Site Profile

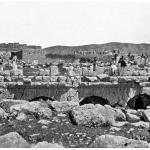

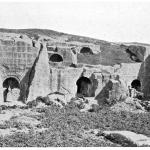

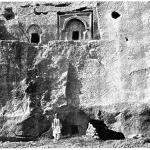

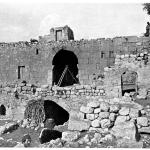

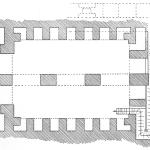

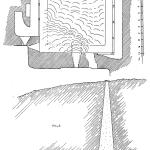

The archaeological site of Dara is integrated with the modern village of Oğuz in the Mardin Province of Turkey, 23 km southeast of the city of Mardin. In the early 6th century AD, the small hamlet at this location was transformed into a major Roman outpost against the Sasanian Empire—lying just 18 km northwest of the contested city of Nisibis (Nusaybin)—and renamed Anastasiopolis after the reigning emperor. The site, near the boundary between the Tur ‘Abdin mountain to the north and the Mesopotamian plain to the south, was chosen for its natural defensive position and access to a small tributary of the Habur, the Cordes River, which bisected the city. With its relatively short phase of building activity, the archaeological site provides a unique snapshot of a frontier settlement of the Late Roman/Early Byzantine period. Significant surviving features include stretches of the city massive fortification walls, a large cistern, and a rock-cut necropolis.

Media

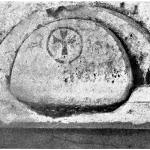

Description & Iconography

On Dara's layout and monuments, see also: Preusser 1911, 44–49; Crow 1981; Croke and Crow 1983, 151–156; Bell and Mundell Mango 1982, 102–105; Whitby 1986; Zanini 2003; Keser-Kayaalp et al. 2017.

History

Prior to Late Antiquity, Dara was a small village apparently founded during the Parthian period; according to Procopius and others, its transformation began in 505 AD, when it was chosen by the emperor Anastasius to serve as a Roman outpost near the border with the Sasanian Empire.1 The founding of a fortified city in this area was necessitated by the recent capture of Amida (Diyarbakır); a new base was required for Roman military operations in Mesopotamia, especially the ongoing campaign for nearby Nisibis (Nusaybin). Dara was strategically sited in relation to the surrounding mountain ranges and had access to an unfailing water source, among other advantageous features.

The city’s construction was supervised by the bishop Thomas of Amida and the Roman official Calliopius, quartermaster of the eastern army. The Roman-Sasanian treaty of 441 had forbidden the building of new fortresses in the Mesopotamian border region, but the Sasanians were occupied with other problems and could not wage a concerted campaign of retaliation; they only managed to harass the builders. Construction was rapid and the city was ready for occupation by the end of 507. During its early years, it was called Anastasiopolis after its founder.

By Justinian’s time, Dara—no longer called Anastasiopolis—had been granted the title of metropolis, becoming the headquarters of both the dux and the bishop of the province of South Mesopotamia. Dara successfully resisted a Sasanian siege in 530, the same year that the Roman general Belisarius won a great battle in the vicinity. It was at this time that the city was refortified by Justinian, who heightened the walls laid out under Anastasius. Dara continued to hold out against further attacks. However, the city was captured during the Sasanian campaign of 573, and a number of residents were exiled to the territory of the Sasanian Empire at this time. Over the next several decades, it seesawed back and forth between Sasanian and Roman control (in 591, notably, it was returned to the Romans, and the aforementioned exiles were allowed to return).

In 639, Dara was taken by the Arab-Islamic armies along with the entirety of Roman Mesopotamia. Following this, the city declined in importance, and there was little building activity. Still, it retained a sizable Syriac Orthodox community through at least the 13th century (as attested by ecclesiastical records), and it maintained a multi-ethnic population into the following centuries. After his visit to the site in 1842, George Percy Badger reported: “There are two villages standing amidst the ruins of ancient Dara, one containing 40 Armenian, and the other 100 Coordish families. The Christians have a small church and a priest, and are reckoned as belonging to the diocese of Diarbekir.”2 Other travelers throughout the 19th and early 20th century made frequent note of the inhabitation of the tombs and other ruins by the locals. Today, the necropolis has been converted into an archaeological park, while a village with a predominantly Kurdish population (modern Oğuz, with several hundred residents) lives on within the walls of the ancient city.

- 1. Procopius accompanied Belisarius to Dara in 529/530 and wrote about it in Buildings (2.i.4-3.26); see also Wars (2.xiii.16-19). He is suspected to have exaggerated the evidence for Justinian’s role in the city’s foundation due to the panegyrical nature of his work (see Croke and Crow 1983). See further the history of Zachariah of Mityline (ps.-Zach. Chron. vi.6); the Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite (ed. Wright 1882, 70).

- 2. Badger 1852 (1), 308. The village’s last remaining Christians departed for Syria during World War I (see Anschütz 1975, 185).

General sources on Dara’s history: Preusser 1911, 44; Anschütz 1975, 185; Croke and Crow 1983, 148–153; Keser-Kayaalp et al. 2017.

Early Publications

The first traveler to record his visit to Dara was the French adventurer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who passed through in 1644. His brief commentary focuses on the underground cistern, which he assumes to be a subterranean church.1 In 1813–1814, John Macdonald Kinneir made a systematic survey of the site, describing the necropolis, walls, and several buildings interspersed with the modern village.2 From this time, Dara was increasingly on the itinerary of travelers passing between Mardin and Mosul, who were often attracted by the city’s significant role in Roman history (a role that had been underlined by Edward Gibbon in his widely read Decline and Fall).3 It is thus mentioned in numerous 19th century travel accounts; for instance, William Ainsworth describes it as “the most remarkable place in this part of the world, whether from the extent of its ruins, its vast subterranean dwellings, and the richly ornamented decoration of its excavated tombs.”4 In the early 20th century, Conrad Preusser and Gertrude Bell more thoroughly documented the site, providing photographic surveys of its major monuments.5

- 1. Tavernier 1676, 170 (referring to the site as Karasera).

- 2. Kinneir 1818, 436–441.

- 3. Gibbon 1905 [1788], 209–210.

- 4. Ainsworth 1842 (2), 117-118; cf. Badger 1852 (1), 306–310.

- 5. Preusser 1911, 44–49, pls. 53–61; Bell’s photographs are published in Bell and Mundell Mango 1982, 102–105, pls. 1–8.

Selected Bibliography

Ainsworth, William Francis. 1842. Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea and Armenia. 2 vols. London: J. W. Parker.

Anschütz, Helga. 1975. “Einige Ortschaften des Tur ‘Abdin im sudösten der Türkei als Beispiele gegenwärtiger und historischer Bedeutung.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Suppl. 3 (1): 179–193.

Badger, George Percy. 1852. The Nestorians and Their Rituals. 2 vols. London: J. Masters.

Bell, Gertrude, and Marlia Mundell Mango. 1982. The Churches and Monasteries of the Tur ‘Abdin. London: Pindar. Reprint, with new preface, notes, and catalogues, of Gertrude Bell’s The Churches and Monasteries of the Tur ‘Abdin (1910) and Churches and Monasteries the Tur ‘Abdin and Neighboring Districts (1913).

Croke, Brian, and James Crow. 1983. “Procopius and Dara.” Journal of Roman Studies 73: 143–159.

Crow, James. 1981. “Dara, a Late Roman Fortress in Mesopotamia.” Yayla: Report of the Northern Society for Anatolian Archaeology 4: 12–20.

Furlan, Italo. 1988. “Oikema katagheion: Una problematica struttura a Dara.” In Milion: Studi e ricerche d'arte bizantina; Atti della Giornata di Studio, Roma, 4 dicembre 1986, edited by Claudia Barsanti, Alessandra G. Guidobaldi, and Antonio Iacobini, 105–118.

Gibbon, Edward. 1905 [1788]. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. 4. London: Methuen.

Keser-Kayaalp, Elif, Nihat Erdogan, and Andrew Palmer. 2017. “Recent Research on Dara/Anastasiopolis.” In New Cities in Late Antiquity: Documents and Archaeology, edited by Efthymios Rizos, 153–175. Turnhout: Brepols.

Kinneir, John Macdonald. 1818. Journey through Asia Minor, Armenia, and Koordistan in the Years 1813 and 1814. London: J. Murray.

Mundell, Marlia. 1975. “A Sixth Century Funerary Relief at Dara in Mesopotamia.” Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik 24: 209–227.

Nicholson, Oliver. 1985. “Two Notes on Dara.” American Journal of Archaeology 89 (4): 663–671.

Preusser, Conrad. 1911. Nordmesopotamische Baudenkmäler altchristlicher und islamischer Zeit. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 17. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste. 1676. Les six voyages de Jean Baptiste Tavernier, ecuyer baron d’Aubonne, en Turquie, en Perse, et aux Indes […]. Vol. 1. Paris: G. Clouzier and C. Barbin.

Whitby, M. 1986. “Procopius’ Description of Dara ('Buildings' II.1-3).” In The Defence of the Roman and Byzantine East: Proceedings of a Colloquium Held at the University of Sheffield in April 1986, edited by Philip Freeman and David Kennedy, 737–783. Oxford: B.A.R.

Zanini, Enrico. 2003. “The Urban Ideal and Urban Planning in Byzantine Cities of the Sixth Century AD.” In Theory and Practice in Late Antique Archaeology, edited by Luke Lavan and William Bowden, 196–223. Leiden: Brill.