Images

VR Tour

Notes

Date

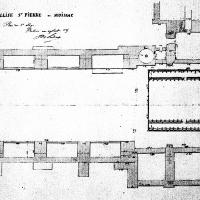

Begun ca. 11th century

Sculptural Program

The portal on the south side of the nave at St. Pierre at Moissac is a prototypical Romanesque eschatological portal of the type known as Maestas Domini. The lowest lintel displays a series of foliated motifs and rosettes, while the second register begins the display of the elders of the Apocalypse, seated and carrying musical instruments and chalices. The tympanum shows a fearsome Christ in Majesty, surrounded by the tetramorph, two angels, and two more registers of seated elders. The active, ecstatic poses of the elders contrasts powerfully with the solid, unmoving solemnity of Christ. The three bands of voussoirs are all foliate motifs.

The trumeau below is carved in relief on three sides. The front shows three pairs of lions, one distinctly male and one distinctly female, their bodies crossing diagonally and rhythmically. The right interior of the trumeau has a relief of Jeremiah, while the left has a relief of St. Paul, both of whom seem to balance gracefully on the cusped moldings of the entrance portals. The jamb reliefs on either side of the door are, on the left, Peter, and on the right, Isaiah.

The west wall of the porch shows a cycle of reliefs depicting the parable of Dives and Lazarus above, and the temptation of Avaritia and Luxuria below. The frieze above begins the story of Lazarus and Dives, with the depiction on the right-hand side of the feast of the wealthy man, Dives, seen seated behind a table at the center. To the left is shown Lazarus the beggar, lying prostrate with sores on his legs. An angel hovers above him. He has just died, and his soul is shown at the bosom of Abraham to the left of this scene. The outer figure, holding a scroll, is probably St. Luke, the author of the Lazarus parable. The upper arcade reliefs depict the continuation of the story. The interior scene shows Dives' funeral. The wealthy man is shown on his deathbed, surrounded by hovering demons, two of whom rip his soul from his mouth. The outer relief shows the torment of Dives' soul in Hell. This parable illustrates the sins of pride and avarice. The lower arcade reliefs depict, on the interior, a wrinkled and emaciated woman with serpents at her breasts and a distorted, bloated demon who grabs her arm. These two figures allegorically symbolize the sin of luxuria, or lust. The outer relief, much damaged, depicts a wealthy man weighed down with sacs of money and a demon on his shoulder, and a poor, hunched beggar who approaches the rich man to ask for money. This pairing symbolizes another sin, that of avaritia (avarice).

The east wall of the porch displays scenes from the Infancy of Christ. The narrative begins on the interior lower arcade with the Annunciation, followed by the Visitation on the exterior lower arcade. The second register of the arcade shows the Adoration of the Magi, with the Christ Child and Holy Family contained in the outer arcade, and the three Magi with their gifts on the inner arcade. The star that led the Magi is depicted above the head of the Christ Child. The story continues in the frieze above with, from exterior to interior, the Presentation in the Temple and Purification of the Virgin, the Dream of Joseph and the Flight into Egypt, and the apocryphal story of the Fall of the Egyptian Idols.

St. Pierre at Moissac is also known for the many historiated capitals and figural slab reliefs of its cloister. The cloister reliefs were probably created under the tenure of abbot Anquêtil, who ran the monastery around the turn of the twelfth century. The porch sculptures were probably created in the era after his death under Abbot Roger, around 1120-1125, though this is widely debated. As a whole program, the three cycles of the porch fit together in interesting ways. The Christ in Majesty of the central tympanum illustrates a "present eschatology," which refers to Christ's eternal seat of judgment and power outside of time through the Church. The figure of Christ in Majesty and the surrounding tetramorphs probably drew its composition from Carolingian models, such as at Dufay, which dates from the ninth century. There are also many parallels to Carolingian manuscript illumination. The Incarnation cycle can be seen as a counterpart to Christ in Majesty on the tympanum, a description of his first arrival on earth which alludes to his eternal and continuing presence. The inclusion of the parable of Dives and Lazarus, and the condemnation of the sins of pride, lust and avarice are debated in the overall program. We can see their inclusion in conjunction with the terrifying power of Christ at the Second Coming; beware the three great sins of pride, avarice and lust lest you be judged and punished at the end of time. These sins were especially dangerous to the monk, and thus their condemnation in a monastic context is logical. Additionally, the contrast in fates of the two men refers to the notion of judgment and the power of Christ to determine the saved and the damned.

Location

Bibliography

Alauzier, L. d', "La pierre Constantine et le linteau du porche de l'abbatiale de Moissac," Bulletin de la Société des études littéraires, scientifiques et artistiques du Lot, vol. 105:1, 1984, pp 9-10

Barral Altet, X., "La mosaïque de pavement médiévale de l'église de Moissac," Bulletin de la société nationale des antiquaires de France, 1975, pp 72-73

Cattin, E.; Durliat, M., L'abbaye de Moissac, Rennes, 1996

Dixon, S. R., The power of the gate: the sculptured portal of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, Ithaca, 1987

Droste, T., Die Skulpturen con Moissac: Gestalt und Funktion romanischer Bauplastik, München, 1996

Forsyth, I. H., "Narrative at Moissac: Schapiro's legacy," Gesta, vol. 41:1, 2002, pp 71-93

Fraïsse, C., "Le cloître de Moissac: a-t-il un programme?" Cahiers de civilization médiévale, Xe-XIIe siècles, vol. 50:199, 2007, pp 245-270

----, Moissac: histoire d'une abbaye: mille ans de vie bénédictine, Flaujac-Poujols, 2006

Joergensen, B., "La composition du Tympan de Moissac expliquée par une projection panoramique," Cahiers de civilization médiévale, Xe-XIIe siècles, vol. 15:60, 1972, pp 303-308

Klein, P. K., "Topographie, fonctions, et programmes iconographiques des cloîtres: la galerie attenante à l'église," Der mittelalterliche Kreuzgang. Architektur, Funktion und Programm, Ed. Peter Klein, Regensburg, 2004, pp 105-156

----, "Programmes eschatologiques, function et reception historique des portails du XIIe s.: Moissac-Beaulieu-Saint-Denis," Cahier de civilization médiévale, Xe-XIIe siècles, vol. 33:132, 1990, pp 317-349

Kline, R. M. C., The decorated imposts of the Cloister of Moissac, Los Angeles, 1977

Méras, M., L'art roman à Moissac: IXe centenaire de l'abbaye, 1063-1963, 1963?

Mérindol, C. de, "Le cloître de Moissac: Trois enquêtes distributionelles," Académie des Inscriptions et belles-lettre. Comptes-rendus des séances, vol. 4, 2009, pp 1689-1751

Mezoughi, N., "Le tympan de Moissac etudes d'iconographie," Cahiers de Saint-Michel-de-Cuxà, vol. 9, 1978, pp 171-200

Möbius, H., "Französische Bauplastik um 1100. Form und Funktion im geschichtlichen Prozess," Skulptur des Mittelalters. Funktion und Gestalt, Ed. Friedrich Möbius und Ernst Schubert, Weimar, 1987, pp 44-80

Pereira, M. C. C. L., "Syntaxe et place des images dans le cloître de Moissac. L'aporte des méthodes graphiques," Der mittelalterliche Kreuzgang. Architektur, Funktion und Programm, Ed. Peter Klein, Regensburg, 2004, pp212-219

Rutchick, L., "Visual memory and historiated sculpture in the Moissac cloister," Der mittelalterliche Kreuzgang. Architektur, Funktion und Programm, Ed. Peter Klein, Regensburg, 2004, pp 190-211

Schapiro, M., The Romanesque Sculpture of Moissac, New York, 1931

Skubiszewski, P., "Le trumeau et le linteau de Moissac un cas du symbolism médiéval," Cahier archéologiques: fin de l'antiquité et moyen âge, vol. 40, 1992, pp 51-90

Talbot, M. O., "St. Pierre-de-Moissac portal and its Solomonic guardians," Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, vol. 27, 1996, pp 81-98

Tcherikover, A., "The fall of Nebuchadnezzar in Romanesque sculpture, Airvault, Moissac, Bourg-Argental, Foussais," Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 49:3, 1986, pp 299-300

Ugaglia, E., "Fouilles sous le porche de l'abbaye de Moissac (Tarn-et-Garonne)," Histoire et archeology. Les dossiers, vol. 120:7, 1987, pp 100-101

Vidal, M., "Le tympan du portail de Moissac," Cahiers de Saint-Michel-de-Cuxà, vol. 2, 1971, pp 89-97

----, "Le portail de Moissac et son rayonnement en Bas-Limousin," Centre international d'études romanes: Revue trimestriel, 1970, pp 64-71

----, "L'art du VIIe au IXe siècle à Moissac," Bulletin de la Société archéologique de Tarn-et-Garonne, vol. 95, 1970, pp 9-18

Voinchet, B., "L'abbatiale Saint-Pierre de Moissac," Monuments historiques de la France, vol. 181, 1992, pp 97-99

----, "Le portail de Moissac," Monuments historiques de la France, vol. 4, 1976, pp 20-25

Yvonnet-Nouviale, V., "A propos de neuf chaiteaux de Saint-Caprais d'Angen: influences croisées, Toulouse et Moissac," Mémoires de la Société archéologique du Midi de la France, vol. 59, 1999, pp 57-71