Images

VR Tour

Notes

History

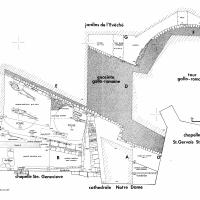

A Roman city on the site was enclosed inside oval walls. Early Christianity associated with the mission and cult of Saint Rieul whose shrine was outside the Roman wall. Notre-Dame of Senlis replaced S-Rieul as principal church, becoming a cathedral at a date probably at the end of the 10th century when the 7th-century church on the site was replaced under bishop Eudes I (986-995). The county of Senlis was attached to the royal domaine in 987 under Hugues Capet: this was a principal residence of Capetian kings who were responsible for the foundation of several ecclesiastical institutions in the city including the collegiate church of S-Frambourg and the abbey of S-Vincent. In the 12th century Senlis was considered a royal city of the same rank as Paris, Pontoise, Poissy and Compiègne. The construction of the Gothic cathedral is associated with the initiative of Bishop Thibaut, elected in 1151 and the support of King Louis VII--Thibaut was a close associate of Abbot Suger of S-Denis. Construction work was continued by Bishop Amaury (1156-1167), Henri (1169-1185) and completed by Geoffrey (1169-1185) under whom the dedication took place.

Date

Begun ca. 1151

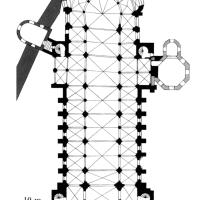

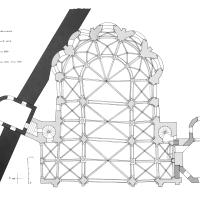

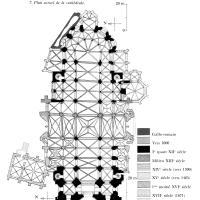

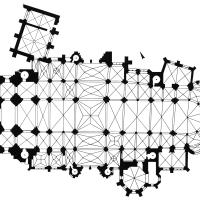

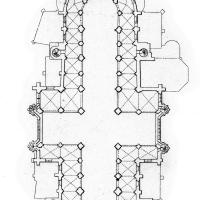

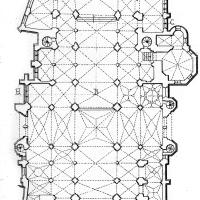

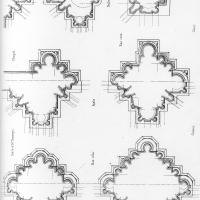

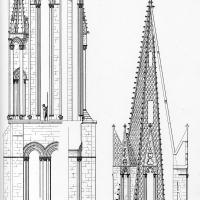

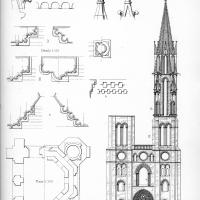

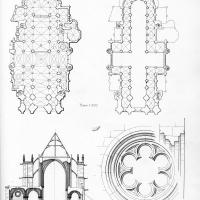

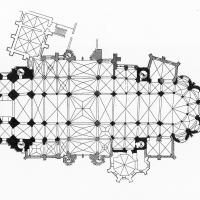

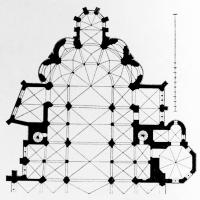

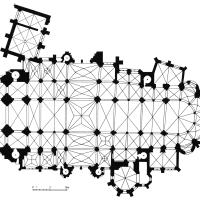

Plan

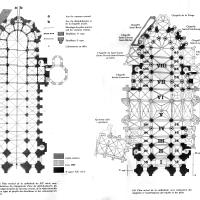

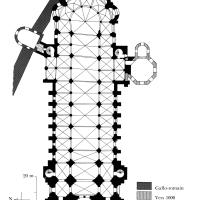

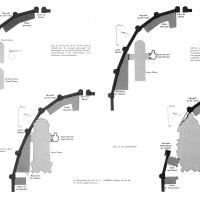

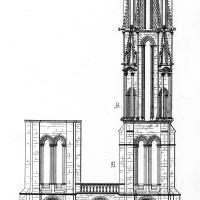

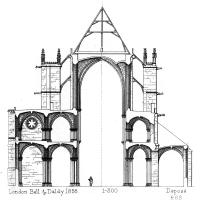

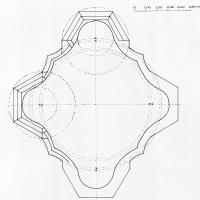

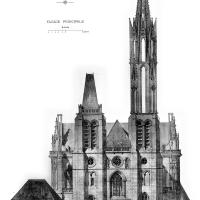

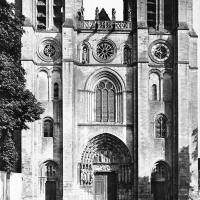

An aisled basilica with sexpartite vaults over alternating supports; originally there was no transept. The transept was added between the 13th and 16th centuries. The chevet is a five-segment hemicycle with ambulatory and shallow radiating chapels with a deeply projecting (added) axial chapel. The harmonious western frontispiece has two towers. The cathedral was heavily damaged in 1504 after which the entire clerestory was rebuilt.

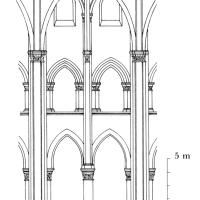

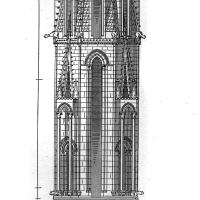

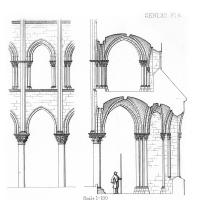

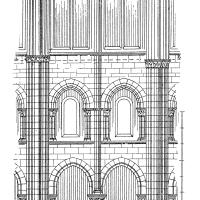

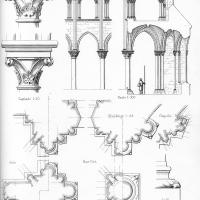

Elevation

The building has a three-story elevation of arcade, vaulted gallery and originally had a small clerestory which was enlarged in the 16th century.

Chronology

Circa 1150 is normally assigned as the starting date for Senlis. The sculptural portal dates to the 1160-1170's.

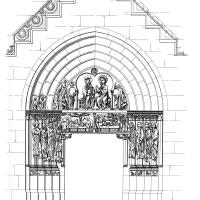

Sculptural Program

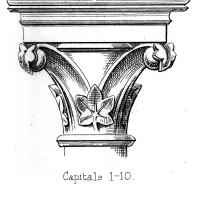

The single sculpted portal at Senlis marks experimentation with a new style and subject-matter in the late 1160s in the Ile-de-France region. The portal centers around the Coronation of the Virgin. The lintel depicts a scene of the Dormition of the Virgin on the left and the Assumption of the Virgin on the right, separated by a slender colonnette. The tympanum above shows The Virgin Mary and Christ enthroned side by side under a swooping canopy. They are flanked by angels with tapers and censers. The first three bands of voussoirs show the Tree of Jesse, while the outer band shows Old Testament patriarchs and prophets. The jamb figures were much remodeled in the 19th century, and show on the left, from exterior to interior, John the Baptist, Samuel or Aaron, Moses, and Abraham. The right side, from interior to exterior, shows Simeon, Jeremiah, Jacob, and David. The trumeau is now lost, but would have shown Saint Rieul, the first bishop of Senlis.

Stylistically, the portal at Senlis marks a dramatic change in the articulation of gesture, pose, and drapery. Paul Williamson attributes this change to an increasing examination of smaller objects in metal. These cast and molded objects achieved a greater fluidity of pose and drapery, which he argues sculptors then attempted to reproduce in their own medium. Certainly, the twisting, graceful poses of the figures in the Tree of Jesse, and the whirling, gathered folds of Christ's robe recall the goldsmith's work. These figures seem to flow freely from the confines of their architectural setting. The subject matter, too, shows a great shift from prior paradigms. The Coronation of the Virgin, a theme taken from the Song of Songs and popularized by late twelfth-century figures such as Abbot Suger, Bernard of Clairvaux, and St. Anselm, moved away from previous terrifying scenes of eschatological destruction towards an emphasis on the human, approachable, forgiving aspect of the Church through the figure of the Virgin. Seen as the Bride of Christ, his queen in Heaven, she acts as the bond between the Church and Christ's suffering. She is seen as a maternal, nurturing figure who, through her intimate relationship with Christ, could intercede on behalf of the worshipper. The portal at Senlis is the earliest instance of this shift in rhetorical imagery, attempting to recast the Church in a forgiving, approachable light. From the workshops at Senlis, this type of program spread throughout the Ile-de-France and beyond.

Significance

It is hard to separate the construction of Senlis cathedral from the growing power of the Capetian monarchs, Louis VI and VII. The western portal (1160s-1170s) , a depiction of the Coronation of the Virgin, is the earliest surviving monumental expression of the new fervent Gothic spirit based on the Song of Songs. Supple dampfold drapery and animated bodies associated with the 'Antique Revival' mode. This portal is located directly outside and facing the royal palace. The galleried ('royal') elevation has importance as prototypes for the builders of Notre-Dame of Paris. The western frontispiece refers to Saint-Denis.

Location

Bibliography

Senlis : Un moment de la sculpture gothique : Exposition. Senlis: Association pour la sauvegarde de Senlis, 1977.

Adams, Roger J. "Isaiah or Jacob? The Iconographic Question on the Coronation Portals of Senlis, Chartres and Reims." Gesta, XXIII, no. 2 (1984): 119-30.

Aubert, Marcel, Monographie de la cathédrale de Senlis, Senlis,: Dufresne, 1910.

-- -- -- . Senlis, Paris,: H. Laurens, 1912.

Bos, Agnes, and Delphine Christophe. "L'aménagement liturgique du sanctuaire dans les cathédrales médiévales : les autels "de retro"." Patrimoines, no. 2 (2006): 76-81.

Brouillette, Diane Cynthia. "The Early Gothic Sculpture of Senlis Cathedral." 1981.

Comité archéologique de Senlis., and Société d'histoire et d'archéologie de Senlis. "Comptes Rendus Et Mémoires." v. Senlis, France: Comité archéologique de Senlis, 1862.

Crepin-Leblond, Thierry, and C. Dubois. "Une tête inédite provenant des voussures du portail occidental de la cathédrale de Senlis." Bulletin Monumental, 151, no. 2 (1994): 428-29.

Kasarska, Iliana, and Anne Lombard-Jourdan. "Politique royale et sculpture monumentale à Paris au Xiie siècle." Bulletin Monumental, 157, no. 4 (1999): 385-86.

Leblanc, Henri Charles. Senlis, Senlis: H. Leblanc, 1955.

Meunier, Florian. "Les cathédrales flamboyantes de Martin de Pierre Chambiges." Revue de l'Art, 138 (2002): 31-42.

Paulet Renault, Gilberte. Châalis, Son Abbaye Cistercienne, Les Cardinaux D'este, Les Stalles De Baron, Le Maître Autel De Senlis, Les Collections Jacquemart André : La Mer De Sable, Paris: Editions du Cadran, 1962.

Pernoud, Régine, Charles Waldschmidt, Pierre Kjelleberg, Maurice Berry, and Philippe Seydoux. "Picardie." Monuments historiques de la France, 4 (1975).

Plagnieux, Philippe. "L'abbatiale de Saint-Germain-des-Prés et les débuts de l'architecture gothique." Bulletin Monumental, 158 (2000).

Sandron, Dany, and Florian Meunier. "Martin et Pierre Chambiges à Senlis." Bulletin Monumental, 161, no. 3 (2003): 260.

Steyaert, Delphine, and Sylvie Demailly. "Notre-Dame de Senlis." In La couleur et la pierre : polychromie des portails gothiques : Actes du colloque : 12-14 Octobre 2000, 105-14. Paris: Picard, 2002.

Thérel, Marie-Louise. Le triomphe de la Vierge-Église : à L'origine du décor du portail occidental de Notre-Dame de Senlis : sources historiques, littéraires et iconographiques, Paris: Editions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1984.

Verdier, Philippe, Le couronnement de la Vierge; les origines et les premiers développements d'un thème iconographique,* Montreal: Institut d'études médiévales, 1980.Vermand, Dominique. *La cathédrale Notre-Dame de Senlis au Xiie siècle : Étude historique et monumentale, Senlis: Société d'histoire et d' archéologie de Senlis, 1987.

Vermand, Dominique, and Sandrine Platerier-Formentin. La cathédrale Notre-Dame de Senlis : Oise, Vol. 142, Itinéraires du patrimoine. Amiens: AGIR-Pic, 19