Site Profile

The rock reliefs at Maltai are located about 70 km north of Mosul in what is today Iraqi Kurdistan. The reliefs were sculpted into cliffs of the Jebel Zawiya on the southern bank of the Duhok River, some 200 m above the river valley now occupied by the city of Duhok (see the panorama). They are named after a small town, west of the historical center of Duhok, that has since been absorbed into the sprawl of the modern city. The reliefs are barely visible from the valley. They comprise four panels repeating the same composition: symmetrical figures of the king flanking a series of divinities mounted on their associated creatures.

The reliefs may be associated with the northern canal system built by the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 704–681 BC) to carry water to his capital city Nineveh. Unlike the reliefs at Khinnis, no inscriptions were found associated with the Maltai reliefs. However, scholars have dated them by style to Sennacherib’s reign, most likely in the period after the capture of Babylon in 689 BC.

Media

Description & Iconography

For general sources on the reliefs, including their condition, measurements, and iconography: Thureau-Dangin 1924; Bachmann 1927, 23–27; Shukri 1954, 86ff; Boehmer 1975; Börker-Klähn 1982, 210–211, nos. 207–210; Reade 1990; Bahrani 2017, 266–267.

History

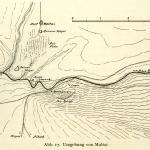

In antiquity, the reliefs were located in a relatively remote area on the fringe of Assyrian territory, though there are two small tells, occupied during the Assyrian era, in the vicinity of the former village of Maltai (see the topographical drawing).1 One of these is in the valley right below the reliefs. Although there are no inscriptions associated with the reliefs, their location and resemblance to the reliefs at Faida and Khinnis suggest that they should be dated to the reign of the same king, who is named as Sennacherib at Khinnis. The reliefs can be dated more specifically to the 680s due to the mushhusshu dragon upon which Assur stands—as this is the symbol of Marduk and Babylon, the choice to include it indicates that the city was conquered by the time the relief was carved (689 BC). Probably, they are to be associated with Sennacherib’s water supply system for his capital city. Topographical study has revealed a large earthwork and canal in the vicinity, running from Maltai towards Girepan in the south, which may have been used to divert waters from the Rubar Dohuk towards the Rubar Faida and eventually on to Nineveh via the Tigris.2

The reliefs marked Assyrian presence and power, indicating the king’s transformation of the landscape as he provisioned water for Assyria. But they were placed high over the valley, set into the face of the steeply rising mountain, and difficult to reach; their images are hardly visible from the valley and therefore their iconographic details cannot be taken entirely in terms of political propaganda.3 The reliefs made the divine sanction of Sennacherib’s hydraulic achievements, as well as his possession of the natural landscape, visually manifest and enduring. The replication of images in a close succession, also seen at Faida, must be understood in the context of the Mesopotamian artistic tradition, and the history of Assyrian sculptural practices, in which repetition and replication were highly significant and meaningful.4

In Late Antiquity (probably in the 5th or 6th century AD), several arcosolia tombs were dug into the rock panels, damaging some of the figures.5 An incomplete tomb, taking the form of an arched niche, destroyed the upper part of several figures in relief 1. Another tomb, this one with a rectangular entrance, was carved into relief 3, destroying parts of its figures. This tomb was actually hollowed out, and its entrance was cut away further by antiquities dealers sometime between 1924 and 1932 (photographs taken before 1924 show the original shape of the tomb entrance).6 It may be wondered if the tombs were placed here only for practical reasons—i.e., because the surface was already flattened—or if there was some significance in their insertion into a monument that was already very ancient.

- 1. Excavated by Victor Place (see Place 1867–1870 (3)).

- 2. Ur 2005, 327–328; 334. However, see also the alternative view that the reliefs were carved under Sargon for his local waterworks program: Morandi Bonacassi 2012–2013, 195–196, and id. 2018, 93–97. Here, the author suggests that the Maltai and Faida canals cannot be identified with those named in Sennacherib’s inscriptions and that they did not connect to the Northern System, but rather that they watered the local settlements; he advances further arguments that the style and iconographic details of the reliefs—and correspondingly the canals—indicate a date during the reign of Sargon.

- 3. Bahrani 2017, 264; see also Malko 2014.

- 4. For the efficacy and significance of repetition in ancient Near Eastern sculpture, see Zainab Bahrani, The Infinite Image (London: Reaktion Books, 2014), 115-144.

- 5. Boehmer 1976.

- 6. Böhl and Weidner 1939–1941.

Early Publications

The earliest published mention of the reliefs at Maltai is found in a letter written in 1845 by Simon Rouet, a diplomat working for the French government in Baghdad; here, Rouet notes that during one of his trips, a Chaldean peasant guided him to a place with impressive rock reliefs.1 Following this report, the reliefs were mentioned by a number of travelers and archaeologists passing through the area, including Austen Henry Layard.2 The carvings were photographed in 1898 by Carl F. Lehmann-Haupt and in 1909 by Gertrude Bell.3 Walter Bachmann took further photographs and made a more systematic study in 1914 based on his visits to Maltai, Khinnis, and Gunduk; however, due to the Great War, Bachmann’s study was not published until 1927.4 In the meantime, an analysis of the reliefs, with new photographs, was published by François Thureau-Dangin in 1924.5 The earliest publication in Arabic was provided by Akram Shukri in 1954.6

- 1. Rouet 1846. See the discussion in Thureau-Dangin 1924, 185.

- 2. Layard (1849 (1), 229–231) provides comments on the reliefs’ imagery and condition; Victor Place, who excavated nearby Tell Maltai in the mid-19th century, makes only brief note of the reliefs and provides an early illustration (1867–1870 (3), pl. 45).

- 3. Lehmann-Haupt 1907, 57–59 and figs. 33–34; for Gertrude Bell’s photos, see “Album M” (nos. 53–57) on the Gertrude Bell Archive online: http://www.gerty.ncl.ac.uk/photos.php. See also images taken in 1922 (Album I; “Dohuk Ridge”).

- 4. Bachmann 1927.

- 5. Thureau-Dangin 1924.

- 6. Shukri 1954, 86ff. and plates 2–4.

See the full list of early publications in Börker-Klähn 1982, 210.

Selected Bibliography

Bachmann, Walter. 1927. Felsreliefs in Assyria, Bawian, Maltai und Gundűk. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 52. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

Bahrani, Zainab. 2017. Art of Mesopotamia. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Boehmer, Rainer M. 1975. “Die neuassyrischen Felsreliefs von Maltai (Nord-Irak).” Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 90: 42–84.

Boehmer, Rainer M. 1976. “Arcosolgräber im Nord-Irak.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 91: 416–421.

Böhl, Franz M. Th. and Ernst F. Weidner. 1939-1941. “Die Lücke in der Reliefgruppe III von Maltai: Zwei Götterbilder von Antikenräubern herausgebrochen.” Archiv für Orientforschung 13: 128–134.

Börker-Klähn, Jutta. 1982. Altvorderasiatische Bildstelen und vergleichbare Felsreliefs. Baghdader Forschungen 4. Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern.

Layard, Austen Henry. 1849. Nineveh and Its Remains. 2 vols. London: J. Murray.

Lehmann-Haupt, Carl F. 1907. Materialien zur älteren Geschichte Armeniens und Mesopotamiens. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung.

Malko, Helen. 2014. “Assyrian Rock Reliefs: Ideology and Landscapes of an Empire.” Assyria to Iberia Exhibition Blog, Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2014/assyria-to-iberia/b…

Morandi Bonacassi, Daniele. 2012–2013. “Il paesaggio archeologico nel centro dell’impero assiro: Insediamento e uso del territorio nella ‘Terra di Ninive.’” Atti dell’Instituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, Classe di scienze morali, lettere ed arti 171: 181–223.

Morandi Bonacassi, Daniele. 2018. “Water for Nineveh: The Nineveh Irrigation System in the Regional Context of the ‘Assyrian Triangle’; A First Geological Assessment.” In Water for Assyria, edited by Hartmut Kühne, 77–116. Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz.

Place, Victor. 1867–1870. Ninive et l’Assyrie. 3 vols. Paris: Imprimierie impériale.

Reade, Julian E. 1990. “Maltai.” In Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie, vol. 7: 320–323. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

Rouet, Simon. 1846. “Lettres de M. Rouet, sur ses découvertes d’antiquites assyriennes.” Journal Asiatique 7: 280–290.

Shukri, Akram. 1954. “Rock Sculptures in the Mountains of North Iraq.” Sumer 10: 86–93 (in Arabic).

Thureau-Dangin, F. 1924. “Les sculptures rupestres de Maltaï.” Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 21: 185–197.