Site Profile

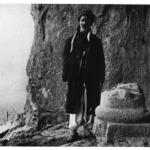

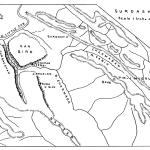

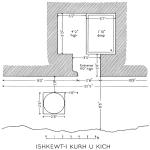

Ishkewt-i Kur u Kich (“Cave of the Boy and Girl”) belongs to a typology of rock-cut tombs conventionally known as “Median,” though these are now generally ascribed to the Achaemenid era. It is one of two such tombs sited in Iraqi Kurdistan, along with the better known example of Ishkewt-i Qyzqapan, 2–3 km to the north; more specifically, it is found in Sulaymaniyah/Slemani province near the village of Shornakh, south of the Sar Sird hills and along the Banzad cliffs (see the plan of the area). The tomb, apparently left unfinished, is carved above a narrow natural terrace of the cliff face, overlooking the Charmaga valley with Mt. Piramagrun in the distance (see the panorama).

Media

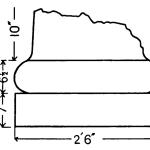

Description & Iconography

“Description & Iconography” general sources: Edmonds 1931, 190–191; von Gall 1966, 25–27 (no. 5); von Gall 1974, 142; von Gall 1988, 580–582; Bahrani 2017, 300–302.

History

The period to which the Kur u Kich tomb should be assigned has aroused considerable discussion. In the decades after its discovery by western scholars in the early 1930s, it was placed into the Median phase of Ernst Herzfeld’s chronology of rock-cut tombs (late 7th–early 6th century BC).1 However, since the 1960s, this scheme has been strongly challenged by Hubertus von Gall, who would rather date this and most other such tombs to the Achaemenid era; according to his view, the tomb would have been built for a local, semi-independent ruler within the territory of the empire.2 It is not clear why it was left unfinished or whether it was ever used.

It is not only the circumstances surrounding the tomb’s creation that are obscure; its ensuing history is entirely unknown. However, it was familiar to the local Kurds by the time of Cecil J. Edmonds’ first visit to the site in the 1930s. According to Edmonds, its name (Kurdish for “Boy and Girl”) derives from the legend that the tomb was created for a young prince who loved a princess beyond the stream of the Tabin.3 She had built him a bridge to facilitate his visits, but the romance ended in tragedy when the bridge collapsed and the youth was drowned.

Early Publications

The cave was known to the local Kurds before it was documented by Western explorers (see “History”). In 1931, Ahmad Beg-i Taufiq Beg, the mutasarrif of Sulaymaniyah, alerted Cecil J. Edmonds—at this time the Director of Antiquities in Iraq—to both Qyzqapan and Kur u Kich; Edmonds published his study of both tombs, including diagrams and photographs, in 1934.1

- 1. Edmonds 1934; cf. Edmonds 1957, 211–212.

Selected Bibliography

Bahrani, Zainab. 2017. Art of Mesopotamia. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Edmonds, Cecil J. 1934. “A Tomb in Kurdistan.” Iraq 1: 183–192.

Edmonds, Cecil J. 1957. Kurds, Turks, and Arabs: Politics, Travel and Research in North-Eastern Iraq. London: Oxford University Press.

Herzfeld, Ernst. 1941. Iran in the Ancient East. London: Oxford University Press.

Mahdi, A. 1950. “Archaeological Sites in the Surdash Region of Sulaimaniyah Province.” Sumer 6: 231–243 [in Arabic].

Von Gall, Hubertus. 1966. “Zu den ‘medischen’ Felsgräbern in Nordwestiran und Iraqi Kurdistan.” Archäologischer Anzeiger, 19–43.

Von Gall, Hubertus. 1974. “Neue Beobachtungen zu den sog. medischen Felsgräbern.” Proceedings of the IInd Annual Symposium on Archaeological Research in Iran, edited by Firouz Bagherzadeh, 139–154. Tehran: Iranian Centre for Archaeological Research.

Von Gall, Hubertus. 1988. “Das Felsgrab von Qizqapan: Ein Denkmal aus dem Umfeld der achämenidischen Königsstrasse.” Baghdader Mitteilungen 19: 557–582.