Site Profile

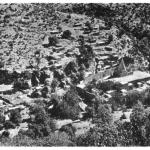

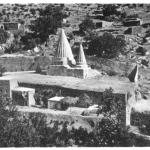

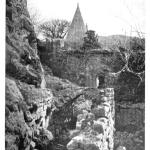

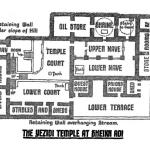

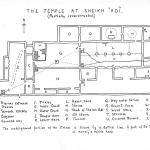

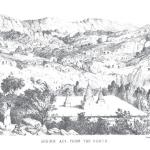

The sanctuary of Shaykh ‘Adī is the central shrine of the sacred valley of Lalish, located about 35 km north of Mosul in the region of Sheykhan, northern Iraq. It is dedicated to Shaykh ‘Adī (d. 1162 AD), the holy man who established the main rules of Yezidism and who preached in the area. Its prominent conical domes can be seen throughout the valley (see the view from the nearby mausoleum of Shaykh Shams, just uphill to the southwest). The sanctuary, sited around Shaykh ‘Adī’s tomb, was begun shortly after his death in the 12th century and was continually expanded as it developed into a center of pilgrimage.

Media

Description & Iconography

“Description & Iconography” general sources: see esp. the recent accounts of Birgul Açikyildiz (Açikyildiz 2009; 2010, 131–146). See also Layard 1849 (1): 282–284; Berezin 1951 [1854]; Badger 1852, 105–110; Bachmann 1913, 9–15; Bell 1924, 275–280; Empson 1928, 119–133; Drower 1941, 194–202; Kreyenbroek 1995, 80–83.

Inscriptions

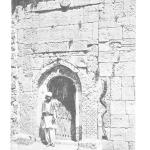

Inscription 1 (Right):

“.تحسين بك بن سعيد بك ، أمير آلشيخان متولي ، ألشيخ عادي '

“Tahsīn Beg bin Saīd Beg, Emīr al-Sheykhan, the vice-regent of Shaykh ‘Adī.”

Inscription 2 (Left):

“ .عمرت باب ألشيخ عادي ، ميان خاتون بنت عبدي بك، على نفقتها ألخاصة'

“The door of Shaykh ‘Adī was built by Mayan Khatun, daughter of Abdī Beg with her own money.”

Inscription 3 (Right):

“.عندما بُنيا باب آلشيخ عادي ، فقير شمو بن مير يادكان مطبخجي و أولاده حجي فارس وموارد و مير حسن'

“The door of Shaykh ‘Adī was built by Feqīr Shemo bin Mīr Yadkan, the Matbakhchī and his children, Hecī Faris, Murad and Mīr Hasan.”

Inscription 4 (Left):

“بابا جاويش ﭘير كمال ، بير ميركان سنجاري ، خادم شيخ عادي، مع تعمير هذا ألباب آلشريف في سنة ١٩٧٩'

“Baba Chawush, Pîr Kemal, Pîr Mīrkan Sinjarī, rendered service to Shaykh ‘Adī by restoration of this holy door in the year of 1979.'

The inscription on the western face of the main entrance reads:

“ بديع بك '

“Badī Beg.”

Inscription 5:

“ .بسم ألله ، عمر هذا ألباب ألشريف..... مشهورآ محل …... جعل آلله آيامه سعيدة'

“In the name of God, this door was built…. Famous…. May god make happy his days.”

Inscription 6:

'بسم آلله آلرحمن آلرحيم ، خالق آلسموات و آلارض ، آحفظ هذا آلمنزل ، محل آلشيخ عادي ألموقر ، شيخ ألمقام ألآول 596 '

“In the name of God, the Merciful and Compassionate, Creator of the heaven and earth, protect this house, the place of the venerable Shaykh ‘Adī, the Shaykh (whose position is elevated) 596/1199.'

Inscription 7 (Center): “This is the date of Ras, the son of Sheikh Emir, and he….Sheikh Gadi from amongst the zealous servants….and he came about out to the Saint of God. God has witnessed about him with a dream of power and near the door stands, permitted, 1230 [AD 1816].”

Left: “The cradle of Sheikh Ismail Gadi.”

Right: “O thou moving rapidly in expectation of God’s will toward Lord Sheikh‘Adī! Hussain Beg, son of Javar Beg, 1231 [1816].”1

Inscription 8:

“The date of the Kavatir Mutadjikh (?) of Sheikh‘Adī in the days of Hussain Beg, 1231 [1816].” 2

Inscription 9:

First: “Sultan Yezeed, the mercy of God be upon him.”

Second: “Sheikh Adi, the mercy of God be upon him.”

Third: “This is the epitaph of Hajji ibn Ismael. Blessedness is inscribed on her gates. Therefore enter them in peace. Amen. In the year 1195.”3

Inscription 10:

Mr. Ṣaliḥ Chete from Turkey (Resha Tribe) renewed the furnishing of Shaykh ‘Adī on 20/4/2007.

Inscription 11 (Proclamation):

I Tahsīn Saīd Ali, Prince of the Yezidis in Iraq and the world, decided to donate all my fortune to the Yezidis Bounties Fund starting from 2/Aug./2012 the beginning of the bounties fiscal year, under the supervision of a committee that oversees this fortune to serve the Yezidis and the Yezidi religion. I will continue holding my authority and power as the prince of the Yezidis and the president of the Yezidi Spiritual Council. And from God reconciliation.

(The Prince)

Tahsīn Saīd Ali

'Inscriptions' sources: Açikyildiz 2009, 301–333; Badger 1852; Berezin 1951.

History

Sketches of Shaykh ‘Adī’s biography are provided by several Arabic-language scholars, including Ibn al-Athir (late 12th/early 13th century) and Muhammed Amin al-Umari (18th century).1 Born in the area of Baalbek, likely in the early 12th century, he is said to have moved to Mosul and then to Lalish along with many followers. Local tradition holds, and many scholars have argued, that the site where he preached—and which later grew into the present sanctuary—was once a church or a mosque/zawiya.2 However, due to the absence of archaeological excavations and the lack of direct evidence for a preexisting structure, it may only be concluded that the sanctuary’s irregular plan is the result of a long process of development from a smaller core—becoming in time an important pilgrimage site for Shaykh ‘Adī’s followers.3

Following Shaykh ‘Adī’s death (in 1162, according to al-Umari), the importance of his tomb grew. As to when it became a center of pilgrimage, the evidence is vague. The geographer and historian Yakut al-Hamawi—writing in the early 13th century AD—mentions Lalish as a district of Mosul and the place where Shaykh ‘Adī lived, without noting the presence of his tomb.4 Although he does not make note of a sanctuary, Ibn al-Fuwati describes how, during a local rebellion, the ruler Badr ad-Din Lu’Lu’ (r. 1225–1259) ordered Shaykh ‘Adī’s bones to be exhumed and burned, which may suggest a site of religious pilgrimage by this date.5 In any case, the building was constructed in many phases over centuries; the most recent addition, the sector to the south of the assembly hall serving practical needs, was built around 1989.6 It has also faced destructive events, including the aforementioned campaigns of Badr ad-Din Lu’lu’, and later those of a local leader who declared holy war against the Yezidis (15th century).7 In 1892, the Ottomans launched a campaign against the Yezidis, in which the complex was partially sacked and the architectural fabric sustained significant damage.8 In all cases, the sanctuary was rebuilt, often by relaying the fallen stones. Although Lalish was largely spared from the tragic and destructive attacks of ISIS/Daesh in 2014, a major restoration of the sanctuary of Shaykh ‘Adī is underway (as of 2021).

- 1. For the primary sources on the history of Shayk Adi’s life, see Siouffi 1885; Nau and Tfinkdji 1915–1917. See also Empson 1928, 103–111.

- 2. On the issue of a preexisting church/mosque, see esp. Fiey 1965, 796–815; Bois 1967, 88–99. See also the overview in Açikyildiz 2009, 323–325.

- 3. Açikyildiz 2009, 325; Açikyildiz 2010, 143.

- 4. Yakut, Mu’jam al-Buldan, vol. 4; see Nau and Tfinkdji 1915–1917, 150.

- 5. Ibn al-Fuwati, al-Hawadith al-jami’a; see Açikyildiz 2010, 144.

- 6. Açikyildiz 2010, 144.

- 7. Açikyildiz 2010, 45.

- 8. See Empson 1928, 128. The site was ordered to be converted into an Islamic madrassa, but the Yezidis retook it in 1904, beginning restoration.

Early Publications

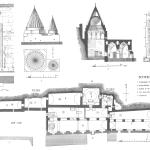

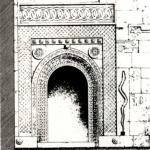

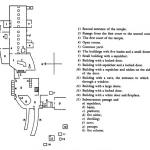

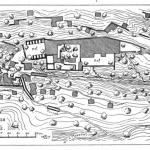

Several Arabic-language authors, such as Yakut al-Hamawi, provide some background information on Shayk Adi’s time in Lalish before the sanctuary was built.1 Much later, during the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, many of the European travelers visiting the Yezidis left descriptions of the sanctuary.2 Some of these visitors diagrammed the ground plan and elevation of the building (see, e.g., the plan by R. H. W. Empson; see the plan and section by Walter Bachmann).3 Others made drawings of particular features (see Walter Bachmann’s 1911 drawing of the Derîyê Kapî). Several travelers of the early 20th century, including Gertrude Bell, also took photographs of the site.4 Visitors interested in documenting various aspects of the sanctuary and its rituals continued to arrive throughout the first half of the 20th century, including Freya Stark and Ethel Drower of England,5 and Sadid al-Damlooji and ʻAbd al-Razzāq Hasani of Iraq.6

- 1. See the sources in Siouffi 1885; Nau and Tfinkdji 1915–1917, 149–154.

- 2. E.g. Ainsworth 1842 (2), 183-185; Berezin 1951 [1854], 68–73; Layard 1849, 282–284; Badger 1852 (1), 105–110; Bachmann 1913, 9–15; Bell 1924: 275–279; Empson 1928 (1), 12–16. For a fuller list of these visitors, see Açikyildiz 2009, nn. 6–7.

- 3. Empson 1928, pl. between pp. 124–125 (cf. the diagrams in Berezin 1951 [1843] and Badger 1852.; Bachmann 1913, pl. 15).

- 4. Gertrude Bell Archive, Album M, nos. 45–49; see also Bachmann 1913, pl. 14.

- 5. Stark 2011 [1937], 108–114; Drower 1941, 159–162.

- 6. Al-Damoojli 1949, 205; Hasani 1951, 25.

Selected Bibliography

Açikyildiz, Birgül. 2009. “The Sanctuary of Shaykh Adī at Lalish: Centre of Pilgrimage of the Yezidis.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 72: 301–333.

Açikyildiz, Birgül. 2010. The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture, and Religion. London: Tauris.

Al-Damlooji, Sadiq. 1949. Al-yazīdīya [The Yezidis]. Mosul: Matba’t al-ittihad (in Arabic).

Bachmann, Walter. 1913. Kirchen und Moscheen in Armenien und Kurdistan. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

Badger, George Percy. 1852. The Nestorians and Their Rituals: With the Narrative of a Mission of Mesopotamia and Coordistan in 1842–1844 [ ... ]. London: J. Masters.

Bell, Gertrude. 1911. Amurath to Amurath. London: Dutton.

Berezin, Ilya. 1951 [1854]. “A Visit to the Yezidis in 1843.” In The Northern Jazira, ed. Henry Field, 67–79. Part 2, no. 1 of The Anthropology of Iraq. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology.

Bois, Thomas. 1967. “Monastères chrétiens et temples yézidis dans le Kurdistan irakien.” Al-Machriq 61 (1): 88–101.

Drower, Ethel S. 1941. Peacock Angel. London: J. Murray.

Empson, R. H. W. 1928. The Cult of the Peacock Angel: A Short Account of the Yezidi Tribes of Kurdistan. London: H. F. & G. Witherby.

Fiey, Jean M. 1965. Assyrie chrétienne: Contribution à l’étude de l’histoire et de la géographie ecclésiastiques et monastiques du nord de l’Iraq. Vol. 1. Beyrouth: Librairie Orientale.

Hasani, ʻAbd al-Razzāq. 1951. Al-Yazīdīyūn fī ḥāḍirihim wa-māḍihim. Ṣaydā: Maṭbaʻat al-ʻIrfān (in Arabic).

Kreyenbroek, Philip G. Yezidism: Its Background, Observances, and Textual Tradition. Lewiston, NY: E. Mellen Press, 1995.

Layard, Austen Henry. 1849. Nineveh and Its Remains. 2 vols. London: J. Murray.

Nau, François, and Joseph Tfinkdji. 1915–1917. “Recueil de textes et de documents sur les Yézidis.” Revue de l’Orient Chrétien 20: 142–200, 225–275.

Siouffi, N. M. 1885. “Notice sur le Shaykh Adi et sur la secte des Yézidis.” Journal Asiatique 8/5: 78–98.

Stark, Freya. 2011 [1937]. Baghdad Sketches: Journeys through Iraq. London: Tauris Parke.

Wigram, W. A., and Edgar T. A. Wigram. The Cradle of Mankind: Life in Eastern Kurdistan. London: A. and C. Black, 1914.