Site Profile

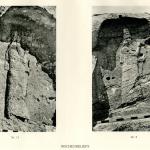

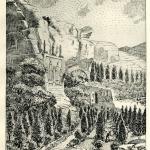

The complex of Khinnis, ancient Khunusa, is located about 60 km northeast of Mosul near the village of Khinnis in present-day Iraq, where the Gomel River flows through a gorge. According to the site's cuneiform inscriptions, this massive complex was created by the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib (704–681 BC) at the head of the northeast canal that supplied water to Nineveh and surroundings. The reliefs—including the main panel, gate monument, rider relief, and stelae reliefs—are carved on the side of a narrow cliff face on the right bank of the Gomel. The modern name of the river echoes the ancient Greek name Gaugamela, south of Khinnis, where the famous battle took place.

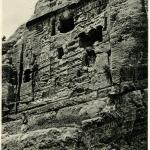

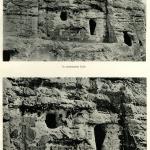

In addition to the Assyrian reliefs, several later tombs were dug into the face of the cliff at Khinnis, in some cases damaging the original reliefs.

Media

Description & Iconography

'Description & Iconography' general sources: Layard 1853, 207–216; Bachmann 1927, 1–22; Reade and Anderson 2013, 97–122.

Inscriptions

At least three of the rock-cut stelae bear inscriptions: nos. 4, 7, and 11. While no. 4 is accessible from the foot of the cliff, the other two are higher in the cliff and thus invisible from below. Although all three are damaged, they appear to have borne similar inscriptions, allowing scholars to restore the text to some extent.

These so-called 'Bavian inscriptions' first describe the accomplishments of the four hydraulic systems of Sennacherib, and in particular tell about the construction of the northeast system and the sculpted monuments that adorned it; they then report about the flooding of Babylon and its devastation in 689 BC.

'Inscriptions' general sources: Grayson and Novotny 2014, 310–317 (no. 223); see also 'Sennacherib 223' (http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/rinap/rinap3/corpus/).

History

During the Neo-Assyrian period, the monumental complex at Khinnis was an important political, religious, and spiritual site. The position of the reliefs in the steep rock directly over the water appears to be more closely related to the setting at the head of the canal rather than to visibility, suggesting that the monument should be considered according to its religious context. The king's worship of the deities, thematized throughout the reliefs of this grandiose monument, suggests the celebration of his control over water sources and the possession of the natural landscape.

In the post-Assyrian period, the site appears to have remained an important political and religious spot. During the Parthian/Sasanian period, new reliefs were carved into and near by the Assyrian panels. Furthermore, the site was used as a burial place, where later tombs were dug into the Assyrian panels damaging the original reliefs. It is plausible that these tombs were then used as monastic cells during the fourth and fifth centuries AD, thus carrying with the sacred and religious nature of the Assyrian site.

Today, Khinnis is a famous cultural and natural site of importance to both scholars and local communities. The Assyrian people of Iraq view the Khinnis complex as a part of their historical identity and culture.

Early Publications

Among the early travelers to describe the site of Khinnis was Austen Henry Layard, who visited in the mid-19th century.1 At this time, Layard drew the reliefs, copied the inscriptions, inspected the later tombs, and conducted some “excavations” near the entrance of the gorge and in other parts of the narrow valley. He recovered the remains and foundations of stone structures from under the thick mud disposed by the Gomel River. Higher up the gorge, he also noted 'the fountain,' a series of basins cut in the rock and descending in steps to the stream. In addition to Layard, T. S. Bell—an artist sent by the Trustees of the British Museum and who drowned in the Gomel—visited the site in 1851, providing drawings of the Rider Relief. In 1905, L. W. King photographed the monuments at Khinnis after clearing some vegetation. In 1909, the site was visited by Gertrude Bell, whose photos show more vegetation flourishing. Walter Bachmann studied and photographed the Khinnis complex in 1914, publishing his results in 1927.2

Selected Bibliography

Bachmann, W. 1927. Felsreliefs in Assyria, Bawian, Maltai und Gundük. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 52. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs.

Bell, Gertrude. 1911. Amurath to Amurath. London: Dutton.

Boehmer, R. D. 1997. “Bemerkungen bzw. Ergänzungen zu Gerwan, Khinis, und Faidhi.” Baghdader Mitteilungen 28: 245–249.

Grayson, A. Kirk, and Jamie Novotny, eds. 2014. The Royal Inscriptions of Sennacherib, King of Assyria (704–681 BC). Vol. 2. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

Jacobsen, Thorkild, and Seton Lloyd. 1935. Sennacherib’s Aqueduct at Jerwan. Chicago: Oriental Institute Publications.

Hallo, William W. 2003. The Context of Scripture. Vol. 2, Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World. Leiden: Brill.

Layard, Austen Henry. 1853. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon. New York: G. P. Putnam.

Reade, Julian E. 1977. “Shikaft-I Gugul: Its Date and Symbolism.” Iranica Antiqua 12: 33–44.

Reade, Julian E. 1978. “Studies in Assyrian Geography I: Sennacherib and the Waters of Nineveh.” Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 73: 47–72.

Reade, Julian E., and Julie R. Anderson. 2013. “Gunduk, Khanes, Gaugamela, Gali Zardak - Notes on Navkur and Nearby Rock-Cut Sculptures in Kurdistan.” Zeitschrift fűr Assyriologie 103: 69–123.