthquake of 1883 (Krautheimer 1986: 363; Müller-Wiener 1997: 170). From the exterior, the dome’s cornice undulates, and forms a continuous dogtooth frieze on the upper register of the twelve windows.

From the east façade, one can still see the elegant brickwork that continues on the polygonal apse’s façade. Five blind windows occupy the five-sided upper register of the apse, and are followed by five –later walled-up- windows on the lower register. Today, from these five windows, only the central one flanked by two small columns with impost capitals survives.

The polygonal apse is flanked by two cruciform pastophoria, which had been altered in a significant way throughout time, as testified by their eastern facades’ masonry. The two multi-phased pastophoria rooms do not project from the eastern façade, and create two separate internal spaces that would have been isolated from the naos by a marble iconostasis. Barrel vaults and domical vaults cover the side units, which were illuminated by rows of tripartite opening, now turned to windows, both on the east and west façades.

In addition to the eastern façade, the north and south façades had been significantly altered. The marble columns that support lace worked sixth-century capitals possibly designated arched openings that once gave way to the lateral units. However at a later phase, possibly in the course of the Palaeologan reign, these northern and southern openings were walled-up, an U-shaped exonarthex enveloping the structure from the west was added (Freely-Cakmak 2004, 207). In addition to the second phase, at much later time, as we see in the Chora monastery church, the porticoed western façade of the exonarthex was blocked with early Byzantine spolia marble slabs.

Ottoman period

Following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans, the church was converted into a mosque by the grand mufti Molla Güranî Semseddîn Ahmed Efendi, who was believed to be the tutor of Mehmed II and also of Beyazid II (Müller-Wiener 1997, 169).

Under the reign of Sultan Bayezid, in 1484, Molla Ali bin Yusuf-ül-Fenari, Molla Gürani is recorded to have founded his mosque’s waqf by incorporating a number of buildings in the Vefa neighborhood, possibly with the aim of granting sufficient income for maintaining his mosque complex (Kırımtayıf 2001, 31).

According to Ayvansarayi, a mihrab, and a brick minaret with ondulating pattern were constructed for the conversion, and the minbar was added later through the personal funds of Abdurrahman Efendi, son of Eminzade Hüseyin Aga (Ayvansarayi 1987: 139-44).

Mosaic Decoration

In 1937, during the archaeological excavations and cleaning works conducted by Miltiadis Nomidis and Hidayet Fuat Tagay, Nomidis was able to uncover the figural mosaic decorations that decorated the ribs of the exonarthex’s cupola (Janin, 1969: 155; Mamboury 1938, 307). Despite the continuous damage in the last years, it is still possible to see the depictions of the old Testament prophets -eight in number, and from north identified as Azor, Sadoc, Achim, Jechonias, Salathiel, Zorobabel, Abuid, Eliakim by Nomidis- on the northwestern cupola decorated by a central medallion of the Theotokos (Mango 1993, 425). In a similar way, in the central cupola, in a poor state of preservation, the mosaic decoration consists of the old Testament prophets, only preserved between the dome’s windows, and two palace officers, with a central medallion – possibly with the depiction of Christ that would be followed by the Prodromos on the northern dome.

Another major discovery of the 1930s excavation campaign was the revealing of eight tombs - of three were laid in the exonarthex (Mango 1993, 423). Nomidis who excavated the burials notes that six of these burials were already cleared in the time of the discovery.

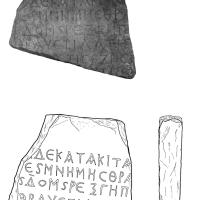

In a recent construction activity neighboring the site, an intriguing epitaph was uncovered close to the eastern limit of the katholikon. The Greek inscription on the tombstone made possible the identification of the epitaph as the tombstone of a late fifth-century Germanic general Thrasarich –the comes domesticorum, king of the Gepids- (Cetinkaya 2009, 226-7).

The overall historical survey of Vefa Kilise Camii implies that being once one of the most prominent structures of the Byzantine Constantinople, the monument deserves further architectural and archaeological focus, and needless to say, an urgent preservation plan.

VR Tour

Map Location

Bibliography

- Berger, Albrecht, Untersuchungen zu den Patria Konstantinopoleos, Ποικίλα βυζαντινά 8 (Bonn 1988): 460-461.

- Çetinkaya, Haluk, “Recent finds at Vefa kilise camii of Istanbul, Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Byzantine Studies, London 21-26 August 2006, Abstracts of Communications, II,” (London 2008).

- Brunov, Nikolai, “Über zwei byzantinische Baudenkmdler von Konstantinopel aus dem XI. Jahrhundert,” Byzantinisch-Neugriechische Jahrbucher 9 (1931-32): 139-44.

- Çetinkaya, Haluk, “An Epitaph of a Gepid Kind at Vefa Kilise Camii in Istanbul,” Revue des Études Byzantines 67 (2009): 225-229.

- Eyice, Semavi, Son Devir Bizans Mimarisi (Istanbul, 1963): 47-50.

- Freely, John and Ahmet Cakmak, Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul (Cambridge: 2004): 207.

- Kırımtayıf, S., Converted Byzantine Churches in Istanbul: Their Transformation into Mosques and Masjids (Istanbul, 2001).

- Krautheimer, Richard, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (New York, 1986): 363.

- Hafiz Hüseyin Efendi, Hadikat-ül-Cevami (Istanbul: Tercüman Aile ve Kültür Yay, 1987), 139-44.

- Hallensleben, Horst, “Zu Annexbauten der Kilise Camii in Istanbul,” IstMitt 15 (1965), 208-17.

- Janin, Raymond, La géographie ecclésiastique de L'empire Byzantin, première partie: Le siège de Constantinople et le patriarcat oecuménique, les églises et les monastères (Paris, 1969).

- Janin, Raymond, “La topographie de Constantinople byzantine: études et decouvertes, 1918-38,” EO 38 (1939): 138-39.

- Janin, Raymond, “Les églises byzantines des saints militaires,“ EO XXXIV 1935, 56-64.

- Mango, Cyril, “The Work of M.I. Nomidis in the Vefa Kilise Camii, Istanbul (1937-38),” Studies on Constantinople (Aldershot, 1993): XXII.

- Mathews, Thomas F., “Architecture et liturgie dans les premieres églises palatiales de Constantinople,” Revue de l'art 24 (1974): 22-29.

- Mathews, Thomas F., The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey (London, 1976).

- Millingen, Alexander van. Byzantine Churches in Constantinople: Their History and Architecture (London, 1912).

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang. Bildlexikon zur Topograhie Istanbuls (Tübingen, 1977).

- Πασπάτης, Αλέξανδρος, Βυζαντιναί μελέται Τοπογραφικαί και ιστορικαί (Κωνσταντινούπολης, 1877): 314-16.

- Salzenberg, W., Altchristliche Baudenkmale von Constantinopel, (Berlin 1855): 115-199, Pl. 34-35.