Site Profile

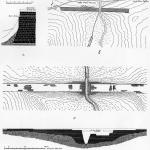

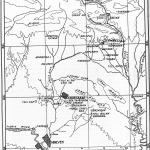

The Jerwan Aqueduct is probably the world’s oldest known aqueduct. It is located north of Nineveh, opposite to the modern city of Mosul in Iraq. Built by the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC), the aqueduct was highly advanced in its engineering and construction. It carried water across a ravine as a part of the hydraulic system that Sennacherib built to provide water to his capital city of Nineveh.

Media

Description & Iconography

'Description & Iconography' general sources: Bachmann 1927; Jacobsen and Lloyd 1935, 6–18.

Inscriptions

Several cuneiform inscriptions were recovered at the site of the aqueduct. Some of these are original to the site and were found in situ, while others were reused from other buildings.

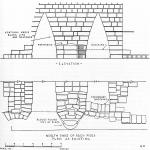

- Inscription A is the shortest of the inscriptions found here. Its text reads: “Belonging to Sennacherib, king of the world, king of Assyria.”1 Inscription A corresponds to the type of brick inscriptions found in Assyrian and Babylonian buildings. From the content of these inscriptions and their typical location within the fabric of the masonry, it seems likely that they were not intended to be read until the building had fallen into ruin.

- Inscription B is the standard inscription of the aqueduct, recording Sennacherib's drawing of water from various rivers and mountains and establishing a bridge of white stone blocks upon which he caused water to pass.2 The inscription was carved in multiple places on the structure, especially on its north side; it appears on every buttress and in every recess, as well as on each breakwater (as is evident from the surviving portion). Because the inscription was intended to be visible, the signs are large and carefully executed.

- Inscription C is an abbreviated version of the standard inscription above.3 Like Inscription A, the inscription’s location indicate that it must have been completely covered when the structure was intact and in use.

- Inscription D comprises a group of inscribed stones, probably reused from other buildings, that were added to the structure when the aqueduct's southern facade of the aqueduct was strengthened with a new shell of masonry (occurring at an unknown date). These inscriptions, unconnected to one another, are poorly preserved, but several fragments have been transcribed.4

- 1. Jacobsen and Lloyd 1935, 19.

- 2. For the text, see 'Sennacherib 226' at: http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/rinap/rinap3/corpus/

- 3. For the text, see 'Sennacherib 227' at: http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/rinap/rinap3/corpus/

- 4. For the text, see 'Sennacherib 228' at: http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/rinap/rinap3/corpus/

'Inscriptions' general sources: Jacobsen and Lloyd 1935, 19–30; Grayson and Novotny 2014, 317–326 (nos. 224–228).

History

As confirmed by Sennacherib's inscriptions, the aqueduct was constructed to supply Nineveh and its surroundings with water. It was a part of the so-called Khinnis system, which began at a weir across the Gomel River to the north.

After the aqueduct had fallen into ruins, a small village called Jerwan was built atop the structure's southern portion, to the east of the arches; the village is now gone. The present archaeological site stands as a testament to the world's oldest known aqueduct.

Early Publications

Austen Henry Layard visited Jerwan in the mid-19th century and described the aqueduct.1 Several other early travelers and archaeologists also visited the site, including L. W. King, who stopped and photographed it on his way to Khinnis in 1904.2 Both Layard and King thought that the ruins were the remains of a road. However, King rightly assigned the ruins to Sennacherib on the basis of inscriptions that he found in the village of Mahad, about 3 miles southeast of Jerwan. In addition to King, A. T. Olmstead apparently passed through Jerwan, describing it as a 'raised stone track along which went the canal.”3 Walter Bachmann systematically surveyed the site in 1914 and recorded the ruins without actually digging.4 In the decades after World War I, several travelers and scholars visited the site, and in the 1930s, the general outline of the aqueduct and the canal’s route was established through archaeological excavations conducted by Seton Lloyd and Thorkild Jacobsen.5

Selected Bibliography

Bachmann, Walter. 1927. Felsreliefs in Assyria, Bawian, Maltai und Gundük. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 52. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

Boehmer, R. M. 1997. “Bemerkungen bzw. Ergänzungen zu Gerwan, Khinis, und Faidhi.” Baghdader Mitteilungen 28: 245–249.

Grayson, A. Kirk, and Jamie Novotny, eds. 2014. The Royal Inscriptions of Sennacherib, King of Assyria (704–681 BC). Vol. 2. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Jacobsen, Thorkild, and Seton Lloyd. 1935. Sennacherib’s Aqueduct at Jerwan. Chicago: Oriental Institute Publications.

Layard, Austen Henry. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. London: J. Murray, 1853.

Olmstead, A. T. 1923. History of Assyria. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

Reade, Julian E. 1978. “Studies in Assyrian Geography I: Sennacherib and the Waters of Nineveh.” Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 73: 47–72.

Ur, Jason. 2005. “Sennacherib’s Northern Assyrian Canals: New Insights from Imagery and Aerial Photography.” Iraq 67: 317–345.