Christ Pantokrator Monastery

Emperor John II Komnenos (1118-43) and his wife, Eirene

1118-1136

Description

Molla Zeyrek Camii, the former katholikon of the monastery of Christ tou Pantokratoros - the Ruler of All - is located in today’s Zeyrek, a UNESCO world heritage site, renowned by its timber architecture. Situated on a steep hill bordered with a large cistern overlooking the Golden Horn, the monastic complex is one of the largest imperial institutions of the Middle and Late Byzantine Constantinople. The neighborhood is believed to house one of the largest oikos of the late antique city, named in the historical sources as tes Hilaras (Magdalino 1996: 46).

In addition to the thirteenth-century account of Niketas Choniates and the fourteenth-century anonymous of Sathas, the Typikon of the Pantokrator monastery- one of the twenty typika that survived to us from Constantinople- composed in 1136 provides us with plentiful information about the history, topography, organization and liturgy of the monastic complex that is known to house eighty male monks (Janin 1953: 529; Gautier 1974: 1). Based on its typikon, the Pantokrator complex has been originally established in the twelfth century, by the Emperor John II Komnenos, and possibly his wife Irene, the daughter of King Ladislas of Hungary in the period between 1118 and 1136 (Jordan 2000, 725). A number of historical sources such as Jean Kinnamos, Synaxarion of Nicolas the Hagiorites and Doukakes attribute the architectural patronage of the complex solely to the empress Irene Komnene (Janin 1953: 529).

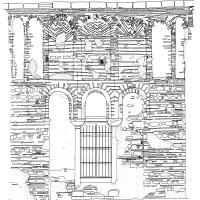

Designed by the architect Nikephoros, whose name is particularly emphasized in the historical accounts, the monastic complex is consisted of three juxtaposed churches. The south church dedicated to Christ Pantokrator that has also served as the katholikon is most likely the earliest structure of the Komnenian architectural commission, followed by a second church dedicated to the Theotokos Eleousa, constructed on the northern side of the former (Megaw 1963: 333-71). Possibly, while the construction of the Theotokos church was continuing, a smaller chapel dedicated to the Archangel Michael the Asomatos has been added to the complex (Megaw 1963: 333-71). Intended as the imperial mausoleum of the Komnenos family, refered as a heroon in the typikon, the Asomatos chapel, was completed shortly before the construction of the south courtyard and the exonarthex that enveloped the complex from south, possibly in the time of John II (Marinis 2014: 143, Ousterhout 1999: 133, 148).

Historical sources imply that the monastic complex that expanded towards west and north, is consisted of a fifty-bed hospital, an old house (gerokomeion), a leprosarium, a school of medicine, a bath and a library (Müller-Wiener 1977: 211). In addition to the monastic property largely located in Thrace, Macedonia, the Peloponnesus, the Aegean Islands and Asia Minor, the Pantokrator monastery has controlled six other monasteries in the Asian suburbs, named respectively των Νοσσιων, Μονοκαστανον, τά Άνθεμίου, του Μηδικαρίου, Galacrenes and Satyros (Janin 1953: 534).

Among the imperial family members who were buried in the Pantokrator monastery, historical sources provide the names of the empress Irene –who died in 1134-, John II Komnenos - who died during a hunt in Cilicia in 1143-, his son Manuel’s wife Irene – who died in 1158-, and finally the emperor Manuel himself in 1180 (Jordan 2000, 725).

The Pantokrator monastery housed a famous collection of Byzantine icons and relics. The icon of Saint Demetrios, the local saint of Thessaloniki, was translated from Thessalonike in 1149 under Manuel’s reign, in addition the Stone of the Unction was brought from Ephesos to the Pantokrator monastery in 1169/70 to be placed in Manuel’s tomb (Janin 1953: 530).

During the Latin occupation of Constantinople between 1204-61, largely due to its close location to the Venetian quarter on the Golden Horn, the Pantokrator monastery’s properties were given to the Venetian merchants, who gathered and enriched the monastery’s collection with further relics and icons, such as the Hodegetria icon, and the head of Saint Blasios.

On August, 15, 1261, following the reconquest of Constantinople by the Palaiologos family, the emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos celebrated his victory by parading the Hodegetria icon that was kept in the Pantokrator monastery. Under the reign of Andronikos II Palaiologos, the emperor imprisoned his opponents such as the Serbian king Stefan Uroš II Milutin (1282-1321), and Alexios Philanthropenos in the monastic complex (Jordan 2000, 726). The Pantokrator kept its imperial mausolea character in the Palaiologean period as well, as Manuel II Palaiologos and John VIII Palaiologos have been buried in the monastic complex and attracted many Russian pilgrims' attention through the fourteenth century and fifteenth centuries (Majeska 2009: 289-95).

Following the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans, the Pantokrator monastery was converted into a medrese, koranic school with the patronage of Mehmed II, who placed Zeyrek Molla Efendi in charge (Müller-Wiener 1977: 214).

VR Tour

Map Location

Bibliography

- Bees, Nikos, “Philologikai parasemeioseis tes en Konstantinoupolei mones tou Pantokratoros Christou,” EP 3 (1909), 229–39.

- Butler, Lawrence, “The Pantocrator Monastery, An Imperial Foundation,” (M.A. thesis, Oberlin College, 1980), summarized in Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin 37 (1980), 88–90.

- Codellas, P., “The Pantocrator, Imperial Byzantine Medical Center of the XIIIth Century in Constantinople,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 12 (1942), 392–410.

- Congdon, E., “Imperial Commemoration and Ritual in the Typikon of the Monastery of Christ Pantokrator,“ REB 54 (1996): 161-99.

- Çuhadaroğlu, F., "Zeyrek Kilise Camii Restitüsyon," Rölöve Restitüsyon Dergisi 1 (1974): 99-108.

- Ebersolt, Jean and A. Thiers, Les Églises de Constantinople (Paris, 1913), 171-207.

- Frolow, A., “Les noms de monnaies dans la typikon du Pantocrator,” Byzantinoslavica 10 (1949), 241–53.

- Gautier, Paul, “L’obituaire du typikon du Pantocrator,” REB 27 (1969), 235–62.

- Gautier, Paul, "Le typikon du Christ Sauveur Pantocrator," REB 32 (1974): 1-145; (and English translation by Robert Jordan in Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of Surviving Founders (Washington, 2000): 725-81).

- Hergès, Adolphe, “Le monastère du Pantocrator à Constantinople,” EO 2 (1898), 70–88.

- Janin, Raymond, La Géographie Ecclésiastique de L'empire Byzantin, Première Partie: Le siège de Constantinople et le patriarcat oecuménique, Les Églises et les monastères (Paris, 1969): 515- 23.

- Jeanselme, Edouard, “Calcul de la ration alimentaire des malades de l’hôpital et de l’asile des vieillards annexés au monastère du Pantocrator à Byzance (1136),” extract from 2e Congrès d’Histoire de la Médecine (Evreux, 1922), 10 pp.

- Jeanselme, Edouard, and Oeconomos, Lysimaque, “Les oeuvres d’assistance et les hôpitaux byzantins au siècle des Comnènes,” extract from Ier Congrès de l’histoire de l’art de Guérir (Anvers, 1921).

- Kotzabassi, Sofia, The Pantokrator Monastery in Constantinople (De Gruyter, 2013).

- Lampros, Spiros, “To prototypon tou typikou tes en Konstantinoupolei mones tou Pantokratoros,” NH 5 (1908), 392–99; rev. by Nikos Bees, Byzantis 1 (1909): 490–92.

- Magdalino, Paul, and Nelson, Robert, “The Emperor in Byzantine Art of the Twelfth Century,” BF 8 (1982), 123–83, and 126–30.

- Magdalino, Paul, Constantinople médiévale. Études sur l'évolution des structures urbaines, Travaux et Mémoires, Monographies 9 (Paris, 1996).

- Majeska, George, Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries (Washington, D.C., 1984): 289–95.

- Mango, Cyril, “Notes on Byzantine Monuments: Tomb of Manuel I Comnenus,” DOP 23–24 (1969–70): 372–75.

- Mathews, Thomas, The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey (University Park, Pa., 1976): 71–101.

- Megaw, A. H. S., “Notes on Recent Work of the Byzantine Institute in Istanbul, Zeyrek Camii,” DOP 17 (1963): 335–64.

- Miller, Timothy, The Birth of the Hospital in the Byzantine Empire (Baltimore, Md., 1985): 12–21.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Tübingen, 1978): 209-15.

- Ousterhout, Robert, "Architecture, Art, and Komnenian Ideology at the Pantokrator Monastery," in Byzantine Constantinople, Ed. by Nevra Necipoglu (Brill, 1999): 33-50.

- Ousterhout, Robert, "Contextualizing the Later Churches of Constantinople: Suggested Methodologies and a Few Examples," DOP 54 (2000): 241–50.

- Ousterhout, Robert and Zeynep& Metin Ahunbay, "Study and Restoration of the Zeyrek Camii in Istanbul: First Report, 1997-98," DOP 54 (2000): 265-270.

- Ousterhout, Robert and Zeynep& Metin Ahunbay, "Study and Restoration of the Zeyrek Camii in Istanbul: Second Report, 2001-05," DOP 63 (2009): 235-56.

- Ousterhout, Robert, “Interpreting the Construction History of the Zeyrek Camii in Istanbul (Monastery of Christ Pantokrator),” Studies in Ancient Structures. Proceedings of the Second International Conference (Istanbul, 2001), vol. I: 19-27.

- Ousterhout, Robert, “The Pantokrator Monastery and Architectural Interchanges in the Thirteenth Century,” in QuartaCrociata: Venezia – Bizanzio – Impero Latino, eds. G. Ortalli, G Ravegnani, P. Schreiner (Venice, 2006), vol. II: 749-70.

- Oeconomos, Lysimaque, La vie religieuse dans l’empire byzantin au temps des Comnènes et des Anges (Paris, 1918): 194–210.

- Orlandos, A., “He anaparastasis tou xenonos tes en Konstantinoupolei mones tou Pantokratoros,” EEBS 16 (1941): 198–207.

- Philipsborn, A., “Der Fortschritt in der Entwicklung des byzantinischen Krankenhauswesens,” BZ 54 (1961): 338–65, esp. 353–55.

- ———, “Hiera nosos und die Spezial-Anstalt des Pantokrator-Krankenhauses,” Byzantion 23 (1963): 223–30.

- Schreiber, G., “Byzantinisches und abendländisches Hospital. Zur Spitalordnung des Pantocrator und zur byzantinischen Medizin,” BZ 42 (1943), 116–49, 373–76.

- Schweinfurth, Ph., “Ein Mosaik aus der Komnenenzeit in Istanbul,” Belleten 17 (1953): 489–500.

- Schweinfurth, Ph., “Der Mosaikfussboden der komnenischen Pantokratorkirche in Istanbul,” JDAI 69 (1954): 253–60.

- Talbot, Alice-Mary, and Cutler, Anthony, “Pantocrator Monastery in Constantinople,” ODB, p. 1575.

- Taylor, Alice, “The Pantocrator Monastery in Constantinople. A Comparison of Its Remains and Its Typikon,” BSC 3 (1977), 47–8.

- Tzirakes, N. E., “Pantokratoros mone,” TEE 9 (1966), cols. 1150–55.

- Underwood, Paul A., “Notes on the Work of the Byzantine Institute in Istanbul: 1954,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 9/10 (1956): 291-300.

- Van Millingen, A., Byzantine Churches in Constantinople, Their History and Architecture (London, 1912): 219–42.

- Varzos, Konstantinos, He geneologia ton Komnenon, 2 vols. (Thessaloniki, 1984): 203–28.

- Volk, Robert, Gesundheitswesen und Wohltätigkeit im Spiegel der byzantinischen Klostertypika (Munich, 1983): 134–94.