Images

VR Tour

Notes

History

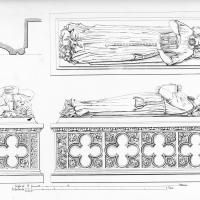

The cathedral is located in the north-east corner of the Roman cité (Civitas Cenomanorum) with the Gothic chevet breaking through the old wall. A church on the site had been established by Bishop Julien in the 4th century. A major Carolingian church was consecrated here in 834. In the 11th century Le Mans, the principal city of Maine, was controlled by the counts of Anjou: it was the center of 11th-century struggles between the Counts and the Dukes of Normandy. In 1069 the citizens expelled the Normans. A reformist bishop, Vulgrin, who had been monk at S-Serge of Angers, commenced reconstruction of the cathedral: at his death in 1065 a new chevet had been built, but it collapsed soon afterwards. His successor, Arnaud rebult the chevet and laid the foundation of a boldly-projecting new towered transept before his death in 1081. The ensuing struggle with William the Conquerer over the election of the new bishop led to an interdict and a hiatus in construction. However, the transept arms were probably in place and the lower nave begun when the church was consecrated in 1093. The nave was completed under Bishop Hildebert de Lavardin (1096-1126) under the direction of Johannes, a monk from the abbey of La Trinité, Vendôme. A crossing tower was built during the reign of Count Henri Beauclerc: the three-towered transept recalled Cluny III. Another dedication took place in 1120: the church, begun c1160, had taken sixty years to complete. Remnants of this early church survive in the outer walls of the nave and the western frontispiece; masonry from the south transept tower is embedded in the existing building. However, little is known of the form of the central vessel except in the easternmost bay where one pier on each side survives. It is to be presumed that the central vessel had a wooden roof. On September 3 1134 the city and the cathedral burned and a second fire ensued in 1137. The chevet, vaulted, was damaged but remained standing; it was necessary to rebuild the crossing and the nave main vessel. The decision to vault the nave necessitated a radical rebuild with a sturdy alternating support system. The rebuilt cathedral was dedicated in 1158. Geoffrey V of Anjou married Mathilde in the cathedral and was buried there (1151); and Henry II Plantagenet was baptized here?the site had enormous significance for the Plantagenets Angevin power came to an end in the years around 1200. The chapter at that time, made up of the elite of the province, was at the height of its powers: led by two proviseurs, Marchus and Etienne de la Chapelle, they sought permission (1217) from King Philip Augustus to demolish part of the old wall and initiated the reconstruction of the choir, considered narrow and dark. The chevet was completed between 1217 and its inauguration in 1254 when the relics of Saint Julien were transferred . In the late fourteenth century work began on the reconstruction of the transept arms; interrupted by the Hundred Years War progress was slow and the south transept tower. The construction of the transept arms belongs to the 1470s.

Date

Begun ca. 1217

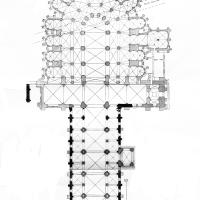

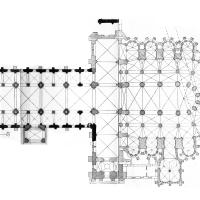

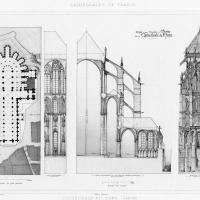

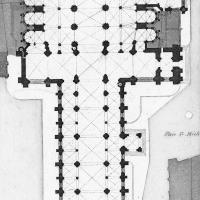

Plan

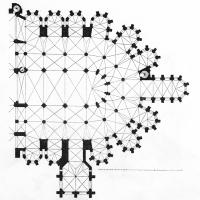

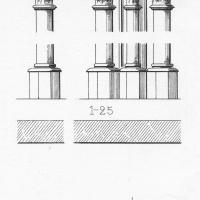

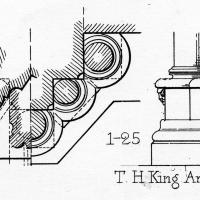

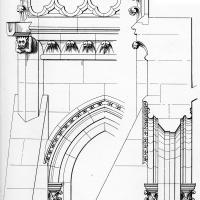

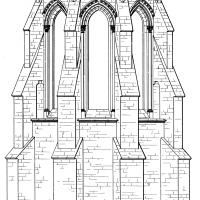

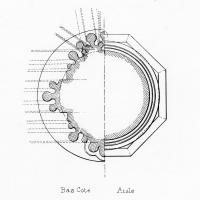

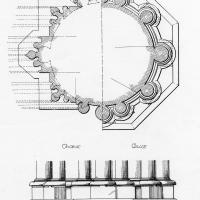

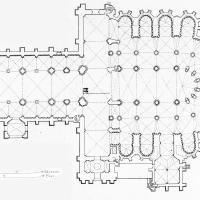

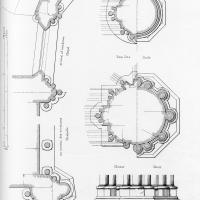

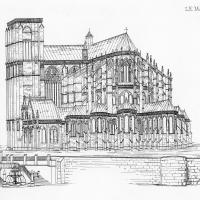

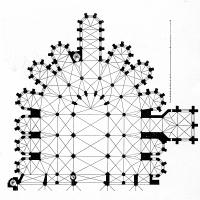

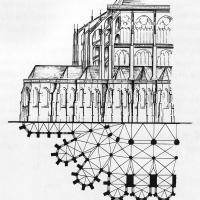

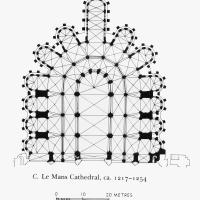

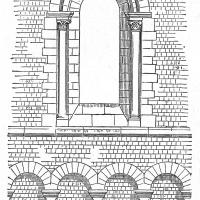

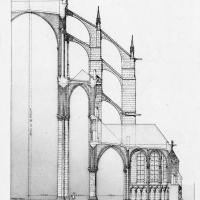

The ten bays of the aisled nave are gathered into five double bays with an alternating system of supports and square domed-up quadripartite vaults over the main vessel (the aisles are groin vaulted). On the south wall of the nave is a porch and doorway with sumptuous tympanum and column figures. From the crossing is generated a deeply-projecting aisleless square-bayed transept, the south arm with a powerful tower at its extremity. The plan of the chevet is complex: three straight bays are flanked by double aisles and terminated by a 7-segment hemicycle ringed by double ambulatories. From the outer aisles and outer ambulatory are generated deeply-projecting apsidal chapels (the axial one deeper than the others). The three chapels on each side in the straight bays are separated by massive blocks of masonry, forming substantial bases for the culées of the flying buttresses; the five chapels of the hemicycle, however, have windows between them.

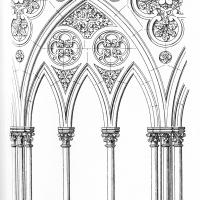

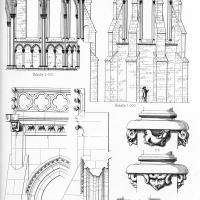

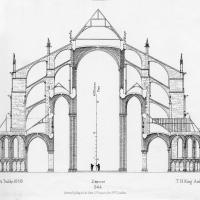

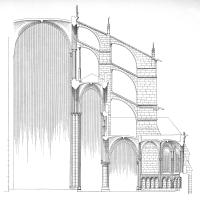

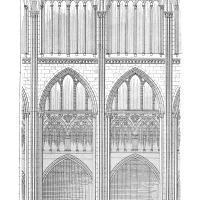

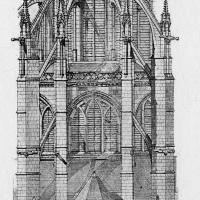

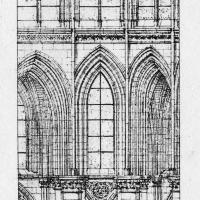

Elevation

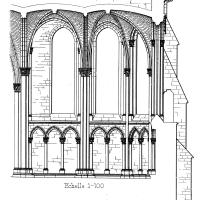

The nave has three stories with a dark triforium in the middle and paired clerstory windows. The double aisles of the chevet (inner taller than outer) create the same spatial ambiguity as at Bourges Cathedral. If we focus upon the main vessel we discover two levels (arcade and clerestory); however, if we look through the arcade to the peripheral spaces we discover (in the inner aisle) three stories (arcade, dark triforium and clerestory); then, as the eye rises to the upper level of the main vessel, the tall clerestory adds a fourth level.

Chronology

Only the chevet, constructed between 1217 and 1255 will concern us here. The work has long been considered as a three-part operation. First phase. The straight bays of the choir were laid out from west to east, surrounding the old chevet, which remained in use. Judging from the details of the work direction was in the hands of masters from Laon and the Soissonais (Braine) who had perhaps also worked at Chartres. By 1221 work was extending beyond the old city wall where it was necessary to build extensive underpinning in the form of a crypt. The windows separating the deep chapels of the hemicycle have been compared with those of S-Martin of Etampes. The first vision of the chevet was thus a conservative one?it has been argued (Bouttier) that flying buttresses were not at first intended. Second phase. A much more ambitious vision of the chevet is associated with the episcopate of Geoffroy de Loudun (1234-55) who was from a wealthy family and had been educated in Paris. The overall scheme adopted at Le Mans with a tall inner aisle makes reference to the chevet of Coutances, while the details point to Mont-Saint-Michel, Hambye, Bayeux and Dol. While the Coutances chevet is 25m in height, Le Mans is 35. Third phase. The forms of the clerestory of the main vessel (1240s-50s make reference to Parisian prototypes, particularly the work of Jean de Chelles and Pierre de Montreuil in the transept of Notre-Dame of Paris.

Sculptural Program

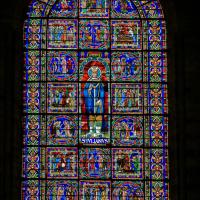

The Cathedral of Saint-Julien has a single sculpted portal, on its south transept entrance. The typical eschatological theme of the Second Coming of Christ is portrayed, with the lintel showing seated apostles under an architectural canopy, and the tympanum showing Christ seated in majesty in a mandorla, surrounded by the tetramorph (bull, eagle, man, lion). The four bands of voussoirs are historiated. The first shows angels with liturgical instruments, and the rest show scenes from the life of Christ. The jamb figures are all unidentified Old Testament kings, queens, and prophets, and flanking the door on either side are reliefs of Saints Peter (right) and Paul (left). Though these relief figures recall the reliefs in the cloister of Moissac and other earlier prototypes, the rest of the portal points very strongly to the central portal of the west façade at Chartres. Though the scenes of the life of Christ have been transferred from the capital frieze to the voussoirs, the organization of the tympanum, as well as the almost crinkled drapery and elongated forms of the column figures indicate that the Chartes' portal was central in the mind of the workshop at Le Mans. Given the official dedication of the Cathedral of Saint-Julien in 1158, and the probably completion of Chartres' west façade by about 1150, Le Mans' portal can be dated to between 1150 and 1158. However, Thomas Polk argues that there is nothing about the style of the portal that specifically prohibits it from having been created prior to Chartres, at which point it might have instead drawn inspiration from the portals of Saint-Denis. This would also indicated that the sculptures on the portal were in place prior to the addition of the porch, which is documented by 1158.

Significance

This is a building that marks the passage of local power from the counts of Anjou, to the Plantagenets, to the Capetians. The forms of the chevet, in particular, point to the different regionalisms of French Gothic: the Soissonais, Normandy and the Parisis

Location

Bibliography

Bibliography

Berranger, H. de, Un nouveau fragment des comptes de l'oeuvre de la cathédrale du Mans, Province du Maine, 1940

Bertaux, J.-J., "Saint-Julien du Mans au Coeur des pays de l'Ouest," Annales de Normandie, vol. 33:3, 1983, pp 345-347

Blin, E., Cathédrale du Mans, Sainte-Jamme, 1983

Bouttier, Michel, Cathédrale du Mans, Le Mans, 2000

----, "Le Chevet de la Cathédrale du Mans: Rechereches sur le Premier Projet," Bulletin Monumental, vol. 161:4, 2003, pp 291-306

Bregy, C., Le portail sud de la cathédrale du Mans, Geneva, 1991

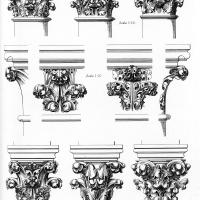

Cameron, J., "Les chapiteaux du XI siècle de la cathédrale du Mans," Bull mon, 1966

Fleury, G., La cathédrale du Mans, Paris, 1910

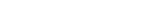

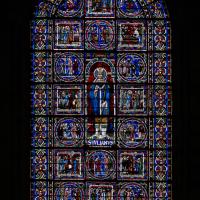

Gatouillat, F., "Les Vitraux du Bras nord du Transept de la Cathédrale du Mans et les relations Franco-Anglaises à la Fin de la Guerre de Cent Ans," Bulletin Monumental, vol. 161:4, 2003, pp 307-324

Grodecki, L., "Les vitraux de la cathédrale du Mans," Congrès archéologique, 1961

Herschamnn, J., "The Norman Ambulatory of Le Mans Cathedral and the Chevet of the Cathedral of Coutances," Gesta, 20, 1981, 323-332

Histoire du Mans et du pays manceau, Toulouse, Privat, 1975

Hucher, E. F. F., Vitraux peints de la Cathédrale du Mans; ouvrage renfermeant les reductions des plus belles verrières et la description complete de tous les vitraus de cette cathédrale, Paris, 1865

----, Calques des vitrau peints de la Cathédrale du Mans: ouvrage renfermant les calques ou les reductions, d'après les calques, des verrières de cette cathédrale les plus intéressantes sous le rapport de l'art et de l'histoire, Paris, 1864

----, Etudes artistiques et archéologiques sur le vitrail et la rose de la cathédrale du Mans, Caen, 1848

Ledru, A., La cathédrale du Mans, Paris, 1923

Lefèvre-Pontalis, E., "La cathédrale de Mans," Bull mon, 1908, 157-161

Lillich, M., Armor of Light: Stained Glass in Western France, 1250-1325 Berkeley, 1993

Mussat, A., La cathédrale du Mans, Paris, 1981

-----, Style gothique dans l'ouest de la France, Paris, 1963.

Pallu, M., Dissertation sur l'église de Saint-Julien, Cathédrale du Mans, Le Mans, 1844

Polk, T., "The South Portal of the Cathedral at Le Mans: Its Place in the Development of Early Gothic Portal Composition," Gesta, 24, 1985, 47-60.

Salet, F., "La cathédrale du Mans," Cong arch 119, 1961, 18-58

Sangster, M. B., "Envisioning Le Miracle de Théophile in France: stained glass, sculpture and stage," Medieval Perspectives, vol. 14, 1999, pp 191-201

Subes, M.-P., "Un décor peint vers 1370-1380 à la cathédrale du Mans." Bulletin Monumental, vol. 156:4, 1998, pp 413-414

Térouanne, P., "Les chapiteaux de Saint-Julien du Mans," Bulletin de la Société d'agriculture, sciences et arts de la Sarthe, vol. 71, 1967-1968, pp 25-35

Triger, R., L'ancien évéché du Mans avant la revolution et la psallette de la cathédrale, Mamers, 1912

Vaivre, J.-B. de, "Datation des vitraux du bras nord du transept de la cathédrale Saint-Julien du Mans," Bulletin Monumental, vol. 151:3, 1993, pp 497-523

Voisin, A., Notre-Dame du Mans, ou Cathédrale de Sain-Julien, origine, histoire, et description, Paris, 1866

See also:

http:www.fordham.gestaarnaldi.html- The Deeds of Bishop Arnald of Le Mans and the Le Mans Commune, 1065-1081