Images

VR Tour

Notes

History

While Rouen was the undisputed capital of ducal Normandy, Caen was the secondary center of ducal power developed by William the Conquerer as a new planned market town dominated by two great Benedictine monasteries, S-Etienne and La Trinité and a powerful castle. The Benedictine church of S-Etienne served as a mausoleum for William the Conquerer, while La Trinité was the resting place of his wife, Mathilde of Flanders. S-Etienne was the principal monastery of the duchy and guardian of the royal regalia -- a kind of Plantagenet S-Denis. William kept much of his Norman treasure in Caen and the Norman exchequer was based there. The importance of Caen declined?none of William the Conquerer's successors were buried there and Rouen continued to gain in importance, favored by its proximity to Paris. After the conquest of 1204 the Capetian kings made Rouen their capital. Yet S-Etienne of Caen remained well-endowed and prosperous, housing sixty monks in the mid-13th century

Date

Begun ca. 1060

Plan

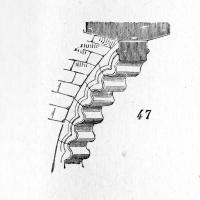

The aisled nave has eight bays organized into four double-units covered by sexpartite vaults (originally the nave had a wooden roof). The eight bays of the aisles, originally groin-vaulted now have quadripartite rib vaults. To the west is a twin-towered frontispiece and narthex. From the crossing is generated a projecting transept with galleries. The original chevet, possibly vaulted (groin vaults) had triple apses en echelon. The aisled chevet has four bays and is terminated by a 7-segment hemicycle surrounded by ambulatory and seven radiating chapels. The chapels are spatially linked, creating a distant reference to the chevet of S-Denis. Notable are the staircase turrets at the base of the outer envelope of the hemicycle -- turrets which continue up to form towerlets creating a dramatic jagged silhouette. The deeply projecting chapels that flank the chevet aisles are original.

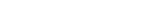

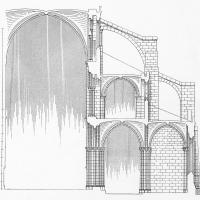

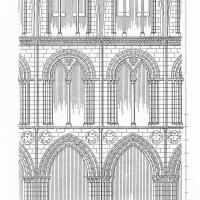

Elevation

A three-story, galleried elevation throughout. The three levels, arcade, gallery and clerestory have approximately equal heights. In the nave the main piers have a stepped, compound core, to which colonnettes are applied to provide visual support for the double order of the main arcade. The use of the curved roll or torus articulating the outer order of the arcade and demanding its own supporting colonnette is a most significant new element of articulation (Bernay had pioneered the centrally-placed torus in the choir arcade). The divisions between bays are marked by an applied colonnette that runs the entire height of the elevation; in every alternating support that colonnette projects from a projecting rectangular band or dosseret. This alternation anticipates the later installation of the sexpartite vaults. In the chevet, begun more than a century later, the builders have retained the three levels, but entirely changed the forms of articulation. In the straight bays the divisions are not articulated as strongly as in the nave; the very slender colonnettes in the arcade begin with corbels at the level of the abaci. The colonnettes are increased in thickness at gallery level. The compound piers have multiple skinny colonnettes corresponding to the multiple orders of the thick arcade. Deep oculi enliven the spandrels. The gallery openings where a single rounded arch encloses two sharply-pointed lancets, has a light, airy look The clerestory, with its triplets, has a passage and no tracery. Vaults are quadripartite. Sculptural forms very similar to those of Bayeux

Chronology

The church was begun around 1060; nave vault installed c.1120 (based on style of capitals which resemble royal donjon at Falaise: possible involvement of Henry I) Older scholarship dates the chevet as late as 1210 or 1220; recently Lindy Grant has proposed 1180s, with links to Fécamp, Eu, S-Denis, Notre-Dame of Paris and Vézelay. Very extensive restorations in the nineteenth century were directed by Ruprich-Robert.

Significance

This is one of the very few great churches housing the tomb of the master mason who built it: a tomb slab in the axial chapel commemorates Master William, petrorum summus in arte: "top rank in the art of masonry." Reference to Abbot Suger's shrine-chevet of S-Denis may be intended to express the role of this church as a mausoleum. Master William also makes clear references to the architectural forms of Notre-Dame of Paris, Mantes-la-Jolie and Canterbury Cathedral. The nave served as paradigms inspiring builders of subsequent generations particularly in England.

Location

Bibliography

Bayle, M., (ed) L'architecture normande au moyen âge, Caen, 1996

----, "La scultura," I Normanni. Popolo d'Europa 1030-1200, Ed. Mario d'Onofrio, 1994, 57-66

----, "Les ateliers de sculpture de Saint-Étienne de Caen au XIe au XIIe siècles," Anglo-Norman Studies, X: Proceedings of the Battle Conference, 1987, Ed. Allen Brown, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 1988, pp 1- 23

Bertaux, J.-J. et al, Caen, cité médiévale: bilan d?archéologie et d?histoire, Calvados, 1996 AA1046 C11 C68

----, "L'architettura religiosa," I Normanni. Popolo d'Europa 1030-1200, Ed. Mario d'Onofrio, 1994, pp 35-42

Burnouf, J., "Recherches archéologiques sur le site de Saint Étienne de Caen," Archéologie médiévale, vol. 13, 1983, pp 185-230

Carlson, Eric, The Abbey Church of Saint-Etienne at Caen in the Eleventh and Early-Twelfth Centuries, New Haven, 1969 AA398 C1 C19.

----, "Fouilles de Saint-Étienne Caen 1969," Archéologie médiévale, Vol. 2, 1972, pp 89-102

Coppola, G., "Carrières de pierre et techniques d?extraction: la pierre de Caen," in Baylé ed., 1977, 1, 289-303

----, "Notazioni su alcuni materiali e procedimenti construttivi," I Normanni. Popolo d'Europa 1030-1200, Ed. Mario d'Onofrio, 1994, pp 53-56

Gouhier, P., L'Abbaye aux Hommes, Saint-Étienne de Caen, Paris, 1960

Grant, L. "The Choir of Saint-Etienne at Caen," Medieval Architecture and Its Intellectual Context, Studies in Honor of Peter Kidson, London, 1990, 113-125

-----, Architecture and Society in Normandy, New Haven, 205, 52-54

Harbottle, G.; Holmes, L.L., "In the steps of William the Conqueror: neutron analysis of Caen stone," Archaeometry: The Bulletin of the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, Oxford University, Vol. 45:2, 2003, 199-220

Héliot, P., "L'ordre colossal et les ordres superposés de St-Etienne de Caen à Notre-Dame d'Amiens," Revue archéologique, 1960, 1-2

----, Saint-Étienne de Caen Saint Paul d'Issoire et les arcades murales dans l'architecture du Nord-Ouest de l'Europe, Cologne, 1959

Hippeau, C., L'abbaye de Saint- Étienne de Caen, 1066-1790, Caen, 1855

Lambert, E., "Caen roman et gothique," Bulletin de la société des antiquaires de Normandie, 43, 1935, 46

Mérindol, C. de, "De l'abbaye Saint-Étienne de Caen à l'église du couvent Saint-Nicolas-de-Tolentin à Brou. Réflexions sur les carreaux de pavement," Bulletin de la Société nationale des antiquaires de France, 2002, 79-92

Noell, M., Chor von Saint-Etienne in Caen: gotische Architektur in der Normandie unter den Plantagenet und die Bedeutung des Thomas-Becket-Kultes, Worms, 2000 AA452 C11 N68

Plant, R., "Ecclesiastical architecture, c. 1050 to c. 1200," A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World, Ed. Christopher Harper-Bill and Elizabeth van Houts, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2003, pp 215-253

Ruprich-Robert, V., L'église Ste-Trinité (ancienne Abbaye-aux dames) et l'église St-Étienne (ancienne abbaye-aux-hommes) à Caen, Caen, 1864

Serbat, L., "Caen, Eglise Saint-Etienne et abbaye aux hommes," Congrès archéologique, 75, 1908, 21.

Stöver, J., "Beschouwingen bij een "bouwschool": vorstelijke elementen aan elfde-eeuwse kerken in Normandië," Bouwen en duiden: Studies over architectuur en iconologie, Ed. E. den Hartog et al., Alphen aan den Rijn, 1994, pp 53-77

----, "Middeleeuwse kerkbouwkunst als betekenisdrager. Normanisch-vorstelijke elementen aan de kathedraal van Bayeux," Aanzet, vol. 8:3, 1990, pp 207-220

Tatton-Brown, T., ?La pierre de Caen en Angleterre,? in Baylé ed., 1977, 305-14