Site Profile

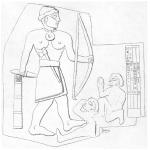

The Darband-i Balula relief is found to the east of the modern village of Balula, near the Iranian border about 80 km southeast of Sulaymaniyah. The village lies just below the westernmost range of the Zagros, the Qara Dagh; more specifically, it is located along the Abbasan/Hawwasan River, a tributary of the Diyala, at the point where it joined by a stream that descends from Mt. Bamo to the east. The gorge that has been carved by this stream provides a mountain pass, and the relief—with an accompanying cuneiform inscription—is rendered on a protruding rock formation high up on its cliffside (see the panorama). Dating to the early second millennium BC (Old Babylonian period), it depicts an armed male figure standing triumphantly over two smaller victims.

Media

Description & Iconography

“Description & Iconography” general sources: Berger 1892; Herzfeld 1941, 186–187; Debevoise 1942, 81–82; Calmeyer 1975; Börker-Klähn 1982, 139–140 (no. 33); Postgate and Roaf 1997.

Inscriptions

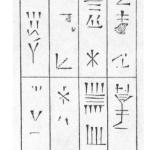

The inscription is both damaged and difficult to translate, and no standard reading is agreed for its entirety (see the drawing).1 The first row refers to the lineage of a ruler whose name is no longer legible. The second row describes his creation of an image and places a curse on anyone who should harm it. The third row seems to continue the curse, invoking the gods Shamash and Adad. The characters appear to date to the Old Babylonian period, with some archaisms and some more up-to-date forms.2

- 1. See the overviews in Calmeyer 1975; Farber 1975; Börker-Klähn 1982, 139–140 (no. 33); Postgate and Roaf 1997, 146–148.

- 2. Herzfeld (1941, 186) suggested that the inscription was added to the relief at a date subsequent to its creation; this has been rejected by later scholars (see the preceding note).

History

The inscription accompanying the Darband-i Balula relief preserves only hints of the name of the ruler responsible for it, and this does not allow for his identification with any known historical individual. The small size of the relief, as well as its provincial style, would seem to indicate a local rather than imperial ruler or commission.1

The purpose of the relief is also unclear. The theme certainly lends itself the commemoration of a military victory, but in the absence of historical evidence, its particular significance remains elusive.2 Its position in the landscape raises tantalizing questions about its function. While it is sited along a mountain pass, it is doubtful that this was a significant thoroughfare; moreover, the relief’s relatively small size, set at such a soaring height, renders it (and especially its accompanying inscription) barely legible to would-be passers-by. A number of Near Eastern reliefs are comparably sited, suggesting that their visibility to human eyes was not a primary concern.

Early Publications

Passing through the site in 1836, Henry Rawlinson published a brief commentary of the Darband-i Balula (“Sheikhan”) relief shortly thereafter, comparing the composition to the victorious ruler motif commonly found on cylinder seals and making a summary note of the cuneiform inscription.1 A close examination and drawings of the relief and inscription were made by Léon Berger in 1890; another such study was conducted by Jacques de Morgan and Vincent Scheil the following year.2 In 1923, Ernst Herzfeld paid a visit and marked the position of the relief in his 1924 archaeological map of the region.3 Cecil J. Edmonds, an officer in the British administration of Iraq, studied the site in 1926 and published early photographic documentation of the relief (see the historical photograph).4

Selected Bibliography

Berger, Léon. 1892. “Sculpture rupestre de Chéïkh-khân.” Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 2 (4): 115–120.

Börker-Klähn, Jutta. 1982. Altvorderasiatische Bildstelen und vergleichbare Felsreliefs. Baghdader Forschungen 4. Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern.

Calmeyer, P. 1975. “Hūrīn Šaihān.” In Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie, edited by Dietz Otto Edzard, et al. Vol. 4: 504–505.

De Morgan, Jacques, and Vincent Scheil. 1893. “Les deux stèles de Zohâb.” Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l'archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes 14: 100–105.

Debevoise, Neilson C. 1942. “The Rock Reliefs of Ancient Iran.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 1 (1): 76–105.

Edmonds, Cecil J. 1928. “Two More Ancient Monuments in Southern Kurdistan.” Geographical Journal 72 (2): 162–163.

Edmonds, Cecil J. 1966. “Some Ancient Monuments on the Iraqi-Persian Boundary.” Iraq 28 (2): 159–163.

Farber, Walter. 1975. “Zur Datierung der Felsinschrift von Šaih-hān.” Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran (n.F.) 8: 47–50.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1924. Paikuli: Monument and Inscription of the Early History of the Sasanian Empire. Berlin: D. Reimer & E. Vohsen.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1926. “Reisebericht.” Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft (n.F.) 80: 225–284.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1941. Iran in the Ancient East. London: Oxford University Press.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1968. The Persian Empire: Studies in Geography and Ethnography of the Ancient Near East. Wiesbaden: F. Steiner.

Postgate, J. Nicholas, and Michael D. Roaf. 1997. “The Shaikhan Relief.” Al Rāfidān 18: 143–156.

Rawlinson, Henry. 1939. “Notes on a March from Zoháb, at the Foot of Zagros, along the Mountains to Khúzistán (Susiana), and from Thence through the Province of Luristan to Kirmánsháh, in the Year 1836.” Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London 9: 26–116.