Site Profile

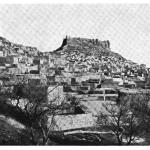

The city of Mardin, capital of the eponymous province of modern Turkey, is strategically sited near a key pass through the east-west chain of mountains (Mardin Dağlari) that includes the Tur Abdin. This pass links Diyarbakır (ancient Amida), to the north, with Nusaybin (ancient Nisibis) to the south; the city is also a crossroads of other important routes. It is laid out across a high hill, dominated by a craggy upper citadel that rises to almost 1200 m above sea level. This elevated position endows the city with spectacular views over the upper Mesopotamian plain to the south. Mardin has been continually occupied from antiquity until the present day. Its surviving historical monuments range in date from the medieval era to the late Ottoman period.

Media

Description & Iconography

General sources on Mardin’s general layout and architecture: Gabriel 1940, 1–44; Sinclair 1989, 201–203; Altun 1972; Hollerweger 1999, 314–325; Alioğlu 2000; Açıkyıldız-Şengül 2018.

History

Although its strategic position suggests that it could have been occupied far back into antiquity, there is no archaeological evidence for a pre-classical settlement on the later site of Mardin; a Neo-Assyrian legal document does refer to a place called Mardiānê, which may indicate that it was occupied by this time.1 The earliest certain known reference to the city comes only in Late Antiquity—in the Res Gestae of the Roman historian Ammienus Marcellinus (4th cent. AD), who describes Maride as a limes; it remained a frontier settlement into the Early Byzantine era.2 In 640, it was brought into the early Islamic empire along with the broader region of Upper Mesopotamia (encompassing, e.g., nearby Dara).

Mardin’s importance increased under the succession of dynasties that followed this conquest. In the 870s, Abbasid control was contested by the Hamdanid dynasty based at Mosul. It was under their auspices that Mardin’s citadel fortress was substantially rebuilt. After their defeat by the Buyids in 990, the city fell to the Marwanids based at Diyarbakır; late in the following century, their domain was taken under the direct control of the Seljuks. The geographers and historians of this period of Mardin’s history offer few details on the city, though they note its strength and splendor and clearly considered it very important.3 While its ruling dynasties were Muslim, the city maintained a large population of Christians. By the 8th century, it was the center of a bishopric based at the nearby monastery of Deyrul Zafaran.

Mardin flourished under the Artuqid dynasty, who ruled as emirs under the nominal suzerainty of the Seljuks and later, the Ayyubids. The family solidified its hold on the city in 1108, when it was established as a seat of power under Il-Ghazi bin Artuq. His line ruled in Mardin until 1408, though the Artuqid emirate was a complex political entity that involved several dynastic branches and capital cities (including one at Hasankeyf). During this period, a number of important monuments were constructed in the city under Artuqid patronage: at least one hammam, several madrassas, and a number of mosques, including the Ulu Cami. The churches built durin this period attest to the continuing flourishing of Mardin’s Christian population; it may also be noted that the Jacobite patriarchate was moved to Mardin in 1171.4 By this time, if not earlier, the city was also home to a small Jewish community.5

In 1260, a Mongul army besieged Mardin; they failed to take it but caused considerable turmoil, and the Artuqids agreed to a kind of vassalage for a time. Timur managed to capture the city in 1401, during the reign of Malik ‘Isa, but he still could not secure the upper citadel. Timur’s siege triggered a complex series of events that led to Malik ‘Isa’s cession of the city in 1408 to the Qara Qoyunlu dynasty (quickly to be superseded by the rival Aq Qoyunlu in 1432). In 1507, Mardin, along with much of eastern Anatolia, was annexed into the Persian domain under Shah Ismail, founder of the Safavid dynasty.

Only a decade later, Safavid power had collapsed in the area, and the region of Mardin came under the sway of the Ottoman Empire. It was initially incorporated into the eyalet of Diyarbakır, serving as the center of one of its sanjaks; by the 1700s, however, it was a dependency of the Baghdad pashas. Until the later 19th century, there were few major monuments built in Mardin under the Ottomans. This changed with the period of the Tanzimat reforms, initiated in the 1830s. Although this triggered Mardin to revolt for several decades, the city was returned to the Diyarbakır vilayet by 1870; at the same time, the local government embarked on a concerted building campaign, designing a new administrative center along Hükümet Caddesi in the city’s northeast. As the first buildings in Mardin to be constructed in an Ottoman imperial (rather than traditional local) style, it has been argued that they reflect the reform era’s interest in centralized authority and administration.6 A number of other, non-imperial constructions, including wealthy townhouses, testify to the prosperity of the city at this time. Travelers visiting Mardin during the late 19th and early 20th centuries report that of the city’s population of approximately 50,000, its Muslim and Christian residents were almost equal in number; several Jewish families, up to 50, were also counted at this time.7

The era of the First World War and its aftermath was a turning point for Mardin, as for the entire region. With the establishment of the modern Turkish state in the early 1920s, Mardin became the capital city of its own province; the population has grown during the modern period, and is now estimated at over 80,000. Though most of the Jewish and Christian residents left during the course of the 20th century, a Christian community still lives here. To this day, Arabic is the primary spoken language throughout the city, with many speaking Turkish and/or Kurdish as well.

- 1. On the possible connection between Mardiānê and Mardin, see Radner 2006, 291.

- 2. Amm. Marc. 19.9.4. Note that he pairs this with a nearby fortress called Lorne. The same pairing recurs in Procopius (Buildings 2.4.14), who claims these among the string of fortresses restored by Justinian.

- 3. See the summary comments in Minorsky 1991, 540.

- 4. These include the Church of the Forty Martyrs and the Church of Mor Shmuni; see Hollerweger 1999, 314–325.

- 5. It is unclear exactly how far back there was a Jewish community in the city, but it was certainly established by the 13th century. For a brief overview, see Ben-Yaacob 2007.

- 6. See Açıkyıldız-Şengül 2018, 163–164.

- 7. Warkworth 1898, 227; Tfinkdji 1914. On the population of the Jewish community, see Ben-Yacoob 2007.

“History” general sources: Gabriel 1940, 6–7; Minorsky 1991.

Early Publications

During the Medieval era, Mardin was discussed by several geographers and historians writing in Arabic, including Yakut al-Rumi al-Hamawi.1 In the early modern period, the city became a frequent stopping point for visitors to the area from far and wide.2 In the mid-1600s, it was on the itineraries of two famous voyagers: Evliya Çelebi, from the Ottoman court at Istanbul, and Jean-Baptiste Tavernier from France.3 With the wave of Western travelers passing through the region from the early 19th century—often primarily though not exclusively interested in visiting the region’s Christian communities—Mardin remained a destination of interest.4 Some of these visitors are brief in their comments, distilled to the standard awe at the city’s elevated position (for instance, William Ainsworth: “The prospect of Mardin, which may truly be called the Quito of Mesopotamia, is one of the most striking that can well be conceived…”).5 Others, including James S. Buckingham and Horatio Southgate, provide more detailed descriptions.6 During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, some travelers began to include photographic images of the city in their publications (see Lord Warkworth’s view of the Ulu Cami minaret and plain below Mardin; see Conrad Preusser’s view upon the city and citadel.7

- 1. See esp. Yakut al-Rumi al-Hamawi, Mu’jam al-Buldan (IV), 390; further in Minorsky 1991, 540.

- 2. See the listing in Minorsky 1991, 542.

- 3. Çelebi, Seyahâtnâme (IV), 59; Tavernier 1676, 169.

- 4. Ainsworth 1942 (2), 114–115.

- 5. Ainsworth 1942 (2), 114-115.

- 6. Buckingham 1827, 177–194 (esp. 188–194; note also the somewhat fanciful drawing of the city, p. 177); Southgate 1840, 273–287 (focusing on the Christian communities, though discussing other aspects of the city as well).

- 7. Preusser 1911, 53–54.

Selected Bibliography

Açıkyıldız-Şengül, Birgül. 2018a. “Architects, Stonemasons, and Building Artisans of Mardin: Builders and Maintainers of a Local Tradition.” In Prof. Dr. Zülküf Güneli’ye Armağan – Tasarım & Koruma, edited by E. E. Dağtekin, F. M. Halifeoğlu, G. Payaslı Oğuz, and H. Özyılmaz, 61–70. Istanbul: Birsen Yayınevi.

Açıkyıldız-Şengül, Birgül. 2018b. “Mardin in the Post-Tanzimat Era: Heritage, Changes and Formation of an Urban Landscape.” Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies 5 (2): 159–185.

Alioğlu, E. Füsan. 2000. Mardin: Şehir dokusu ve evler [Mardin: City Fabric and Houses]. Istanbul: Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı (in Turkish).

Altun, Ara. 1971. Mardin’de Türk devri mimarisi [Architecture of the Turkish Era in Mardin]. Istanbul: Yazan (in Turkish; English summary, pp. 152–156).

Ben-Yaacob, Abraham. 2007. “Mardin.” Encyclopaedia Judaica, edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed., vol. 13, 518. Detroit: Macmillan Reference.

Buckingham, James S. 1827. Travels in Mesopotamia […]. London: H. Colburn.

Gabriel, Albert. 1940. Voyages archéologiques dans la Turquie orientale. Paris: E. de Boccard.

Hollerweger, Hans, et. al. 1999. Turabdin: Living Cultural Heritage. Linz: Freunde des Tur Abdin.

Minorsky, V. 1991 “Mardin” (updated by C. E. Bosworth). Encyclopedia of Islam. New ed., vol. 6: 539–542.

Preusser, Conrad. 1911. Nordmesopotamische Baudenkmäler altchristlicher und islamischer Zeit. Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 17. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs.

Radner, Karen. 2006. “How to Reach the Upper Tigris: The Route through the Tūr ‘Abdīn.” State Archives of Assyria Bulletin 25: 273–305.

Sinclair, T. A. 1989. Eastern Turkey: An Architectural and Archaeological Survey. Vol 3. London: Pindar.

Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste. 1676. Les six voyages de Jean Baptiste Tavernier, ecuyer baron d’Aubonne, en Turquie, en Perse, et aux Indes […]. Vol. 1. Paris: G. Clouzier and C. Barbin.

Tfinkdji, J. 1914. “L’église chaldéenne catholique autrefois et aujourd’hui.” Annuaire Pontifical Catholique 17: 449–525.

Warkworth, Lord [Henry Algernon George Percy]. 1898. Notes from a Diary in Asiatic Turkey. London: Arnold.