Site Profile

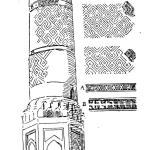

The Choli Minaret, also known as the Mudhafaria Minaret, is located in the city of Erbil/Hawler. It stands about 1 km west/southwest of the city’s central citadel, one of the oldest inhabited settlements in the world. Originally, the minaret was part of a larger architectural complex. The surrounding buildings have completely disappeared, and the leaning minaret is the only surviving element (now located in a public garden; see the panorama). It is said to have been built by the ruler Muzzafar al-Din Gokburi (r. 1168–1233 AD), last of the region’s Begteginid dynasts. It is the only preserved medieval architectural monument still standing above ground in present-day Erbil/Hawler.

Media

Description & Iconography

Inscriptions

A horizontal band near the top of the minaret’s base originally bore an inscription rendered in brick mosaic; however, only the mortar impressions of the interlaced Kufic letters—now illegible—remained by the time of the minaret’s first systematic documentation.1 A small panel has been identified over the west door, providing the name of the minaret’s architect: ‘Amal al-Hājjī Mas‘ūd ibn Abī Sa‘d (“the work of al-Hājjī Mas‘ūd ibn Abī Sa‘d”).2

History

The minaret was obviously associated with a mosque or a complex with a mosque, though the precise identification of the structure is unclear. It was largely lost by the time of European travel accounts written in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The travelers report of ruins, which they assume to be a mosque, but which are no longer extant;1 additionally, local tradition held that the minaret was associated with the al-Jāmi‘ al-‘Atīq (“ancient mosque”) known from literary sources.2 However, since Ernst Herzfeld’s study of the minaret in 1920, it has been assumed to have belonged to a mosque-madrassa complex built during the reign of Muzzafar al-Din Gokburi, atabeg of Erbil during the reign of Saladin.3

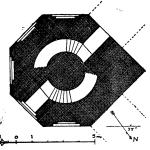

Archaeological excavations conducted by the Iraqi Directorate of Antiquities in the 1960s recovered the foundations of multiple buildings in the vicinity of the minaret, including a mosque to the southeast, of an earlier (Umayyad or Abbasid) date.4 This has led to the suggestion that the minaret—which belongs to the Begteginid period on the basis of style—was a later addition. On the other hand, foundations of an approximately contemporaneously structure join the minaret at its northwest.5 This could indicate the minaret was indeed part of a unitary madrassa complex built under Muzzafar, in keeping with Herzfeld’s proposal. However, further archaeological investigation of the foundations would be required for any firm conclusions to be drawn.

The minaret’s moniker, Choli, means “empty land.” The name is owing to the fact that in Erbil’s post-atabeg period, the lower town shrank and the minaret became isolated from the main area of settlement, to the east. As the lower town expanded through the 20th century, the minaret was reabsorbed into Erbil’s urban fabric. It was restored in the 1960s, at which time the gallery parapet was modified to its current form. In the early 2000s, the surrounding area was landscaped into a park. By this time, the minaret’s shaft was tilting 65 cm off axis and was in danger of collapsing; in 2006, a major conservation project was begun, lasting until 2012.6

- 1. See esp. Rich 1836 (2), 15–16, 293–295; Hay 1921, 118.

- 2. Nováček et al. 2013, 11.

- 3. Herzfeld 1920, 317–318. For historical and art historical reasons, Herzfeld narrows his proposed date to the early part of Muzaffar’s reign, around 1190. His madrassa is mentioned by Ibn al-Mustawfi, Ibn Khallikan, and Ibn al-Saccar. For contemporaneous comparanda, see Creswell 1926.

- 4. Husayn 1962; al-Janabi 1983, 53. See further in Nováček et al. 2013, n. 30.

- 5. Nováček et al. 2013, 20–23 and fig. 7.

- 6. On the state of the monument at the beginning of the restoration, see Pavelka et al. 2007. For a summary of the conservation works performed, see GEMA Art Group (web page), “Minaret Choli in Erbil, Iraq,” accessed August 4, 2020, https://www.gemaart.com/en/minaret-choli-in-erbil-iraq/. See also Justa and Housta 2010. On related excavations and digital documentation, see Nováček et al. 2008, 293–296.

Early Publications

Numerous travelers visiting Erbil from the late 18th–early 20th centuries made note of the minaret.1 For instance, James S. Buckingham—who passed through the area in 1816—observes: “On going out of the town to the southward, we noticed a fine tall minaret, now isolated, and in ruins, though the green tile-facing of its original exterior was still visible in many places, and from its size and style of ornament, it must have been attached to some considerable mosque.”2 Until the 1920s, these reports also indicate that ruins were visible in the vicinity. A number of travelers included interpretations of the minaret and surrounding ruins in their sketches of the citadel (see Claudius Rich’s drawing; see Eugène Flandin's drawing). In his more scholarly 1920 publication, Ernst Herzfeld provided detailed plans, diagrams, and photographs of the monument.3

Research into the structures surrounding the minaret began with archaeological excavations conducted by the Iraqi Directorate of Antiquities in the 1960s.4

Selected Bibliography

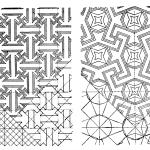

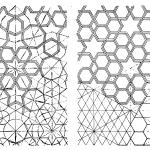

Al Ajlouni, Rima, and Petr Justa. 2011. “Reconstruction of Eroded and Visually Complicated Archaeological Geometric Patterns: Minaret Choli, Iraq.” Geoinformatics FCE CTU 6 (Reviewed Papers from XXIIIrd International CIPA Symposium, Prague, Czech Republic, September 12-16, 2011): 18–24.

Al-Janabi, Tariq. 1983. Studies in Mediaeval Iraqi Architecture. Baghdad: Ministry of Culture and Information. [Arabic version: Al-Janabi, Tariq. 1982. Dirāsāt fī al-ʻimārah al-ʻIrāqīyah fī al-ʻuṣūr al-wusṭá. Baghdad: Wizārat al-Thaqāfah wa-al-Iʻlām.]

Buckingham, James S. 1827. Travels in Mesopotamia. London: H. Colburn.

Creswell, K. A. C. 1926. “The Evolution of the Minaret, with Special Reference to Egypt-III.” Burlington Magazine 48 (278): 290–292+294–298.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1920. “Sindjār.” In Archäologische Reise im Euphrat- und Tigris-Gebiet, vol. 2, by Friedrich Sarre and Ernst Herzfeld, 305-348. Berlin: D. Riemer.

Hay, William R. 1921. Two Years in Kurdistan Experiences of a Persian Officer, 1918–1920. London: Sidgwick & Jackson.

Husayn, K. 1962. “Al-Tanqīb hawla al-mi’dhana al-muzaffarīya fī Arbīl.” Sumer 18: 205–207 (in Arabic).

Justa, Petr, and Miroslav Houska. 2010. “The Conservation of Minaret Choli, Erbil, Iraq.” Conservation and the Eastern Mediterranean: Contributions to the 2010 IIC Congress, Istanbul, edited by Christina Rozeik, Ashok Roy, and David Saunders, 255. London: International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works.

Lehmann-Haupt, Carl. 1926. Armenien, einst und jetzt, vol. 2 (2). Berlin: B. Behr.

Pavelka, Karen L., Jirina Svatušková, and Veronika Králová. 2007. “Photogrammetric Documentation and Visualization of Choli Minaret and Great Citadel in Erbil/Iraq.” In Proceedings of the 21st CIPA Symposium: AntiCIPAting the Future of the Cultural Past (ISPRS Archives, Vol. 36-5/C53), 245–258. Athens: CIPA.

Nováček, Karel, Narmin Ali Muhammad Amin, and Miroslav Melčák. 2013. “A Medieval City within Assyrian Walls: The Continuity of the Town of Arbīl in Northern Mesopotamia.” Iraq 75: 1–42.

Rich, Claudius. 1836. Narrative of a Residence in Koordistan […]. London: J. Duncan.

Streck, M. 1927. “Irbil.” In The Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1st ed., vol. 4: 521–523. Leiden: Brill.