Images

VR Tour

Notes

History

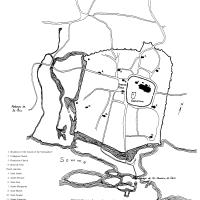

The city of St-Quentin has been associated with the Roman town of Augusta Viromanduorum, although the exact location and nature of the Roman settlement remain unclear. The modern city and church derive their name from an Early Christian missionary, Quentin, martyred in the late third century according to legend. His body was said to have been discovered several decades later by a Roman widow, Eusebia, in the marshes of the Somme River at the edge of modern Saint-Quentin. Eusebia buried the martyr's remains at the top of the hill and built a small shrine. Recent excavations around the church's crypt have in fact uncovered the remains of a building of this date. Gregory of Tours listed the chapel as a pilgrimage site, and the precise location of the tomb was rediscovered by Saint Eloi, Bishop of Noyon, in the 7th century "under the pavement of the basilica". Eloi is said to have enlarged the church, and the remains of a 7th-century floor in the area near the crypt have also recently been verified. St-Quentin has also laid claim to preceding Noyon as the region's episcopal see, and texts suggest that in the early Middle Ages it was a double church foundation -- one church centered around Quentin's pilgrimage, and the other dedicated to the Virgin. St-Quentin flourished as a monastery and pilgrimage site under the Carolingians, and fragments of walls from this period have also been identified by archaeologists. The monastery was probably damaged during the invasions of the late 9th century, and flourished again in the later 10th century with the Counts of Vermandois as patrons. Historical annals describe a rebuilding in the mid-10th century. It was probably at this time that the former monastery was transformed into a foundation of secular canons, a process repeated at several other sites in the region, including St-Fursy of Péronne. The church again suffered some damage during the local ducal wars in , but nothing is known of the extent of the damage or its repair. 17th- and 18th-century antiquarians credited Count Raoul of Vermandois (ca. 1100-1152) with rebuilding the church at that time, but the document on which this is based is an obituary gift, more reasonably dated to the time of the Count's death some 50 years later. Documents that may be associated with the construction of the Gothic church include the obituary of treasurer Matthew Le Sot, who died by 1197, and is credited with "laying the first stone", and series of chapel foundations, wills, and obits that can be dated to about 1195-1205. The relics of Quentin and two other patron saints, Victoric of Amiens and Cassian of Auxerre, were translated from the old crypt (to the east of the main crossing) to a temporary location in the nave in 1228. They were translated into the new choir in the presence of Louis IX in 1257.

Date

Begun ca. 1200

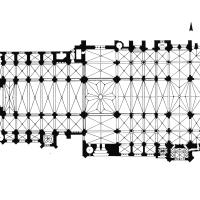

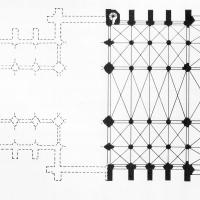

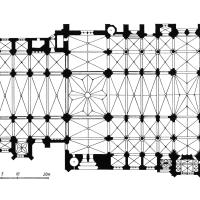

Plan

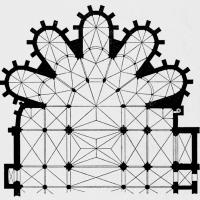

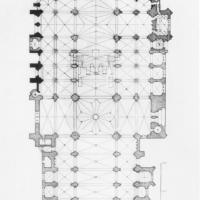

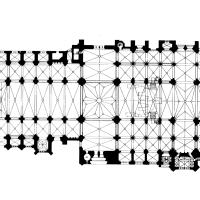

An aisled basilica church intercepted by two transepts with a great western central tower. The unusually short chevet is ringed by an ambulatory formed of five exedrae opening into five generously-projecting chapels. Two slender columns in each chapel opening create a screen-like effect that might be compared with Saint-Remi of Reims, Notre-Dame-en-Vaux in Châlons-en-Champagne and Auxerre Cathedral. The arrangement of the ambulatory with its clerestory windows has led some historians to link this church with Bourges and Beauvais Cathedrals.

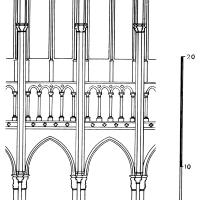

Elevation

The floor of the upper chapel in the western tower which is open to the main vessel (an arrangement reminiscent of the Carolingian Westwerk) is lower than the nave triforium, . The chevet includes radiating chapels are lower than the ambulatory vault; the ambulatory is equipped with clerestory windows above the chapel entrances, similar to Beauvais Cathedral. This arrangement creates the appearance of a four-story elevation through the hemicycle. The three-story elevation of the main vessel is otherwise consistent throughout chevet, transepts and nave despite multiple hiatuses in construction. The clerestory windows are approximately equal in height to the main arcade, but an unusual extension of unarticulated wall between the triforium and clerestory sill makes the clerestory seem more attenuated. The total height from the top of the triforium to the high vaults is inconsistent with the proportional relationships of the lower stories, suggesting that the intended height of the clerestory was increased during construction, bringing the total height of the interior to 34.5m.

Chronology

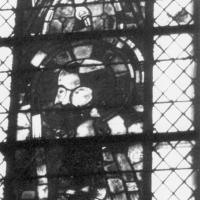

The early history of construction at Saint-Quentin has been recently revealed through archaeology. Roughly in the position below the altar, sarcophagi, mosaics and evidence of building construction has been unearthed dating from the 4th, 7th and 9th-centuries. The existing building is difficult to determine a specific date. The western tower is thought to date from the 11th to the 12th centuries. The interior of the narthex appears to have been remodeled in the mid-to-late 12th century, while the pier construction, dado profiles and capitals of the upper chapel in the west tower appear to immediately precede the construction of the radiating chapels. Construction of the Gothic chevet began at the east end in the late twelfth century. Documented chapel foundations and the image of a named donor in the stained glass suggest a date in the 1190s. Work proceeded in multiple campaigns from east to west with the nave completed in the fourteenth century. The south arm of the eastern chapel, in danger of collapse, was replaced in the late 15th century and has been considered a masterpiece of Flambouyant. In the late middle ages consolidation work focused upon the western transept arms.

Significance

The former collegiate church of S-Quentin bridges the transition between late-12th-century traditions of Champagne and Picardy and the development of High Gothic froms that saw their first complete statement in Chartres Cathedral. The articulation of the ambulatory and radiating chapels indicate connections to several lat-12th century buildings in Champagne and Picardy (S-Remi of Reims; Châlon-en-Champagne) while the lower stories of the chevet compare with Soissons and Chartres. Unusual beaked capitals in the radiating chapels and slender en-délit shafts throughout seem to anticipate Rayonnant. As work continued into the upper chevet the builders continued to employ the latest innovations, including bar tracery in the hemicycle clerestory and north transept rose and openwork flying buttresses comparable to those of Troyes and Amiens Cathedrals. The choir was consecrated in 1257. (Ellen Shortell)

Location

Bibliography

Bénard, E., Collégiale de Saint-Quentin, Paris, 1867.

F. Bucher, "An Unknown Gothic Drawing from Saint-Quentin," Gesta, XXVI, 1987, 151-152.

Deneux, "Saint-Quentin," Bull mon., 1925

Héliot,, La basilique de Saint-Quentin et l'architecture du Moyen Age, Paris, Picard, 1967. review Brandenburg, Bull mon 128, 1970, 159

E. Shortell, E., "Dismembering Saint-Quentin: Gothic Architecture and the Display of Relics," Gesta, 36, 1996, 32-47