Site Profile

The Great Mosque of Amadiya/Amedi is located in the northern end of the citadel, just south of the former palace (now lost). The present building was erected during the last century over an earlier, ruined iteration of the prayer hall. Its minaret, which stands apart several meters from the hall, is the tallest structure in the city. It was probably constructed in the 16th century AD.

Media

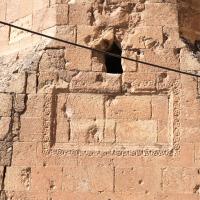

Description & Iconography

History

It has been suggested that the Great Mosque of Amadiya was built over a pre-Islamic structure, though there is no archaeological evidence for this other than the low floor level.1 Exactly when the first mosque at this site was constructed is unclear. Certainly, there was a mosque standing in Amadiya/Amedi by the Zengid period. Two items originating from this building are now preserved in the Iraq Museum: a wooden minbar datable to the 12th century and a wooden door with an inscription from the reign of Badr al-Din Lu’lu’ (1225-1259 AD).2 It may be presumed, though it cannot be definitively verified, that this medieval building stood at the site of the present Great Mosque. The minaret may have been a later addition to the mosque. Its inscription was never added, and we have no other written records ascribing its construction to a particular patron. However, local tradition holds that it was constructed under the Bahdinan emir Hussein Wali (r. 1534-1573 AD).3 The mosque was in ruins by the mid-1840s, according to the reports of Western travelers (see further in “Early Publications”). It was rebuilt in the 20th century, and its minaret was repaired after being damaged during the bombing raids of the 1960s.

Early Publications

Although earlier travelers to Amadiya/Amedi refer vaguely to a mosque, William Ainsworth and Henry James Ross—both visiting in the 1840s—provide enough detail to identify their descriptions with the precursor to the present-day Great Mosque; the latter observes: “In front of the palace were the remains of a large mosque, ruined by war and neglect; the minaret, however, was solidly built and formed a fine object.”1 Henry Binder, in the 1880s, was the only traveler who took a photograph of the monument.2

Selected Bibliography

Ainsworth, William. 1842. Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea, and Armenia. 2 vols. London: J. W. Parker.

Al-Janabi, Tariq. 1982. Studies in Mediaeval Iraqi Architecture. Baghdad: Republic of Iraq, Ministry of Culture and Information, State Organization of Antiquities and Heritage.

Binder, Henry. 1887. Au Kurdistan en Mésopotamie et en Perse. Paris: Maison Quentin.

Ross Henry James. 1902. Letters from the East by Henry James Ross, 1837-1857. London: Dent.