Site Profile

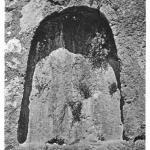

The citadel of Amadiya/Amedi is approached from the west along an ancient pathway that leads toward the Bahdinan Gate, a monumental entrance built in the 13th century AD. Along the final stretch of this long ascent, the visitor passes three ancient reliefs carved directly into the cliff walls (see the photogrammetric reconstruction). The sculptures all represent single human figures and are dated by style and iconography to the Parthian era.

Media

Description & Iconography

The information presented here has been adapted from Bahrani et al. 2019. See also see Mathiesen 1992 (2), 183–194 (nos. 142–143); Marf Zamua 2008, 115–116; Miglus et al. 2018.

History

The iconographic and stylistic features of the Amadiya/Amedi rock reliefs clearly indicate that they were carved during the Parthian period, ca. 1st century BC–2nd century AD.1 At this time, much of northern Mesopotamia was ruled by various vassal kingdoms—such as Hatra, where some of the closest sculptural parallels were created. Although the political status of Amadiya/Amedi during the period in question is unknown, the general area seems to have been controlled by Adiabene (see further in the Amadiya/Amedi site entry).2 However—as with most rock-carved reliefs from this period—the sculptures lack inscriptions that would place them within the reign of a particular ruler. It is also uncertain as to whether they were all carved around the same approximate timespan, or whether they were added at different stages during the centuries of the Parthian era. It may be noted that there are significant variations in their stylistic qualities. Relief 3 features naturalistic modeling and dynamic movement of the body; this may suggest an early date in the Parthian period, when Greek Hellenistic influences were stronger—possibly during the 1st century BC. The female figure of Relief 2 could be of the same early date. The style of Relief 1, with its frontal figure, is more in keeping with the art of the first two centuries AD. Nonetheless, different styles coexisted in Mesopotamia during the entirety of the Parthian era, so it is not impossible that the reliefs were carved around the same time.

Interestingly, the reliefs, along with the contemporaneous staircase, were preserved through Amadiya/Amedi’s centuries of post-antique occupation. Even as the religious spectrum of the city’s population became predominantly Christian, Muslim, and Jewish, the sculptures show no evidence of deliberate effacement or iconoclastic activity. The Zengid-era defensive walls and the Bahdinan Gate, 12th–13th centuries AD, were built without any attempt to remove these highly visible pre-Islamic images; the resulting ensemble enacted a dialogue between the citadel’s past and present.3

Early Publications

Although Amadiya/Amedi was described by geographers and travelers from the medieval period on, the reliefs outside the Bahdinan Gate were not formally documented until the 19th and early 20th centuries (at least according to the preserved sources). William Ainsworth, who only noted the relief closest to the Bahdinan Gate, compared the figure’s dress to images of Shapur I and assigned it to the Sasanian era (1842).1 Ainsworth’s conjecture was relatively close to the mark; some commentators were much vaguer in their speculations, perhaps in part due to the fact that the sculptures were apparently already very worn. When Mark Sykes noticed the relief closest to the Bahdinan Gate, he responded that this “curious figure…may be of the Misty Hittites or later, but [is] so defaced that only the most learned and boldest of antiquaries would dare to give a date” (1904).2 In fact, Austen Henry Layard had already hit upon the date now agreed on by scholars, assigning the same relief to the period of “the Arsacian kings” (1849).3 None of these visitors made any sketches of the sculptures. However, in 1911 Walter Bachmann marked the position of all three niches in his diagram of the staircase and gate. He also took photographs of Relief 1 and Relief 3 (see the historical photographs; he apparently did not recognize that the middle niche held a very worn figure (Relief 2).4

Selected Bibliography

Ainsworth, William. 1842. Travels and Researches in Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Chaldea, and Armenia. 2 vols. London: J. W. Parker.

Bachmann, Walter. 1913. Kirchen und Moscheen in Armenien und Kurdistan. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrich.

Bahrani, Zainab, with Haider Almamori, Helen Malko, Gabriel Rodriguez, and Serdar Yalcin. 2019. “The Parthian Rock Reliefs and Bahdinan Gate in Amadiya/Amedi: A Preliminary Report from the Columbia University Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments Survey.” Iraq 81: 47–62.

Layard, Austen Henry. 1849. Nineveh and Its Remains. 2 vols. London: J. Murray.

Marf Zamua, D. 2008. “Al Manhutat al Sakhriya al Qadima fi Madinat (Amedi) Al Amediyah.” Subartu 2008 (2): 113–121 (in Arabic).

Mathiesen, Hans E. 1992. Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. 2 vols. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Miglus, Peter, Michael Brown, and Juan Aguilar. 2018. “Parthian Rock Reliefs from Amādiya in Iraqi-Kurdistan.” Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 11: 110–129.

Sykes, Mark. 1904. Dar-ul-Islam: A Record of a Journey through Ten of the Asiatic Provinces of Turkey. London: Bickers.