Site Profile

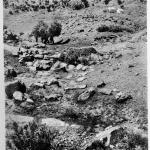

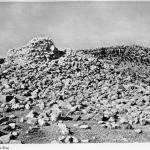

The Paikuli monument, dating to the Sasanian period, was built on a hillock just south of the eponymous pass, which traverses the Qara Dagh range of the western Zagros Mountains (see the panorama). In Sasanian times, the pass was part of a strategic route from the imperial capital of Ctesiphon into the Shahrazur plain (in which is located the modern city of Sulaymaniyah/Slemani) and farther north, the mountainous Āburbādagān province (corresponding to the northwestern region of present-day Iran, Iranian Azerbaijan); the pass itself lay near the boundary between the provinces of Garmagān (encompassing much of modern Iraqi Kurdistan) and Asōristān (the core of Mesopotamia, to which Ctesiphon belonged).1 Today, the remnants of the collapsed structure are found 16 km west of the city of Darband-i Khan and 100 km south of Sulaymaniyah/Slemani.

The monument, adorned with a lengthy inscription, was constructed by the emperor Narseh (r. 293–302 AD) to commemorate his ascent to the imperial throne. The inscription suggests that the monument was sited at the place where the nobles and grandees of the empire had gathered to meet Narseh and proclaim their support for his claim over that of his great nephew, Bahram III.

- 1. On the geographical position of Paikuli, see Cereti, Terribili, and Tilia 2015.

Media

Description & Iconography

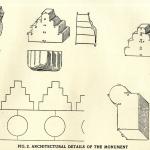

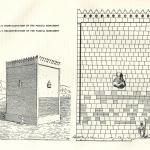

“Description and Iconography” general sources: Herzfeld 1924, 1–10; Cereti and Terribili 2012, 84–87; Terribili and Tilia 2016, 419–423.

Inscriptions

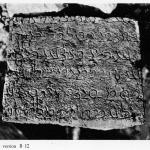

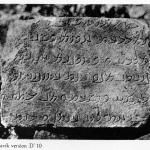

The Paikuli monument is perhaps best known for its long inscription—one of the key primary sources for the early history of the Sasanian empire. Given the inscription’s disintegration along with the collapse of the monument, its translation has posed an enormous challenge for scholars. Indeed, the process has spanned over a century, and work continues to this day. In 1844, Henry Rawlinson laid the groundwork by making drawings of 32 of the inscribed blocks; he passed the drawings on to E. Thomas, who published the first tentative transcription.1 However, it was Ernst Herzfeld who made the first systematic translation. Herzfeld analyzed the distribution of the blocks as they had fallen to suggest that there were two versions of the same inscription on either side: Middle Persian (“Pársik”) on the west, and Parthian (“Pahlavík”) on the east (see historical photographs of exemplary blocks from the west and east).

More recent scholars have confirmed that Herzfeld was also generally correct in his reconstruction of the arrangement of the inscribed blocks. The inscription’s layout covered eight courses for the Middle Persian version and 7 courses for the Parthian. The inscription is rendered in low relief; the letter size varies according to the course. The later lines on the lower courses, presumably set around eye level, are smaller (characters ca. 30–40 mm); the earlier lines, set on higher courses and thus at a greater distance from the viewer, are larger (characters ca. 50–60 mm).

There are numerous gaps in each version of the inscription—in Herzfeld’s time, roughly half of the inscribed blocks. However, it is clear that the two texts run in parallel, a correspondence that allowed Herzfeld to compensate, to some degree, for the lacunae on each side.

Herzfeld’s study was a crucial step in elucidating the inscription’s content, but scholars have made a number of revisions to his readings; moreover, new blocks have come to light—30 of them in Herzfeld’s own time—which were not included in his 1924 monograph. Many of these additions appeared in the translation of Helmut Humbach and Prods Skjærvø (1978–1983), which remains the standard reference edition. Scholars have continued to fill in the gaps as further blocks—more than 20 as of 2020—have come to light.2

The inscription provides Narseh’s account of the events by which he acceded to the Sasanian throne, along with introductory and closing passages. The following summary draws mainly on the translation of Humbach and Skjaervø:3

Narseh provides his genealogy in accordance with the conventions of Sasanian royal inscriptions, and reference is made to the raising of the monument. After this introduction, the inscription moves on to the chronicle of events leading to Narseh’s coronation. These begin with the death of Narseh’s nephew, Bahram II, and the crowning of his son, Bahram III, by the noble courtier Wahnām. Following this, an opposing faction of nobles met in council and wrote to Narseh asking him to depart from Armenia (the vassal state he had been ruling on behalf of his nephew), overthrow the usurpers, and take his legitimate place on the imperial throne.

Narseh indeed set out for Persia Ctesiphon, sending an offer of truce to Bahram and Wahnām, as well as an advance notice to the nobles that he would accept their offer. An important passage is found in line 32, narrating that as he crossed into the Persian dominions, Narseh and his adherents met at “the place where this monument has been made.” This meeting is presumably the reason why Paikuli was chosen as the site for the monument.

Meanwhile, Wahnām and Bahram enlisted the support of other notables and set out on their campaign against Narseh. Nevertheless, their troops began to desert in favor of Narseh. At this time, Narseh wrote a letter admonishing Bahram for his inappropriate seizure of the throne, and Bahram surrendered; Wahnām saw that his cause was lost and fled, but he was captured by a party sent by Narseh. Narseh also punished the larger body of rebels.

The inscription then turns back to the correspondence between Narseh and the loyal nobles over the issue of the succession. Narseh reminded them of the traditional procedure for determining who was the most suitable to be king, and the dignitaries confirmed that Narseh was indeed the most appropriate successor. Narseh was formally invited to take the throne, which he accepted.

The concluding portion of the inscription notes the state of peace and friendship with Rome before moving on to the list of kings and lesser rulers who acknowledged Narseh as King of Kings. Finally, Narseh refers to his just rule after claiming the realm anew.

A noteworthy recent addition to the translation, deriving from a recently discovered block, is an early passage that refers to the monument as “Pērōz-Anāhid-Narseh” (possibly to be read approximately as “Narseh victorious by the grace of Anāhīd”); because it is formulated as a proper name, this may even have been the name of the monument itself.4 Anahid is the same goddess who presides over Narseh’s investiture at Naqsh-i Rustam.

“Inscriptions” general sources: Humbach and Skjaervø 1983; Skjaervø 2006; Cereti and Terribili 2014.

History

Narseh, the Sasanian king responsible for the Paikuli monument, was the third son of the great emperor Shapur I (r. 242–272 AD). As a younger son, he was never expected to accede to the imperial throne but was instead assigned kingship over the important, semi-independent domain of Armenia. Upon Shapur’s death, the throne fell to Narseh’s two older brothers in succession, Hormizd I (272–273) and Bahram I (273–276), then to Bahram’s son Bahram II (276–293). Upon the latter’s death in 293 AD, his own young son and namesake was proclaimed king, as Bahram III, with the support of a court faction led by the nobleman Wahnām. However, another faction apparently opposed the coronation (at this time, the issue of royal succession seems to have been controlled in large part by the consensus of the realm’s nobles).

The events following this are known mainly from the inscription itself, an obviously biased account (see “Inscriptions”). According to Narseh’s version of the narrative, the nobles beseeched him to march from Armenia and take the throne as the legitimate king. En route towards Ctesiphon, he met with a delegation of his supporters at Paikuli—the site later chosen for the monument—before resuming his march. Bahram and Wahnām seem to have surrendered before any actual fighting broke out, as no battle is mentioned in the inscription.

It can be assumed that the monument was erected during the first few years after Narseh’s imperial accession in 293. The inscription’s final section mentions peace with the Romans, broken in 296 when Narseh declared war on Rome under Diocletian. The other major monument of Narseh’s reign is his famous investiture scene carved at Naqsh-i Rustam.

It seems likely that the Paikuli monument stood at least through the end of the Sasanian period, but its subsequent history is obscure. We can only ascertain that it had been long ruined by 1844, when Henry Rawlinson referred to its remains as “indiscriminate heaps of brick and mortar, rubble and stones.”1 Rawlinson reports that the monument was known to the local Kurdish people as a but-khaneh (“idol temple”).2

“History” general sources: Humbach and Skjaervø 1983 (3.2), 10–13; Cereti and Terribili 2012.

Early Publications

Henry Rawlinson, visiting Paikuli in 1844, made notes on the monument’s setting and condition, and drew sketches of several inscribed blocks (allowing for an early attempt at the inscription’s transliteration by E. Thomas in 1867).1 No further study was conducted until Ernst Herzfeld’s expeditions to the site in 1911 and 1913, which led to his monograph on the monument and its inscription in 1924.2 This work was accompanied by photographs of the monument and its surroundings, as well as a photographic inventory the inscribed blocks. Herzfeld visited Paikuli for a third time in 1923, discovering 30 new blocks of the inscription (too late for inclusion in his monograph of 1924).3 Although Herzfeld’s studies are crucial to our understanding of the monument, it should be noted that they did not constitute a systematic excavation of the site; indeed, such an investigation remains a desideratum to this day.

- 1. Rawlinson 1867; Rawlinson describes having heard of the monument by the 1930s, but did not actually visit the site until 1844, and his comments were only published in 1867 as an appended note within Thomas’ study of the inscription (Thomas 1867).

- 2. The preliminary report is found in Herzfeld 1914; the monograph in Herzfeld 1924.

- 3. Herzfeld 1926, 227–228. See comments on his notebook entries in Cereti and Terribili 2012, 83.

Selected Bibliography

Cereti, Carlo G., and Gianfilippo Terribili. 2012. “The Paikuli Monument.” In Sylloge Nummorum Sasanidarum, Bd. 2, edited by Michael Alram and Rika Gyselen, 74–87. Vienna: Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Cereti, Carlo G., and Gianfilippo Terribili. 2014. “The Middle Persian and Parthian Inscriptions on the Paikuli Tower: New Blocks and Preliminary Studies.” Iranica Antiqua 49: 347–412.

Cereti, Carlo G., Gianfilippo Terribili, and Alessandro Tilia. 2015. “Paikuli and Its Geographic Context.” In Studies on the Iranian World I: Before Islam, edited by Anna Krasnowolska and Renata Rusek-Kowalska, 267–278. Krakow: Jagiellonian University Press.

Colliva, Luca, and Gianfilippo Terribili. 2017. “A Forgotten Sasanian Sculpture: The Fifth Bust of Narseh from the Monument of Paikuli.” Vicino Oriente 21: 167–195.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1914. “Die Aufnahme des sasanidischen Denkmals von Paikuli.” Abhandlungen der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (1): 1–29.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1924. Paikuli: Monument and Inscription of the Early History of the Sasanian Empire. Berlin: D. Reimer & E. Vohsen.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1926. “Reisebericht.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (n.F.) 80: 225–284.

Humbach, Helmut, and Prods O. Skjaervø. 1978–1983. The Sassanian Inscription of Paikuli. 3 vols. Wiesbaden: Dr. L. R. Reichert; Tehran: Iranian Culture Foundation.

Rawlinson, Henry. 1867. “Note on the Locality and Surroundings of Paikuli.” In by E. Thomas, “Sassanian Inscriptions,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (n.s.) 3 (1): 296–300.

Skjaervø, Prods O. 2006. “A New Block from the Paikuli Inscription.” Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology 1: 119–123.

Terribili, Gianfilippo, and Alessandro Tilia. 2016. “The Activities of the Italian Archaeological Mission in Iraqi Kurdistan (MAIKI): The Survey Area and the New Evidence from Paikuli Blocks Documentation.” In The Archaeology of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and Adjacent Regions, edited by Konstantinos Kopanias and John MacGinnis, 417–425. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Thomas, E. 1868. “Sassanian Inscriptions.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (n.s.) 3 (1): 241–358.