Site Profile

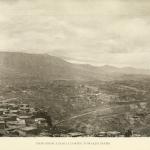

Amadiya/Amedi is located in the Duhok Governorate of Iraqi Kudistan, about 25 km south of the Turkish border. It is situated within the basin of the Sapna River (a tributary to the Great Zab), in a hilly valley surrounded by two parallel ranges of the Zagros Mountains to the north and south. An ideal citadel, the city of was built upon a precipitous rock outcrop soaring 1985 m above sea level and visible in the landscape from a great distance. The earliest surviving writings on the town focus on its refoundation during the period of the Zengid Dynasty in the 11th–12th centuries AD, though it is clear that occupation stretches back far before this, even into antiquity. This is evinced most conspicuously by an ancient staircase and three reliefs dating to the Parthian era along the approach to the citadel’s western gate. A number of further monuments found within and around the citadel attest to the city’s rich and varied history.

Media

Description & Iconography

History

Given Amadiya/Amedi’s strategic and naturally fortified position commanding the surrounding valleys, it seems likely that it was occupied from a very early time, a fact that is mentioned by Yaqut al-Rumi al-Hamawi. However, no area in the citadel has been systematically excavated, and there are no known textual sources that provide information on the site in antiquity. We are left with only hints around its earliest history. An early medieval name for the citadel, Āshib, is related to the root for the Akkadian term for “dwelling” or “settlement,” which may suggest an occupation phase predating the Parthian-era rock reliefs and staircase.1 These reliefs—the citadel’s most readily datable archaeological features—can be assigned to the 1st century BC–2nd century AD on the basis of style. At this time, the area of what is now northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey was divided amongst several semi-independent kingdoms. The general area of Amadiya/Amedi seems to have been near the shifting border between Gordyene (which later became a vassal to Rome) and Adiabene (in the Parthian sphere of influence); by the 1st century BC, it seems clear that it was within the Adiabenean dominion.2 The site remained occupied into Late Antiquity, during which time Adiabene was a border province of the Sasanian Empire; the Christian community must have been established by this time, as attested by the arcosolia graves dug into the cistern (5th/6th century AD).3

The early medieval phase of Amadiya/Amedi is also obscure. Later medieval scholars writing in Arabic refer to it as a long-occupied site, but they do not go into any significant detail. By the 11th century, the region was settled predominantly by a Kurdish tribe called the Hakkari, one of whose fortresses was apparently located on the citadel in question. Both Yakut al-Rumi al-Hamawi and Ibn al-Athir (referring to the citadel as Āshib) recount its capture by the Seljuk emir and founder of the Zengid dynasty, Imad al-Din Zengi (r. 1085–1146 AD); they assert that upon its ruins a new fortress was built, named al-‘Imadiyya in the conqueror’s honor.4 The Zengid period lasted in Amadiya/Amedi until the early 13th century. During this time, the city was home to a diverse population that included people of the Muslim, Christian, and Jewish faiths. It was this religious diversity that attracted one of the earliest voyagers to the city: in 1170, Benjamin of Tudela (Spain) visited during the course of his travels, counting 2000 members of the Jewish community—one of the largest in the entire region, speaking Aramaic (also the language of the Christian community).5 Shortly after this time, the Ezekiel synagogue was built.

In 1225, Badr al-Din Lu’lu’—atabeg and regent of the Zengid heir—brought Mosul, Amadiya/Amedi, and several other cities in the region under is personal control.6 This ruler, of Hakkari Kurdish affiliation, traced his descent from the figure of Baha ad-Din, who was himself supposed to be related to the Abbasids. Lu’lu’s lineage ruled what became known as the Bahdinan Emirate under the nominal suzerainty of the Abbasids, with Amadiya/Amedi serving as its seat of power. Along with the other Kurdish principalities in the vicinity, it maintained a complex relationship with the evolving empires that surrounded it—particularly, from the early 16th century, that of the Ottomans. However, it was one of the most prosperous and independent of the regional emirates during the 17th and 18th centuries. At its height, it encompassed a swath of territory that included Zakho, Duhok, and Akre. Visitors from the 16th through the early 19th century were invariably impressed by the strength of the dynasty and its capital city (see “Early Publications”). They also describe a multi-ethnic community that remained religiously diverse. The residents spoke Kurdish and Arabic, along with Aramaic among the Jews and Christians.

Significant troubles began in 1830, when Bahdinan participated alongside several other emirates in a revolt against Ottoman domination; in the midst of this crisis, the ruler of the neighboring Soran Emirate seized the opportunity to consolidate his regional power, deposing the Bahdinan prince and taking Amadiya/Amedi under his sway in 1833. The brutal struggle devasted the local population. A few years later, the Ottomans supported the restoration of the Bahdinans. However, in 1842, the Ottomans themselves overthrew the emirate, besieging Amadiya/Amedi and destroying much of the old urban fabric. No longer a capital city, it was now absorbed into the Ottoman Empire. Travelers of the mid-19th century refer to the city’s impoverishment and ruinous condition resulting from the conflict.7 After the Great War, Amadiya/Amedi—along with the rest of the area—was contested between Turkey and the British Mandate of Iraq; a large number of British troops, as well as a Turkish administrator, were stationed here during this time. The city was officially incorporated into Iraq after the Mosul Settlement of 1926.

In 1958, with the end of the Iraqi monarchy, Amadiya/Amedi became involved in the regional autonomy movement and war that lasted through the 1960s. During this conflict, the city was bombed by the Iraqi air force, resulting in great loss of life and further destruction of the city’s historical buildings.8 Since 1992, Amadiya/Amedi has been administered by the Kurdish Regional Government. Situated within the Duhok Governorate, it serves as the district capital of the same name, about 2700 km2 and home to about 10,000 people. The citadel itself numbers roughly 4000 inhabitants; the city’s Christian population has greatly diminished and the Jewish community has entirely emigrated, though the tomb of Hazana is still greatly venerated by both Muslims and Christians.

- 1. Bahrani et al. 2019, n. 7.

- 2. On the territorial definitions of these two kingdoms, see Michal Marciak, Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene: Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia between East and West (Leiden: Brill, 2017).

- 3. Boehmer 1976.

- 4. Yakut al-Rumi al-Hamawi, Mu’jam al-Buldan (vol. 3, S–F, 717). Ibn al-Athir, al-Kāmil fit-Tārīkh (vol. 9 [From the Year 489 to the Year 561 Hijri], 275, 326); see the English translation in Richardson 2006, 366. Ibn al-Athir suggests this occurred in either 528 H (1133 AD) or 537 H (1142/1143 AD); Yakut gives the date as 537 H (1142 AD). On these primary sources, among others, see Streck and Minorsky 1960.

- 5. For an overview of the city’s Jewish community, see Fischel 2007. This includes a discussion of the messianic movement, led by David Alroy, to capture Amadiya/Amedi in the early 12th century.

- 6. The primary source for the accession of Badr al-Din Lu’lu’ is Ibn al-Athir’s al-Kāmil fit-Tārīkh; for an English translation of the relevant section, see Richards 2012, 185–187. On the succeeding Bahdinan Emirate, see the overview in Hassanpour 1998.

- 7. E.g. Layard 1849 (1), 161; Badger 1852 (1), 199.

- 8. See Amman 2004/2005, 220.

“History” general sources: Streck and Minorsky 1960; Hassanpour 1998; Amman 2004/2005.

Early Publications

Geographers and historians writing in Arabic, including Yakut al-Rumi al-Hamawi, are the key primary sources for the history of Amadiya/Amedi during the medieval period.1 They provide important information on the status of the citadel before the Zengid occupation; for example, Ibn al-Athir writes:

- “In this year [537 H- 1142/1143 AD/CE] Atabeg Zengi sent an army to the citadel of Āshib, which was the greatest of the fortresses of the Hakkari Kurds and the strongest, where they kept their wealth and their families. They besieged it and pressed hard on the defenders, until they took it and then he ordered its destruction and the construction of the citadel known as al-‘Imādiyya to replace it. Among their fortresses this al-‘Imādiyya had been a great one, but they destroyed it on account of its size, because it was very large indeed and they were incapable of holding it. At this present time Āshib was demolished and al-‘Imādiyya was rebuilt. It was called al-‘Imādiyya with reference to his [Imad al-Din Zengi's] title.”2

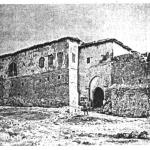

Benjamin of Tudela passed through in 1170, a few decades after the Zengid conquest; he was particularly interested in the city’s considerable Jewish population, recounting in detail the story of David Alroy’s messianic revolt earlier in the same century.3 More detailed observations on the city’s government and customs were offered by Sharafkhan Bitlisi (16th century) and Evliya Çelebi of the Ottoman court at Istanbul (visiting in 1655).4 By Çelebi’s time, Western voyagers were also beginning to pass through the region, the first being the French adventurer Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1663).5 In the 1700s and early 1800s, certain Dominican monks who lived for periods of time in the city recorded brief comments on its monuments.6 With the increasing numbers of travelers arriving in the city from the 19th century on—including, e.g., Austen Henry Layard—several extensive descriptions of the city were published.7 The earliest photographic images of the city were taken during the decades around the turn of the 20th century.8 The site was studied and documented by the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage of Iraq in the mid-20th century, and certain of its monuments were published by Tariq al-Janabi in 1982.9

- 1. See a listing in Streck and Minorsky 1960. It is not clear whether these geographers visited the cities in person or not.

- 2. Ibn al-Athir, al-Kāmil fī al-tārīkh (vol.9, 326); for English translation: Richardson 2006, 366.

- 3. Benjamin of Tudela, Sefer ha-Massa‘ot (ed./trans. Marcus N. Adler, 1907), 54–56.

- 4. On Bitlisi’s Sharafname, see the summary in Ammann 2004/2005, 192. On Çelebi’s Seyahatname (vol. 4), see the summary in van Bruinessen 2000, 9–11.

- 5. Tavernier 1677, 281.

- 6. Including Domenico Lanza and Giuseppe Campanile; see the quotations in Galletti 2001, 116–117.

- 7. John Kinneir described the territory of Amadiya/Amedi without going up the citadel (Kinneir 1818, 456). Visitors exploring the citadel itself include, among others: William Ainsworth, visiting in 1840 (Ainsworth 1842 (2), 195–204); Henry Ross, visiting in the mid-1840s (Ross 1902, 106–112); George Percy Badger, visiting in the later 1840s (Badger 1852 (1), 199–207); Austen Henry Layard, visiting in 1846 (Layard 1849 (1), 157–166).

- 8. Binder 1887, 196–207, with the photographs inserted passim; also note here the author’s interpretive sketch of the city’s bazaar. Warkworth 1898, 182–184, with plate; Sykes 1904, 165–169 (photographs passim); Bachmann, diagrams and photographs inserted in pp. 1–3, pl. 1.

- 9. Al-Janabi (1982) focuses mainly on a door and minbar from Amadiya/Amedi’s Great Mosque (see further in the MMM site entry on this monument) but also discusses the Mosul Gate and publishes a key photograph of it (p. 253 and pl. 175).

Selected Bibliography

Ainsworth, William. 1842. Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea, and Armenia. 2 volumes. London: J. W. Parker.

Al-Hamawi Al-Rumi Al-Baghdadi, Yaqut. 1868. Mu'jam al-Buldan [Jacut's Geographisches Wörterbuch aus den Handschriften]. Edited by Ferdinand Wüstenfeld. Vol. 3. Leipzig: In Commission Bei F. A. Brockhaus.

Al-Janabi, Tariq. 1982. Dirāsāt fī al-ʻimārah al-ʻIrāqīyah fī al-ʻuṣūr al-wusṭá. Baghdad: Wizārat al-Thaqāfah wa-al-Iʻlām. [Turkish translation: Al-Janabi, Tarık. 1982. Studies on Medieval Iraqi Architecture. Baghdad: Iraqi State Antiquities and Cultural Heritage Board.]

Ammann, B. 2004/2005. "Kleine Geschichte der Stadt Amadiya: Von streitbaren Fürsten, kurdischen Juden und grausamen Zeiten." Kurdische Studien 4/5, 175–226.

Bachmann, Walter. 1913. Kirchen und Moscheen in Armenien und Kurdistan. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrich.

Badger, George Percy. 1852. The Nestorians and Their Rituals. 2 volumes. London: J. Masters.

Bahrani, Zainab, Haider Almamori, Helen Malko, Gabriel Rodriguez, and Serdar Yalcin. 2019. "The Parthian Rock Reliefs and Bahdinan Gate in Amadiya/Amedi: A Preliminary Report from the Columbia University Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments Survey." Iraq 81: 47-62.

Binder, Henry. 1887. Au Kurdistan en Mésopotamie et en Perse. Paris: Maison Quantin.

Boehmer, Rainer M. 1976. "Arcosolgräber im Nord-Irak." Archaeologischer Anzeiger 91: 416-421.

Erich Brauer. 1993. The Jews of Kurdistan. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Fischel, Walter J. 2007. "'Amadiya." In Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd edition, vol. 2, dzl. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 27-28. Detroit: Macmillan Reference.

Galletti, Mirella. 2001. "Kurdish Cities through the Eyes of Their European Visitors." Oriente Moderno (n.s.) 20 (81): 109-148.

Hassanpour, A. 1998. "Bahdīnān." In Encyclopaedia Iranica, 3. Volume (5): 485.

Ibn Al-Athir, Ali. 2003. al-Kāmil fī al-tārīkh [The Complete History]. 4th ed. Edited by Mohammed Al-Daqaq. Vol. 9. Beirut: Dar al-kotob Al-Ilmiyah.d

Kinneir, John Macdonald. 1818. Journey through Asia Minor, Armenia, and Coordistan in the Years 1813 and 1814. London: J. Murray.

Layard, Henry Austen. 1849. NINEVEH and Its Remains. 2 volumes. London: J. Murray.

Marf Zamua, Dlshad A. 2008. "Al Manhutat al Sakhriya al Qadima fi Madinat (Amedi) Al Amediyah." Subartu 2008 (2): 113–121 (in Arabic).

Richards, D. S. (dzl.). 2006. The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kāmil fīl-Ta'rīkh, Part 1: The Years 491–541/1097–1146; The coming of the Franks and the Muslim response. Crusade Texts in Translation 13. Aldershot, UK; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Richards, D. S. (dzl.). 2010. The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kāmil fīl-Ta'rīkh, Part 3: The Years 589–629/1193–1231; The Ayyubids after Saladin and the Mongol Menace. Crusade Texts in Translation 17. Aldershot, UK; Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Ross, Henry James. 1902. Letters from the East by Henry James Ross, 1837-1857. London: Dent.

Streck, M., and V. Minorsky. 1960. "'Amādiya.' In Encyclopaedia of Islam, new edition, 1. Volume: 426-427. Leiden: Brill.

Sykes, Mark. 1904. Dar-ul-Islam: A Record of a Journey Through Ten of the Asiatic Provinces of Turkey. London: Bickers.

Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste. 1677. Les six voyages de Jean Baptiste Tavernier, ecuyer baron d'Aubonne, en Turquie, en Perse, et aux Indes [...]. Volume 1. Paris: G. Clouzier and C. Barbin.

Van Bruinessen, Martin. 2000. "Kurdistan in the 16th and 17th Centuries, as Reflected in Evliya Çelebi's Seyahatname." Journal of Kurdish Studies 3: 1-11.

Warkworth, Lord [Henry A. G. Percy]. 1898. Notes from a Diary in Asiatic Turkey. London: Arnold.